Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

Cuba, beaches, the mysteries of marriage: a retrospective of the late director’s films.

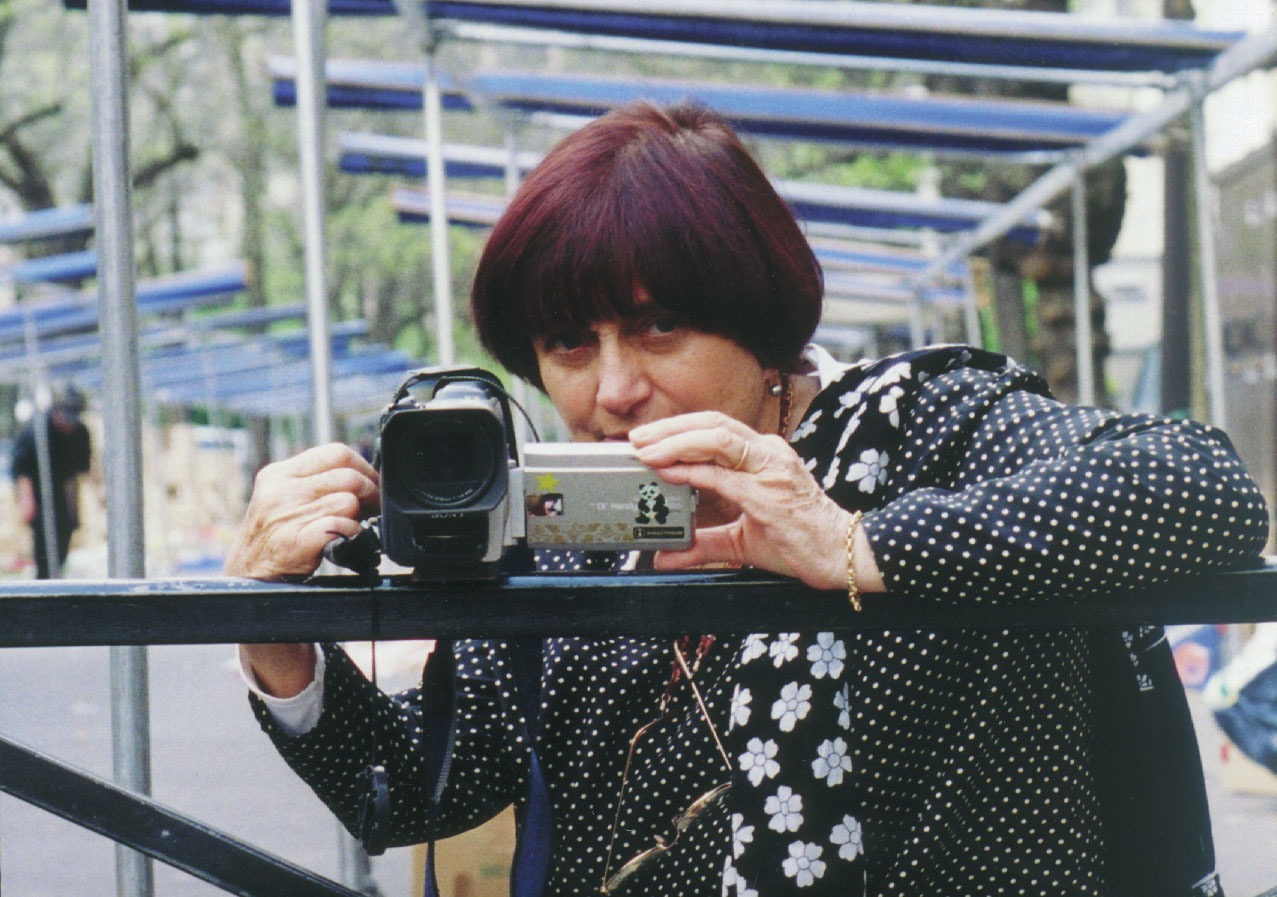

The Gleaners and I. Image courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

“Varda: A Retrospective,” Film at Lincoln Center, New York City, through January 6, 2020

• • •

Something unexpected happened to Agnès Varda this century: the Belgian-born director, who died at the age of ninety in March, became a “treasure.” Her films, which include the features La pointe courte (1955), Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), and Vagabond (1985), received a fraction of the critical attention of those by her Nouvelle Vague peers. Was it because many of them were shorts? Because she often switched between fiction and nonfiction? Because she was a woman? It took the word-of-mouth success of The Gleaners and I (2000) for her reputation to swell. A wise, ludic, self-reflexive meditation on the ethics of waste, the documentary was made on a tiny budget, used a then-unfashionable digital camera, and was funny rather than ponderous (the default mode of many essay films).

La pointe courte. Image courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

Varda’s sensibility, her independence, her openness: these all spoke to younger artists and curators at least as much as they did to the film world. She started to be inundated with gallery commissions, appeared on tote bags and on the cover of lifestyle journals. Her distinctive look—a sly nun with hair that resembled avant-garde crème brûlée—helped make her an icon, a cuddlier Yayoi Kusama. A life-size cardboard cutout, produced by London’s BFI Southbank for a 2018 retrospective, drew lines of Instagramming tourists. It was hard not to feel this belated spotlight was distorting, that Varda was being defanged and patronized.

Black Panthers. Image courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

All the more reason, then, to celebrate Film at Lincoln Center’s career-spanning retrospective of Varda’s work, not least because it includes her earlier and rarely screened short films (on topics such as the Black Panthers), which display her prickly intelligence and political antennae. One of the best is Along the Coast (1958), a precursor of sorts to her final feature, Varda by Agnès (2019), in which she would claim, “If we opened people, we’d find landscapes. If we opened me, we’d find beaches.” Along the Coast is a portrait, both topographic and dreamy, of the Côte d’Azur and the Riviera, of the sunny Mediterranean that was increasingly colonized by migrants (white ones from Northern Europe).

Varda is already aware that looking—and photographing—involves power. She announces: “We’re not going to film the natives. In the popular imagination they’re always old and charming.” Instead, she focuses on tourists and travelers, evoking their disfiguring presence on the ancient shores through the use of angular shots and garish close-ups. Already too she’s directing as well as capturing reality; at one point she has a plastic toy seal sliver across a sunbathing body. At first Along the Coast glows with the Technicolor brightness of a sword-and-sandals epic or early teensploitation flicks, but Varda gradually infuses it with twilight pensivity—mulling about the “end of the party, end of the summertime,” highlighting the “abandoned gardens and forgotten villas” that she says “are cinema,” and pausing at a stretch of the beach that is shingled and strewn with flotsam. This, whatever vacationers may wish to believe, is no Eden.

Varda by Agnès. Image courtesy Film at Lincoln Center.

Varda traveled widely as a young woman—to Russia, China, Cuba. Salut les Cubains (1963) is a thinking-aloud about the last of those countries, from which, she says, “I brought back jumbled images. To order them, I made this homage.” That word homage may suggest the obsequious hagiographies often produced about Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. After all, as the voice-over declares, in the popular imagination “Cuba was a cigar-shaped island for men.” She subtly undermines that macho vision. “Beards are now everywhere,” she points out—sported by rebels, artists, government officials—but they’re most evident in a sugary form: the beard-like cotton candy that islanders like to devour.

Salut les Cubains is made up entirely of still photographs that home in on things most outsiders (or insiders, for that matter) wouldn’t spot: the tightness with which a young female student grips her pencil, the hand that men place on the shoulders of their women partners as they peer at exhibition images of the revolution. The photographs, sometimes edited into flip-book-style sequences, are often kinetic and joyful; revolution, for Varda as for Emma Goldman, is less about tub-thumping oratory and five-year-plans as it is about rhythm and exuberance, about transforming drudgery into dance.

There’s no formal analysis or totalizing theory in Salut les Cubains; Varda prefers notes, phrases, lyrical observations. She deploys two voices, male and female, to create a feeling of conversation and dialogue rather than professorial disquisition. She also offers snapshots of Cubans—among them novelist Alejo Carpentier, a museum cleaner, filmmaker Sara Gómez, architect Selma Diaz, singer Benny Moré—to support her proposition: any radical society needs polyphony and art (and art as polyphony) if it hopes to stay healthy.

Jacquot de Nantes. Image courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

Varda’s films were long overshadowed by those of her husband, Jacques Demy, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990. He directed the universally beloved musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and was the subject of her Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and The World of Jacques Demy (1995). The mysteries of a marriage, especially between artists, are central to Elsa la rose (1966), Varda’s riveting exploration of the relationship between the French surrealist and Communist Party member Louis Aragon and Russian-born poet and translator Elsa Triolet.

This twenty-minute work begins with a shot of him writing—and repeating with mounting intensity—the line, “I’m filled with the deafening silence of loving.” We hear his poetry about her. We hear him claim her as his muse. It’s wonderful, a barrage, too much. We see her in old photos, in close-up. She’s beautiful (and more so the older she gets). She also looks—what? Pleased? Embarrassed? Inscrutable? “I’m always thinking that Elsa is eluding me,” he says. “Yet I’ve been thinking this for the past thirty-seven . . . thirty-eight years.” (After she died in 1970, he came out as bisexual.) Documentary portraiture, reenactment, poetic incantation: the film is unstable, twinkling with possibilities, full of reverie and reflection.

Varda asks Triolet if Aragon’s poetry makes her feel loved. “Not the poetry! It’s the rest. Life. Writing a life story, with its stops, switches, signals, bridges, tunnels, catastrophes . . .” Varda’s own films, already by the mid-1960s, fashioned a singular poetry out of their curiosity and sharpness, their passion for individuals but also for friendship and solidarity, their awareness of aging and catastrophe—and their belief that we should skip, leap, and cha-cha-cha in the face of such sadness. God, how I miss her.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.