Mark Sinker

Mark Sinker

Curious and gleeful, socially awkward and irritable: in the multidimensional characters of the beloved Moomin universe, a reflection of their creator’s dualities.

Tove Jansson, by Paul Gravett, Thames & Hudson, 111 pages, $29.95

• • •

Consider the weightier biographies of the Finnish artist Tove Jansson—Boel Westin’s from 2007, Tuula Karjalainen’s from 2013, Zaida Bergroth’s biopic from 2020. Aren’t they sometimes hinting that a superior fine artist was lost to her global success, as author and illustrator, with cartoons and books for children? Her beloved Moomins, small pale plump creatures with bean-shaped faces, an elusive, unmalicious type of troll with wild-animal ancestry but domestic human-ish concerns, are so familiar in so many languages that they barely need introduction (except for readers in the US, where they never quite took off). We do know the routine of delivery and the scale of maintenance of this imagined world sometimes left Jansson frustrated, drained, and bored. Expanding to include theater, TV and films, and franchise items, it became less and less the art she most wanted to make. Could she not have used the time and energy to paint more serious works: more landscapes, still lifes, and portraits to show in exhibitions?

Self-portrait with cast of characters, 1957. TM & © Moomin Characters.

A well-established scholar of comic-book art, Paul Gravett is matter-of-factly un-tempted by such a position in his tidily realized biography. With beautifully reproduced images on every spread, many in full color, this is a well-summarized chronology of Jansson’s projects and styles, with brief digressions into technique. It does touch on the gallery work and her later-in-life writing for adults, but Moomins make up most of its contents.

Born in 1914, Jansson was the daughter of a professional sculptor and a commercial illustrator. She began working for magazines as a teenager before finding her footing and local renown in the thirties and forties mocking big perilous beasts like Hitler or Stalin in the satirical magazine Garm. Out of this same leftish milieu emerged her first children’s books, and then the newspaper strips—as well as illustration work for other children’s classics, including Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

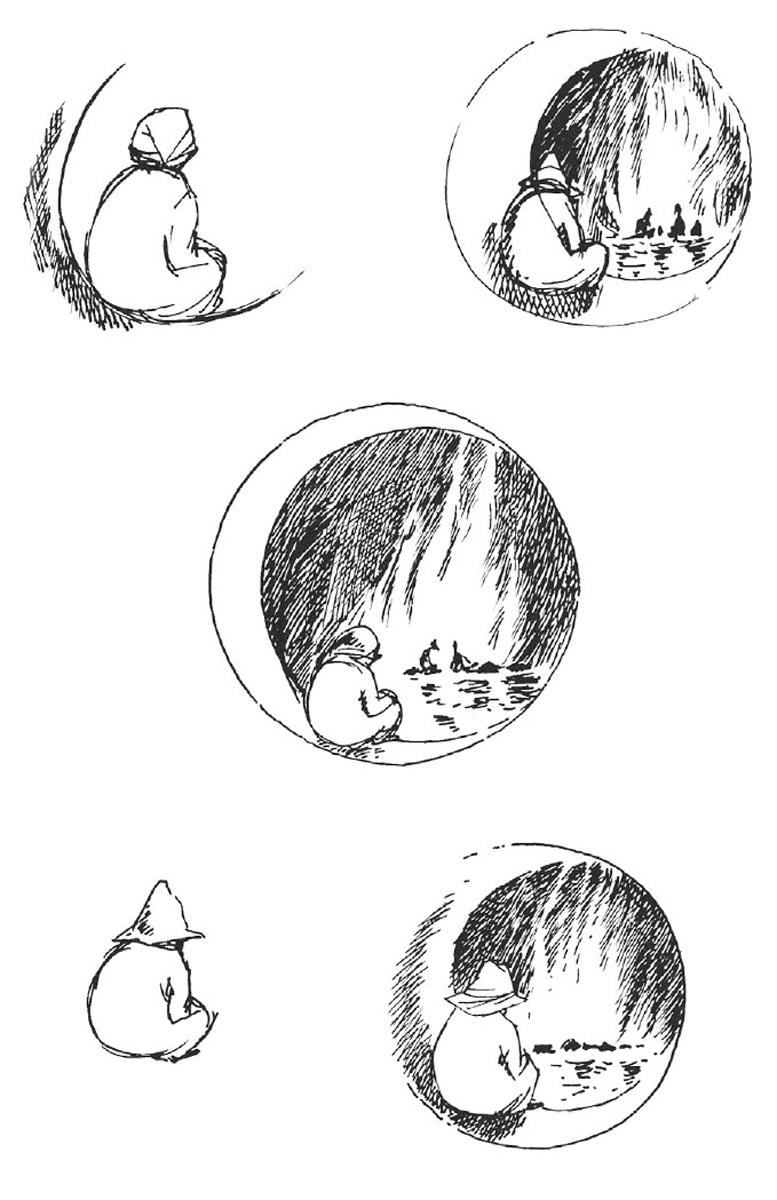

Trial versions of Bilbo Baggins sitting by the fire for The Hobbit, 1962. © Tove Jansson.

Socially and artistically, Jansson’s life seems everywhere in tension: she was a woman in a very male art scene; in lesbian relationships when this was illegal in Finland (until 1971, with lesbianism classified as mental illness until 1981); a minority Swedish speaker never entirely confident about the quality of her Finnish. But if all this at times demanded a certain double consciousness, the chief tension in her work was beneficial. She had always to think in two contrasting modes: the image and the written word. And in the unrealized gap between them there was inviting territory left for the questingly curious young reader to imagine for themselves.

For example, Gravett selects a black-and-white illustration from Finn Family Moomintroll (1948) to run as a full page. Here the hobgoblin’s hat is being rescued from a river, but with no hat visible in the picture, this would be impossible to decode without access to Jansson’s words: all we see is the character Snufkin’s unmistakable silhouette against bright moonlit water and Moomintroll up to his neck in same. Sharply backlit, this vignette stands out as a small square at picture’s center, surrounded by a deep border of darkly inked exotic jungle-like forest. Here and there small unidentified beasts watch from the margins, odd little folk with their own lives stopping to gawk. Shining eyes peer through the foliage, one pair—from within a tree root at bottom right—gazing straight out at us. We meet these little characters nowhere in the text, but only as our attention ranges the less-described reaches of the image.

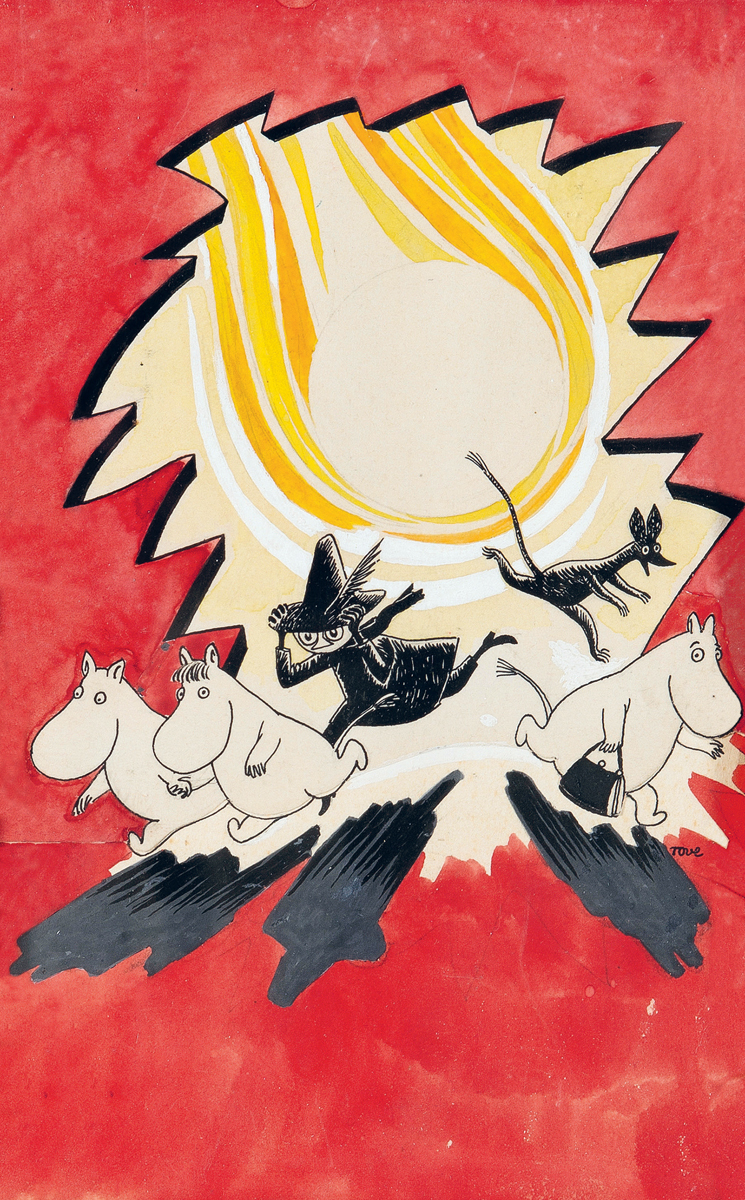

New cover for the rerelease in Finland of the Swedish-language edition of Kometjakten (Comet in Moominland), 1956. TM & © Moomin Characters.

Gravett in fact doesn’t discuss Jansson’s writing at any length, but to explore this duality of modes we surely must, because it includes so much material that’s tricky to deliver visually. Anxious but stubborn herself, she was a lucid observer of social awkwardness, her subject matter in her books being primarily worry: at disasters real and imagined (comet-fall, floods, unplanned chaos), but also at small-scale domestic panics (such as how to mollify unwanted guests). Affection (like Moominmamma’s patience) is a given in the text that’s amplified by the rounded shapes of many of the drawn characters, but far from these being angelic or merely spunky adventurers, their verbal exchanges are riven and driven by inner doubt and irritability, vainglory and simple fright, while the smallest regular character, Little My, has a spiteful glee that’s plainly very drawable, but a consistent comedy rhythm to her truth-telling that just isn’t.

The tiny marginal bystanders, the eyes and the beasts, had been a long-standing Jansson signature. Doodled proto-Moomins can often be spotted among the politicians in her wartime Garm covers, and in one of the two large 1947 frescoes painted in Helsinki Town Hall—a party scene that includes then-lover Vivica Bandler, whose father commissioned the murals, dancing in the center—Tove herself is in the foreground, gazing left out of the picture, cigarette in hand, wineglass and glass-sized Moomin on the table in front of her.

Meanwhile the strips (her first appeared in 1947, the last in 1959, after which her brother Lars took over both art and writing) are sometimes as busy as a Richard Scarry book with secondary characters, or better say types. Exploiting the size constraint (micro-narrative in just three or four squares), the strips everywhere hem the family in with this scurrying citizenry. Gravett includes several pages of proposed designs for these minor creatures, and Jansson is plainly enjoying herself as she melds vividly differentiated body shapes with proto–Pop art ink-line geometry. She wasn’t much taken with modernist abstraction—she found the bohemian left’s adherence to it a little bullying—but such flirtations here feel more like a holiday from the demands of the proper grown-up art that also nagged at her. If this mischief reflects her own torn nature, it also helps affirm the Moomintroll family as fretful if generous misfits, who tag along with the social routines and artistic conventions of bourgeoisie and avant-garde but establish their comfort zones where such norms break down, or perhaps begin to firm up again.

In Moominland Midwinter (1957), the breakdown, far from being unexpected, happens every year—except the family usually hibernates through it. But this year Moomintroll wakes, into a dramatically unfamiliar world, and now he’s the outsider as the winter-folk take this frozen landscape in their usual stride. In a striking image Tove loved enough to use more than once, Moomintroll watches from the shadows as bizarre figures, as yet unmet and closer to the traditional conception of the troll, caper in silhouette against the flames of their folk-pagan bonfire. The scribbled marginalia of earlier pieces move to the center of her interest and begin to be heard, to be written about. She would tire of Moomins: in Moominvalley in November (1970, the last volume), the art is autumnal, both foggier and scratchier, the family are absent from the entire novel, and others have invaded their house to await their return.

Gravett closes his book with a color painting from the 1961 Italian edition of Midwinter, in which a scared and bewildered Moomintroll is guided through a gorgeous frosted blue-and-black grove by someone in a sensible red-and-white striped jumper. This is Too-Ticky, modeled on the artist Tuulikki Pietilä, Jansson’s beloved life-companion, knowledgeable and practical—but both characters are absolutely also Jansson herself, as is the backdrop. Which are several distinct directions to be pulled in—big-eyed terror, candle-carrying unflappability, trees as stiff towering monsters with claws—but such tension in combination is the core of her art.

Mark Sinker has written about music, film, and the arts since the 1980s, at outlets including Sight and Sound, Crafts magazine, the Face, the Village Voice, and the London Review of Books. In the early 1990s he was editor of the Wire, and in 2019 published an anthology of essays and conversations about UK music-writing, A Hidden Landscape Once a Week: The Unruly Curiosity of the UK Music Press in the 1960s–80s, in the words of those who were there.