Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

Poetic parables: the Signature Theatre mounts Suzan-Lori Parks’s takes on The Scarlet Letter.

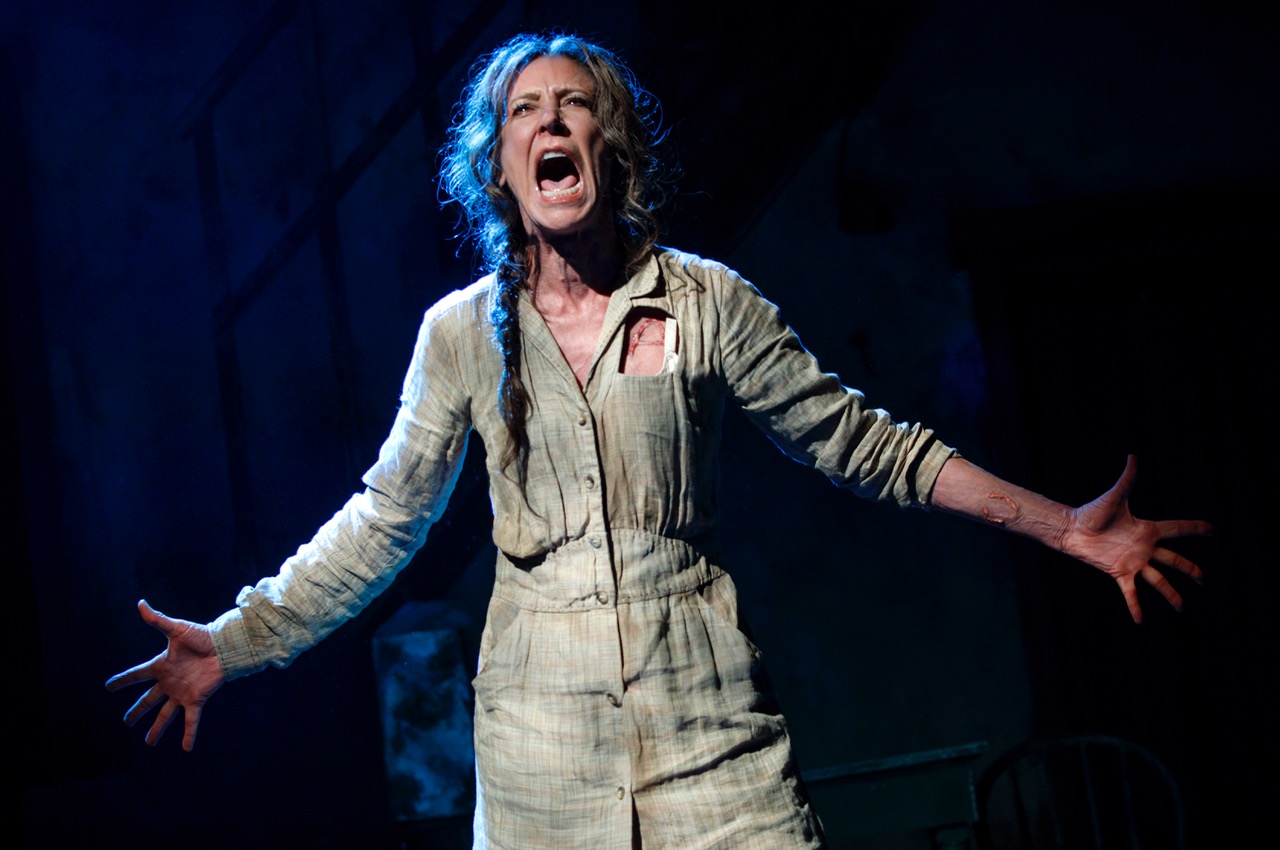

Christine Lahti in Fucking A. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The Red Letter Plays: Fucking A and In the Blood, by Suzan-Lori Parks, the Signature Theatre, 480 West Forty-Second Street, through October 8, 2017 (Fucking A) and October 15, 2017 (In the Blood)

• • •

It’s such a natural gesture to program Suzan-Lori Parks’s partner-plays In the Blood and Fucking A together, it makes you wonder—why has no other theater done this yet? The pieces were born from the same mother-thought: each is what Parks calls a “riff” on Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (she wrote one while trying to break through writer’s block on the other). They both revolve around a “fallen” woman named Hester; they’re both terrifying.

Parks has slowly, in her astonishing thirty-year career, percolated into the mainstream. She started in the late 1980s writing avant-garde head-trips like Imperceptible Mutabilities in the Third Kingdom (1989), reached the pinnacle of critical acclaim with jazz-inflected allegories like Topdog/Underdog (2001), then—after winning the Pulitzer for that play—swept closer to an almost conventional theatrical style. These days her mode is fable-tinted realism: her Father Comes Home from the Wars (2014) is hugely accessible by the standards of her early work. In the Blood and Fucking A, though, come from that golden middle age—written in 1999 and 2000 respectively—when she was just shifting away from the radical disorientations of her first masterpieces and starting to look to Brecht. Because of this, they manage to be both wildly poetic and as diamond-clear as parables. Using Brecht’s epic form, Parks has characters turn constantly outward to explain themselves, so there’s no doubt about what she wants us to feel or think. In In the Blood, six monologue “confessions” interrupt the action; in Fucking A, she includes Weill-esque musical numbers like “Working Woman’s Song” and the jailbird lament “The Making of a Monster.” Each play bangs out its moral emphasis, like a woman with a drum.

The Signature Theatre has selected Parks as one of their Residency One playwrights, so in the last two seasons they’ve also mounted her furious theatrical lyric The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World (1990) and Venus (1996), another feminist bruiser from her Brechtian period. This time, however, the Signature has programmed the Red Letter Plays simultaneously in two of the complex’s theaters, which sets up a frightening resonance in the building. The productions aren’t perfect; both ensembles need more velocity, and miscasting hampers Fucking A. But they’re synergetic. While you might slip out of one with some illusions about the world intact—the other is waiting a few feet away, ready to smash them with a hammer. As a pair, they work you over. Grief cop, rage cop.

The cast of In the Blood. Photo: Joan Marcus.

In the Blood is the stronger performance of the two, thanks to its cast and director Sarah Benson’s keen grasp of Parks’s killingly dry humor. Benson and set designer Louisa Thompson imagine the setting under a highway bridge as an immense, garbage-strewn quarter-pipe; it’s the skids as skateboarder’s playground. Hester La Negrita (Saycon Sengbloh) tries to make a home from the trash—a chute keeps dumping more onstage—and she scrapes by with her five “treasures”: her illegitimate children who adore her, pester her, and try to teach her the alphabet. So far, though, Hester knows only one letter. This she scrawls on the wall, her chalk “A”s wobbling along below the place where someone has spray-painted the word “SLUT.” The play’s efficient: when Hester’s precocious son Jabber (Michael Braun) finally tells her what the graffiti says, it breaks her mind and ends the play. Parks once said in an interview, “Words are charms. Spelling is like a magic.” So: Jabber says “slut,” the word-of-power is spoken—and shazam! It’s the end of Hester’s illusions.

Russell G. Jones and Saycon Sengbloh in In the Blood. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The wall is also Hester’s children’s playground—“extreme” action choreographer Elizabeth Streb has taught the actors to slide down it, fling themselves against it, run up it till they’re nearly flying. Adult actors play Hester’s children, and they also double as the “helpful” grown-ups that tempt and torment her: Welfare (the hilarious Jocelyn Bioh), deadbeat Reverend D (Russell G. Jones), Hester’s awful friend La Amiga Blanca (Ana Reeder), and a quack Doctor (Frank Wood). The play gets its energies—huge, volcanic ones you should feel under your feet—by doggedly degrading Hester. Everyone’s always holding out promises to her and then snatching them away. Sengbloh plays her sweetly; Hester’s expression stays innocent as the world’s foot comes down on her neck. She always answers “yes” when people ask her for help or love or sex, and when they inevitably crucify her, we realize we’re watching Parks’s Passion play—one where the Christ figure just . . . stays forsaken.

Brandon Victor Dixon and Christine Lahti in Fucking A. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Across the Signature lobby, director Jo Bonney’s production of Fucking A isn’t calling on the same deep powers, though the play itself is still superb. Built as a kind of nightmarish folktale, Fucking A makes its Hester (Christine Lahti) wear her “A” as a literal brand. Seared into the flesh of her shoulder, this is her badge of office: Hester is the abortionist for her tiny, strange, Grimm-dark little village. All her earnings go to buy her son Boy (Brandon Victor Dixon) out of his incarceration in a scarily recognizable corporation-cum-prison (“Freedom isn’t free!” chirps a bursar-cum-parole officer), but the system’s stacked against her. Boy himself now goes by Monster—thirty years inside for some stolen meat has burnt up his goodness. So Hester, her apron stained with blood, starts to wreak vengeance on those who put him there.

There are some fine performances among the company, like Marc Kudisch as the town Mayor and Raphael Nash Thompson as a lovable Butcher. But the production is just too lethargic. The songs, written by Parks and played by the multi-talented ensemble, unfold at a dirge pace. The plot—full of mistaken identities and accidental revenges—needs speed to make sense; the play’s fanged, but the jaws are closing awful slow. And what is Christine Lahti doing here? Onscreen, Lahti’s gift is her laser-fine control, but onstage this style makes her seem expressionless. Worse, it’s catching, so actors in scenes with her dial down the play’s wild carnival. Yet still, the script survives, and thanks to Parks’s innovative structure, the audience sort of winds up reading it while watching it: she has invented a language called Talk, spoken among the women, which the production has to supertitle. (As in In the Blood, Parks is literally putting the writing on the wall.) And isn’t it interesting that all the unspeakable stuff in this awful little olden-timey hamlet is the same stuff that would get bleeped here and now? The women make gabbling noises at one another. “Abortion,” the wall translates. “Pussy.” “Fuck.”

Parks is one of our greatest living playwrights. No other writer uses language as she does—it’s not just poetry in her hands, it’s paint. (We see it as much as we hear it, and don’t get me started on the beauty of the way she lays out her scripts.) So it’s wonderful that the Signature has turned itself into a kind of museum for her: in one theater-cum-gallery, her version of an El Greco crucifixion; in the other, her bitterly satirical equivalent of a Goya etching. Rothko thought his paintings spoke to each other when they hung on adjacent walls. When you hang these two plays together—they shout.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, the Village Voice, TheatreForum, and diversalarums.com.