Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

The chaos of memory: a foraging artist receives her first solo show outside of Poland.

Erna Rosenstein, Poświata (Afterglow), 1968. Oil on canvas, 22 7/8 × 26 inches. Photo: Marek Gardulski. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon a Time, curated by Alison M. Gingeras, Hauser & Wirth, 32 East Sixty-Ninth Street, New York City, through December 23, 2021

• • •

Born in 1913 in the sometimes-Polish city of Lwów to a well-off Jewish family, Erna Rosenstein demurred convention from an early age. In high school, rebuking her family’s wealth, she joined a band of pseudonymous teen-girl Communist rebels. Rosenstein’s father, terrified, sent her abroad to clear her head. In the West, she saw the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich and the first Surrealist exposition in Paris, after which she would gleefully hoist Breton’s “invisible ray” onto her shoulder, the precepts of this secret society illuminating her way for the rest of her life. Her family finally allowed her to return to Poland to study at Kraków’s prestigious fine arts academy, where she defied them yet again, infiltrating the avant-garde Krakow Group helmed by that perverse imp of underground theater, Tadeusz Kantor.

Then the Nazis came. She saw her parents brutally murdered by a Polish smuggler who had promised to save them. She survived, and averred amnesia for the next three years, but never stopped writing poetry or making art. After the war ended, she was active in the Communist party under the new Soviet regime, but she risked her freedom, if not her life, by publicly refusing its Social Realist mandate, stubbornly pursuing a Surrealist aesthetic that was ideologically forbidden under Stalin. It wouldn’t be until after ’53 that her star would start to officially rise. In the 1960s and ’70s, she showed at Poland’s most important galleries, her work was collected by the national museums, she was championed by the most prominent critics. She was one half of an art-world power couple, married to Artur Sandauer, a heavy-hitter literary critic, friend to Bruno Schulz and Witold Gombrowicz. This association initially helped her career, offsetting the professional setbacks that came with being a woman. Until it would hurt her, due to Sandauer’s late-in-life public support of the osteoporotic Communist regime instead of the Solidarność protests in the late ’80s, a bet so bad she was tainted by association. After the revolution, her paintings were quietly removed from museum walls; she died in 2004.

Over the past decade, though, curators Dorota Jarecka and Barbara Piwowarska have been assiduously restoring Rosenstein’s legacy, organizing a massive three-part retrospective of her work in different cities across Poland and issuing a significant volume of scholarship, I Can Only Repeat Unconsciously. Their efforts caught the attention of American curator Alison M. Gingeras, who has now organized at Hauser & Wirth the first solo exhibition of Rosenstein’s work outside of Poland and the publication of the first English-language monograph on the artist, which includes a vital contribution from Jarecka.

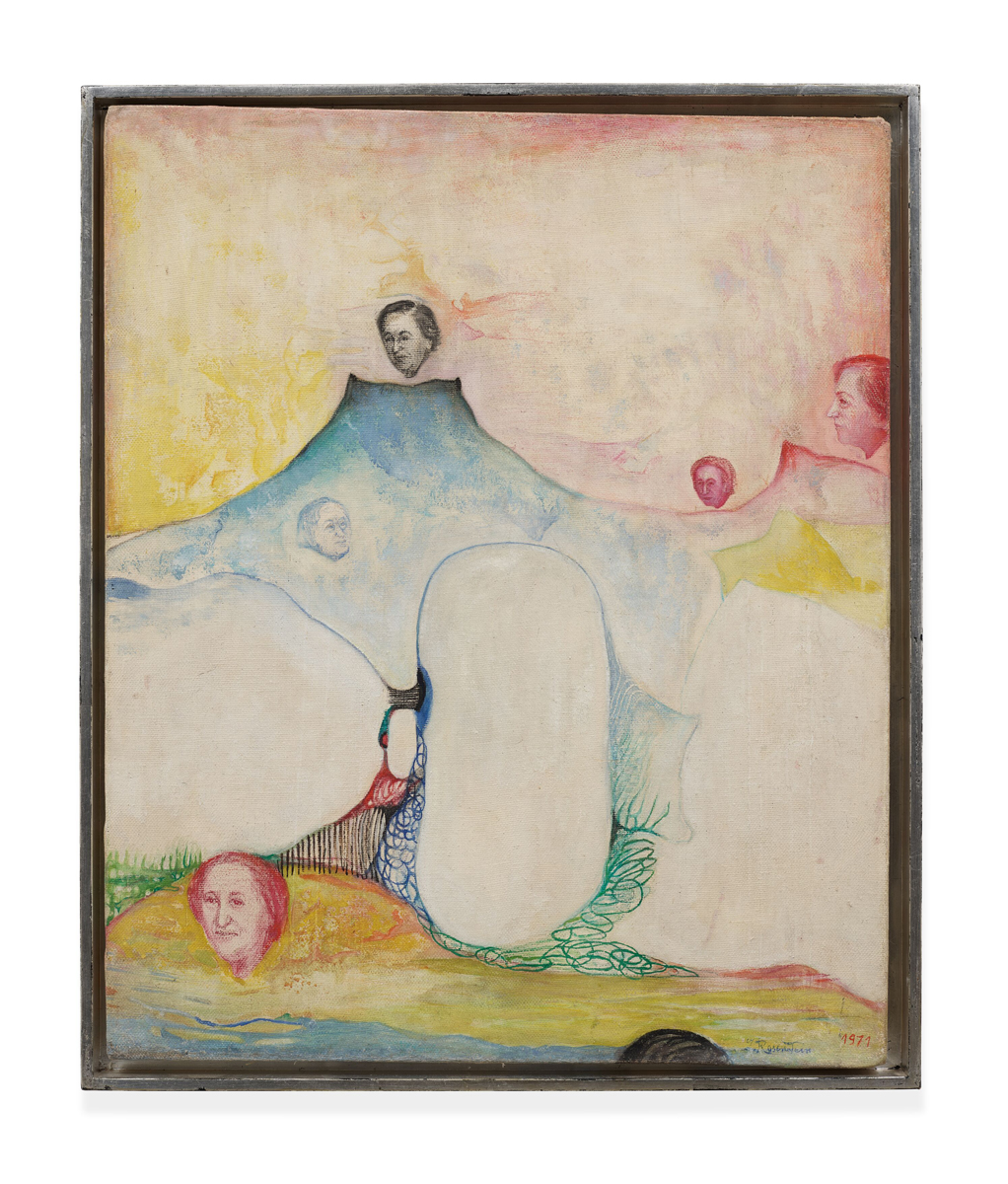

Erna Rosenstein, Osobna pora (Separate Season), 1971. Oil and mixed media on canvas, 29 × 23 7/8 × 1 inches. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

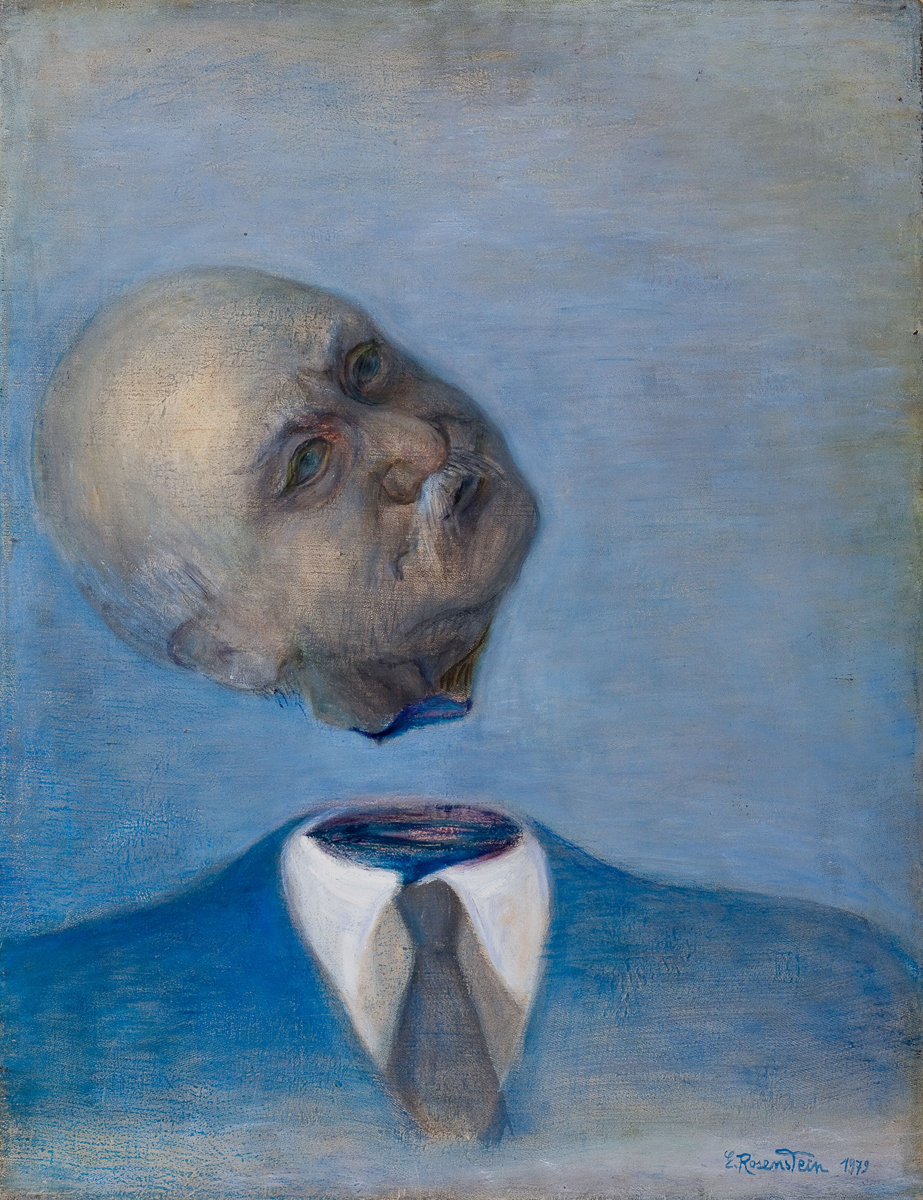

Once Upon a Time is straightforward in execution, the forty pieces on view organized chronologically and with Rosenstein’s biography as the guiding framework. It reveals, among many things, the dramatic push-me-pull-you tensions in Rosenstein’s practice: between a loose and scrawly biomorphic abstraction and a weird, hard-edged, Leonora Carrington–esque figuration; between a tender celebration of the natural world and a visceral horror of the human; a frantic overload of detail, a material overstuffing, and a devastating emptiness, an impossibility of representation. We see one set of tensions, for instance, in the twinly serene and nightmarish oil-on-canvas portraits Dawn (Portrait of the Artist’s Father) and Midnight (Portrait of the Artist’s Mother), both 1979. The paintings show the composed and vaguely beatific faces of her dead parents as their severed heads placidly float against fields of crepuscular blue (the father) and inky black (the mother), a thin, disturbingly lucid line of shocking red limning the edge of the maternal neck. Their acephalous torsos are squared proudly forward, as if there were nothing out of the ordinary.

Erna Rosenstein, Świt (Portret ojca) (Dawn [Portrait of the artist's father]), 1979. Oil on canvas, 25.8 × 20 inches. Photo: Paweł Czernicki. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

Rosenstein had been creating such troubling images since shortly after the war, when she miraculously recovered, in Kraków, some negatives of her childhood photos, which the photographer had kept buried underground until the fighting ended. The negatives became the source of many of the representations of Rosenstein’s parents, whose fixed expressions she drew over and over, a third-hand transcription of a second-hand trace, now the only physical thing remaining to her of a mother, a father, a family, a generation, a world, all lost.

Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon a Time, installation view. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

One of these portraits was included in Rosenstein’s first retrospective, in Warsaw, in 1967, organized and designed by Kantor himself. The Hauser & Wirth presentation invokes that show: in a downstairs gallery, a suite of surreal abstractions appears with each painting hung on the projecting waves of a crenulated wall—a bookish nod to a similar wall Kantor had invented for that earlier exhibit, which was far more insane (as if in an abattoir, paintings were hung in metal cages and in cramped dark stalls). The portrait was mounted inside of a large cabinet, also on view here. Conceived as an artwork in its own right, Szafa (c. 1960–2004) had been Rosenstein’s personal armoire, and was emptied out to serve as a vehicle for her paintings, the doors decorated with a hyperactive collage of papers (exhibition invites, postcard reproductions of artworks, photocopies of Rosenstein’s own drawings).

Erna Rosenstein, Szafa (Closet), c. 1960–2004. Wardrobe cabinet with collage and assemblage elements, 70 1/2 × 19 5/8 × 42 1/8 inches. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

Szafa is the conceptual link to the collection of junky found-object assemblages piled on plinths in an upstairs gallery (the likes of which would eventually consume Rosenstein’s entire Warsaw studio-apartment, where chocolate boxes were stapled to the wall and pictures pasted everywhere, strings of trash crisscrossing the space and her own art and the art of her friends hung thickly among it all). Rosenstein’s veneration of discarded things and determination to resuscitate them through unexpected juxtapositions is partly indebted to her early research in Surrealism. But scholar Bożena Shallcross also argues that Rosenstein’s foraging garbage to reanimate was a radical form of resistance against human ruination, one “expressed by the ethical non-destruction of things [and] the rejection of their disposability.”

Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon a Time, installation view. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

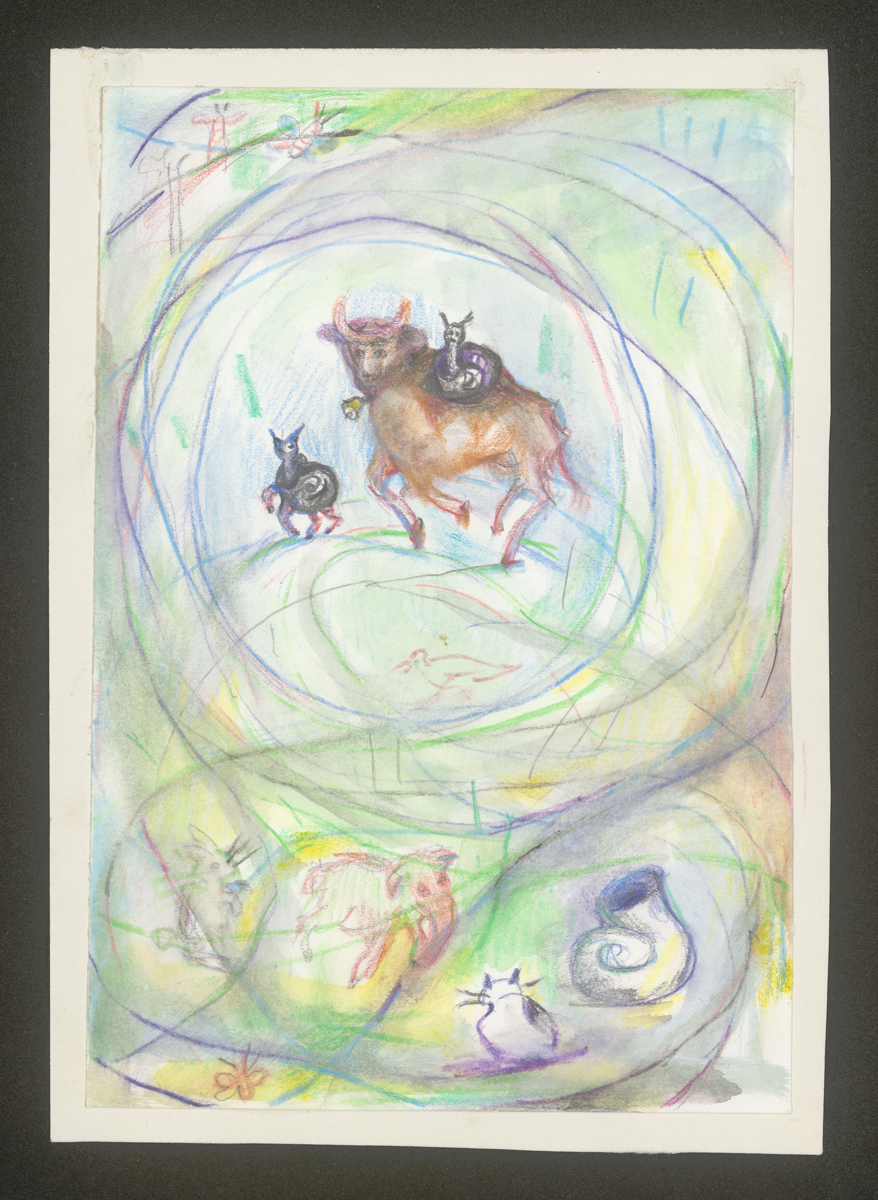

Andrzej Juchniewicz has similarly suggested Rosenstein’s worldview was presciently posthumanist, informed by a desire for an egalitarian, interspecies, and interobject community of care. In her poetry, human and plant become one—dying bodies stay “in the leaves / In blur / In the shimmer of trees / The grass repeats their steps”; the earth beats blood into human veins that beats to the same rhythm as the grass. In Once Upon a Time, Rosenstein’s compassionate invitation to a new homeland of interbeing reaches a crescendo in her fairy tale “Tiny Tale of Snail and All His Friends,” plates from which are hung on the walls around the assemblages, about the trials and triumphs of a snail and a cow who fall in love and have a snail-cow babe. The illustrations are fittingly gentle and sweet: watery pools of primary colors, animals expressed in sensitive, delicate, curly-minded lines.

Erna Rosenstein, Historyjka o przygodach ślimaka i jego przyjaciół (Tiny Tale of Snail and All His Friends), 1997–2001. Crayon and watercolor on paper, 8 1/4 x 5 3/4 inches. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

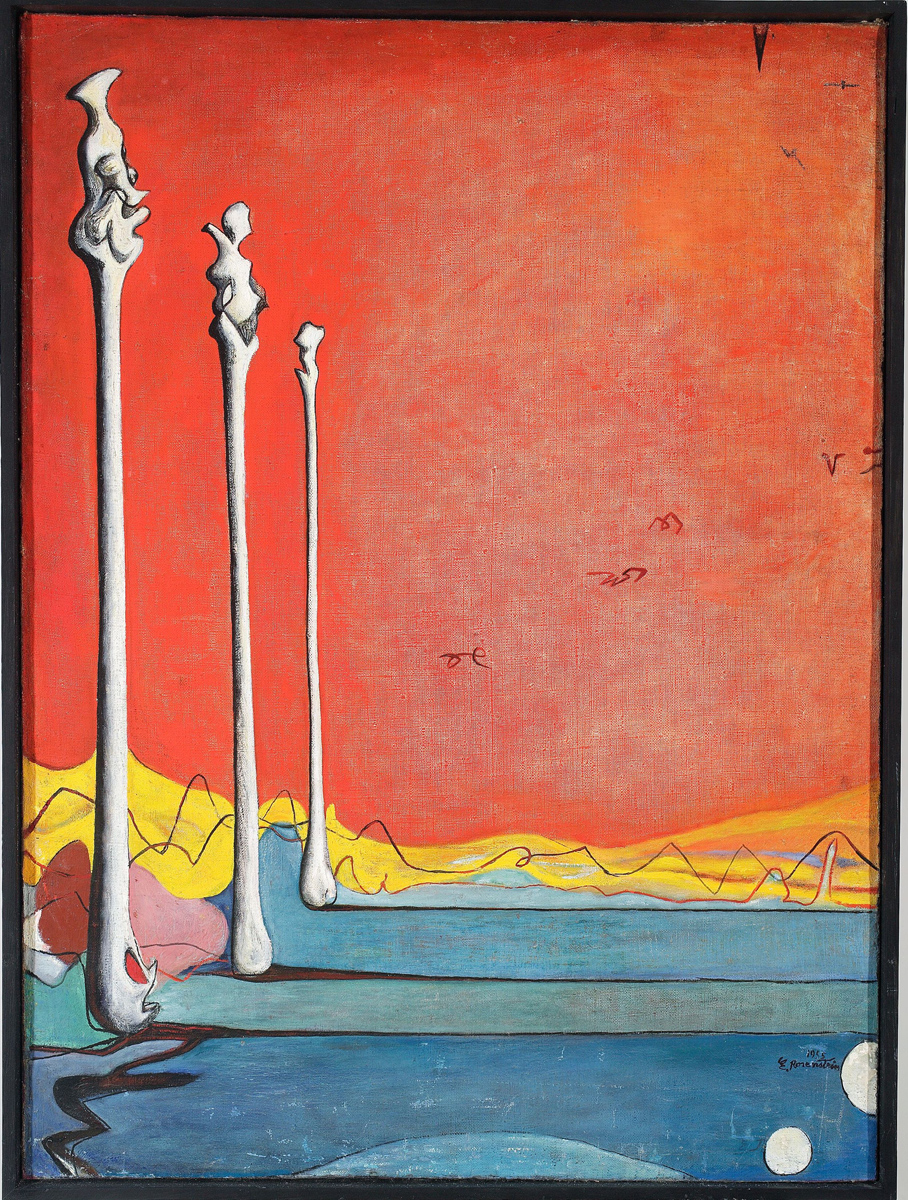

Throughout the works, and in the selection of poems translated in the catalog, we also see Rosenstein’s other abiding preoccupation: memory. She writes the Holocaust as a rupture with reality she can’t quite recall—she writes about how words can become blank, like her mind, like her eyes, how memories run backward. She paints a memorial of jutting, criminally white bones rising energetically against a lurid carmine sky. She writes a “book of eternal remembrance,” and adorns it with delicate, perishable filaments, like strands of hair.

Erna Rosenstein, Pomniki (Monuments), 1955. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 23 5/8 inches. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Foksal Gallery Foundation. © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer.

If Rosenstein struggled to reproduce the chaos of memory, she herself, and her practice, has been subjected to a cultural amnesia, especially after the 2015 re-entrenchment of the nationalist Law and Justice Party. Their ethno-fascist memory laws are working to dissolve a person like her, to make illegal the kind of memories she had. This is the urgency behind the work of Jarecka and Piwowarska, and behind Once Upon a Time—because curating, art history, and art criticism are all forms of remembering that can agitate against the necro-politics of forgetting. “I am invisible by habit,” Rosenstein wrote. “Notice me.”

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.