Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Revisiting the net artist’s Flash poem Separation / Séparation.

Annie Abrahams, Separation / Séparation, 2002 (screenshot). Image courtesy the artist.

Separation / Séparation, by Annie Abrahams, available here

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that museum and gallery exhibitions remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to reflect on an artwork that is particularly significant to them and that is easily viewed online.

• • •

Already in 1997, the internet was deemed “the public space of loneliness” by the prescient and pioneering net performance artist Annie Abrahams, who designed Being Human, a network of “online low tech mood mutators,” to intervene into that desolate affective sphere. Being Human is basically a website whose different iterations (archived by year, up to 2007, on bram.org) index a series of related but independent artworks, such as a page where audio recordings will reassure you in several different languages and a window where you can consent to an online kiss. I have gravitated to one of these “mood mutators” in particular when the outside world has seemed especially minacious: Separation / Séparation (2002), which I included in a 2013 exhibition in downtown Cairo that opened while the city was living under military-imposed curfew, and which I found myself searching for again more recently, during a very different sort of lockdown, in a bored moment of trying to find things on the internet that I used to love, many of which have now disappeared (part of the loneliness of the net). This bilingual interactive Flash poem is, fortunately, still online (at least for as long as we have Flash player, which is scheduled for oblivion by the end of this year).

Annie Abrahams, Separation / Séparation, 2002 (screenshot). Image courtesy the artist.

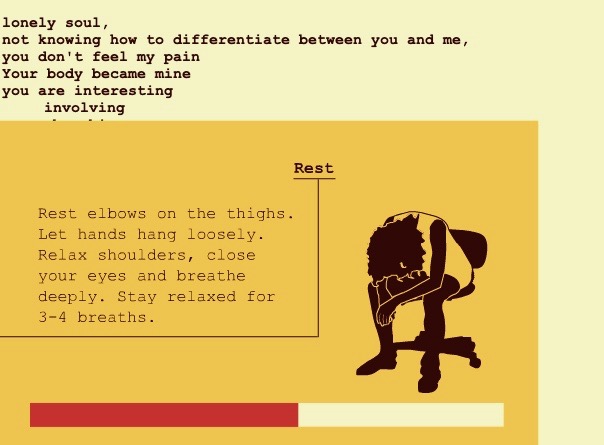

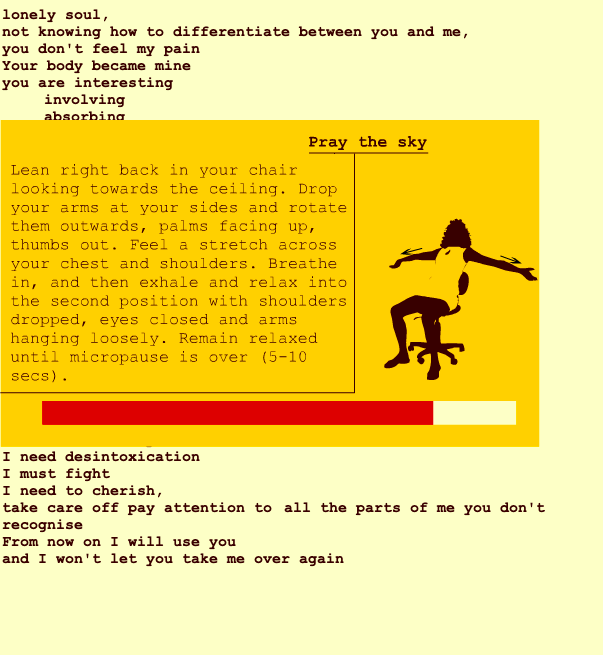

The first word of the poem is “lonely.” The text, available in English and French (the Dutch-born artist lives in Montpellier), was written by Abrahams during a stay in the hospital. It is paired with simple animated demonstrations of six different exercises for the treatment and prevention of Repetitive Strain Injury. You must click repeatedly on the pale-yellow field of a pop-up window to get the narrative to unspool, word by word, its story of pain, the lament of one suffering body being taken over by another, demanding, unfeeling one. The suffering seems to be caused by the melding of human and computer, but it’s not totally clear who is suffering. It’s most likely that the human user is despairing at the computer’s homesteading of her person, but it might be the other way around—perhaps she’s anguished at her own displacement of herself into the computer. Or is it the computer that is in need of succor, constantly being manipulated and exploited by this insatiable human? “How to relax a computer?” the poem ends. “How to massage a computer?”

Annie Abrahams, Separation / Séparation, 2002 (screenshot). Image courtesy the artist.

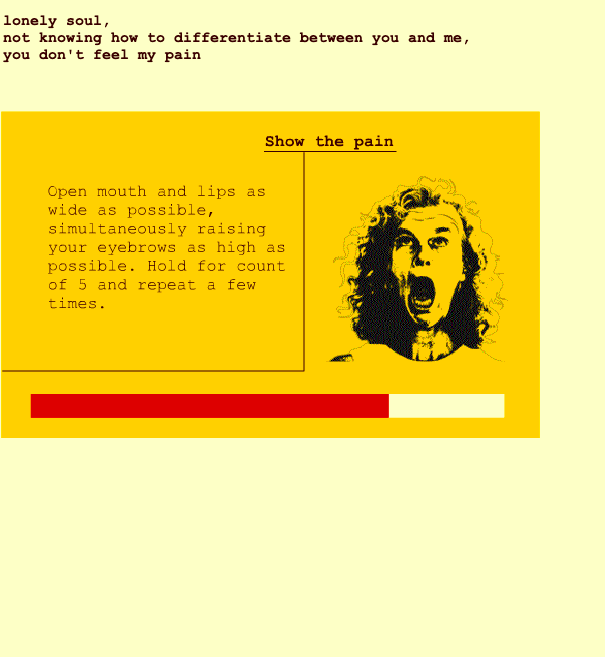

In an apparent effort to soothe the ambiguous affliction described above, there are sudden breaks in the poem during which the user is invited to perform a given physical exercise that is thematically related to the text. For instance, the first time the word “pain” appears, at the end of the third line, a little rectangle pops up within the pop-up titled “Show the pain,” illustrated with a sketch of the artist’s face teaching how to work out our facial muscles by widely grimacing. Get to the word “caress,” and you’re instructed how to “caress your back”; the word “fight” prompts us to adopt a pose called “take courage.” A red bar inches to the left of the screen to indicate how long we’re to hold the pose: an exercise might pause us anywhere from twenty seconds to a full minute, which can feel agonizingly slow in internet-time. (A recent study suggested it takes just under sixty seconds of waiting for content to buffer before the average user is overcome by “load rage.”)

Annie Abrahams, Separation / Séparation, 2002 (screenshot). Image courtesy the artist.

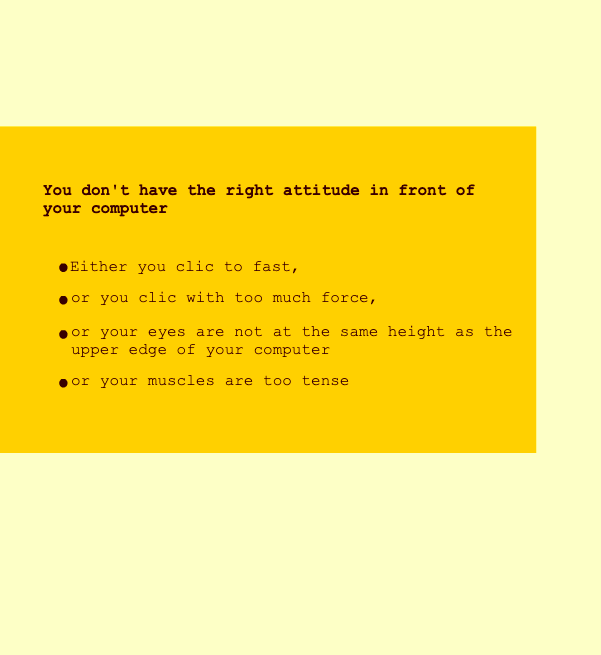

Even though I know the artwork well, I still unconsciously start to click faster and faster to speed things up, nettled by the slowness of the exercises, or how sometimes it will take two or three clicks to get to the next line of the poem. But beware: such behavior can trigger the artwork to spit you into a timeout screen. “You don’t have the right attitude in front of your computer,” it admonishes, listing your potential offenses as you wait, for at least ten seconds, to return to the work. A 1993 manual on “usability engineering” held that a user will pay attention to a webpage dialogue for a maximum of ten seconds before they move on to something else; by 2015, Microsoft claimed our attention spans had shrunk to eight-second intervals, shorter than that of a goldfish. With these timeouts, Abrahams is forcing us into idleness for almost longer than our content-craving brains can bear.

Last year, a Republican senator notorious (and often ridiculed) for his expansive plans to regulate the internet introduced a bill that would bar social media companies from using “human psychology or brain psychology to substantially impede freedom of choice,” such as by compelling users to stay for longer on a site or app by trapping them in addictive behavior, like interminable downscrolling. That kind of reminds me of what Abrahams does in her pieces, but to stranger, more experimental ends—ones that might expand our field of choice. She has described herself as a researcher testing novel ways technology could impact our emotions, communications, and actions. Across her body of work, she tries to implement protocols that could provoke messy, unpredictable human behaviors (“Human behavior is my aesthetic material,” she wrote in 2011), what she calls a person’s “hidden code,” to break participants out of programmed conduct that’s so hard to deviate from. Here, too, in Separation / Séparation, Abrahams anticipates our impatient behaviors and both goads us into them, so we become conscious of these automatic operations, and induces us to comport ourselves differently, to adopt a gentler attitude in front of the poor pounded-on computer.

Annie Abrahams, Separation / Séparation, 2002 (screenshot). Image courtesy the artist.

This is also to say that Separation / Séparation shakes me back into myself, makes me itchily aware of my being, instead of allowing me to believe I have dissolved into an immaterial receptacle for receiving entertainment, which is how I most enjoy feeling in front of a screen. How annoying it is to be reminded that my self is sitting here before the screen, of the ill temper that instantly appears if I’m not immediately gratified when I am engaged with my mechanical companion. How vexing that I’m now unhappily aware that my back is in knots as I sit hunched over this keyboard.

I think I’ve been drawn to think about Separation / Séparation in moments of duress because of Abrahams’s focus on these peevish reactions. Scholar Sianne Ngai has famously written on such minor, ignoble emotions, like irritation and anxiety, which are usually considered too awkward and inconsequential to constitute a subject for Art. She suggests these “ugly feelings” can paralyze us. While rage can propel us into the streets, something like nervousness, allegedly more trivial, just holds us by the backs of our necks, so that we waggle our little limbs and expend lots of energy without moving anywhere. This is also the muddled, disorienting experience of precarity, as described by Lauren Berlant in Cruel Optimism. Indeed, during the most precarious moments I’ve had to wait out, whether hiding from the violence of a military coup or the peril of an invisible virus, I can’t recall feeling blinding fury or transcendent fear. It’s something more like a hard-to-pinpoint, saturnine discomfort. It’s bearable, but it prickles up and down my spine and makes it difficult to think, it inspires me to throw small ineffectual tantrums and seek escape from consciousness. That escape comes easiest through technology, but not here: Abrahams bars the door to fugitive, algorithmic reprieve.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.