Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

At a SculptureCenter show, enigmatic erasures and self-conscious looking.

Searching the Sky for Rain, installation view. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Searching the Sky for Rain, SculptureCenter, 44-19 Purves Street,

Long Island City, New York, through December 16, 2019

• • •

The “minority” must define itself with a clear and voluble voice in order to tip the imbalance of power away from the “mainstream,” artist Charles Gaines points out in his catalog essay for The Theater of Refusal—Black Art and Mainstream Criticism, an exhibition he curated in 1993. But this political fact creates a conundrum. The mainstream will always confirm itself, and its belief in its own stable, universal identity, through opposition to the minority’s self-articulation. In fact, the mainstream demands that the minoritarian render herself easily legible, so that the mainstream can understand itself as not that. Gaines applies the image of a double-edged sword: the minority must assert its identity, but its subjectivity will always be flattened and subsumed by the majority to reaffirm the latter’s primacy through comforting stereotypes.

Gaines, in the company of many other artists, has long been thinking through this paradox, and about capitalism’s related and voracious cooption of fixed identity categories, all of which are part of a social process that Karen and Barbara Fields have usefully termed racecraft. At SculptureCenter, Sohrab Mohebbi has curated an impressively thoughtful exhibition, Searching the Sky for Rain, which, as he told me during the press preview, is anchored in writing by Gaines (who also has two pieces in the show), the Fields, and others seeking a way to elude this double-edged obligation to perform identity.

Mohebbi’s curatorial statement claims the exhibition and the artists in it “disregard the ways in which the art industry regulates, classifies, compartmentalizes, and essentializes difference into sanctioned categories.” Those categories, though easily inferred, are not named, nor is any alternative offered to get away from this process of racecraft (or gendercraft, etc.), nor does Mohebbi articulate any guiding principle tying the assembled artworks together other than the shared refusal of their makers. He clearly states what the exhibition is not doing, but lets the audience interpret for themselves what its enigmatic doing might be, without citing his thorough research to provide interpretative clues. His honeycombed statement reads like a series of organized absences.

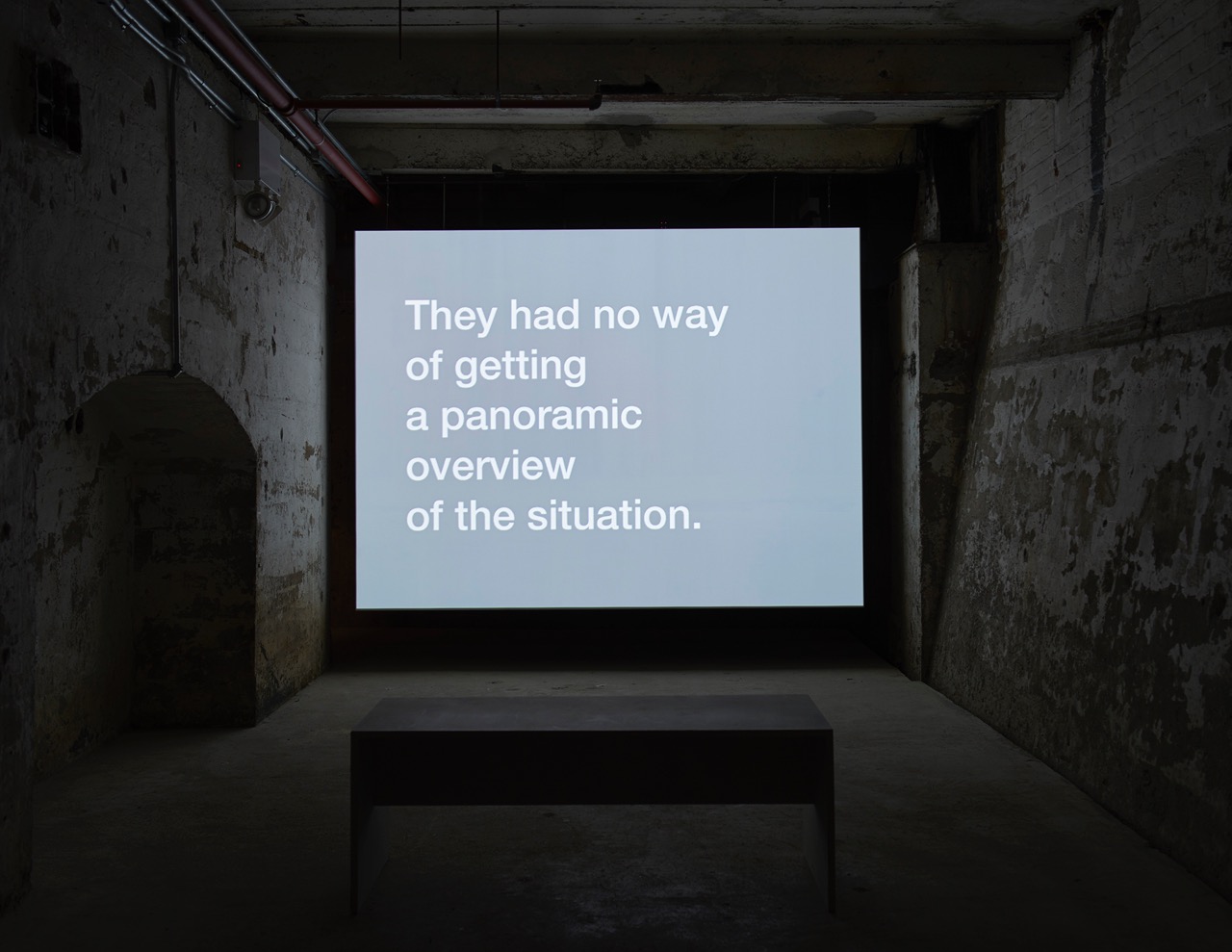

Tony Cokes, Evil.27.Selma, 2011 (installation view). Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, Hannah Hoffman, and Electronic Arts Intermix. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

A number of the forty-five artworks on view are also structured by what they leave out. Tony Cokes’s nine-minute video Evil.27.Selma (2011), projected onto a screen in SculptureCenter’s dark and cavernous basement, subtracts the traditional vocabulary of the visual arts—things like imagery or color or any form of optical seduction—leaving only frame after frame of white text on an institutional-gray background. The video invokes the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, which Cokes’s collaged text says was so effective because, as it took place pre-television, it was “without a pre-existing visual template.” The boycott activists had to depend on their faculty of imagination, which allowed them to develop “fantasy ‘what if’ situations,” and ultimately create “the invisible rudiments for a vernacular of possibility.” Image, especially image-as-evidence, can “actually slow down transformation”—and so Cokes voids the image out of the video.

Jacqueline Kiyomi Gordon, Noise Blanket, Nos. 11–16, or Everybody’s Got Choices, 2019 (detail). Silicone, aluminum, vinyl, yarn, polyester filling, speakers, noise file filtered to the frequencies subtracted by the acoustics of the sculpture. 120 × 120 × 130 inches. Courtesy the artist and Empty Gallery. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

If Cokes invalidates the image in his work, Jacqueline Kiyomi Gordon erases the noise out of Noise Blanket, Nos. 11–16, or Everybody’s Got Choices (2019), one of the first works encountered in the upstairs gallery. Inside a mildly sagging white tent reinforced with two interior curtains of clear plastic panels, speakers play a ghostly soundtrack. The artist had made field recordings in and around the SculptureCenter (capturing zooming traffic, an old building’s clicks and clangs), then had a sound engineer process that ambient din out of the audio file. The result is a subtle drone; as sound from other artworks bleeds into the tent, the listener must concentrate terribly hard in order to mentally trace this sound’s contours, to imagine something like negative aural space.

Rafael Domenech, Tactics for a new architecture (excerpts from Severo), 2019 (detail). Styrene, 3M adhesive, fluorescent light bulbs, vinyl, building, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

It takes careful and attentive listening to hear nothing; likewise, the exhibition as a whole requires careful and attentive looking, which sometimes involves a hunt for the artwork indicated on the exhibition map—another form of erasure, perhaps: the obviation of how we’re used to looking at an exhibition. Back downstairs, I stupidly wandered up and down one of the labyrinthine basement’s corridors, hunting for Rafael Domenech’s Tactics for a new architecture (excerpts from Severo) (2019), until I finally noticed one wall was discretely covered with a white Styrene skin. I didn’t think to gaze upward, but instead had to be told that the artwork continued on the ceiling, where vinyl letters are stuck onto long tubes of harsh fluorescent lights to create a poetic and oblique narrative in Spanish and English (these lightbulb-poems are also found at the top of the stairwell going back to the first floor). Also on the first floor, a glazed pottery by ektor garcia (tocado, 2019) hides atop a doorway; and way up high, close to the soaring ceiling, a sensuous piece of dirt-smudged rawhide dangles from the clerestory windows: Rindon Johnson’s The stage is no place for the riot (ongoing). You have to look around and crane your neck and squint to see some of these artworks—there is no pretense of a neutral, standardized act of viewing. You are acutely aware of yourself as you try to see.

Rindon Johnson, The stage is no place for the riot, Ongoing (installation view). Rawhide, dirt, water, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

While other threads could also be plucked out of the show (Domenech’s interest in reordering architecture continues in two pieces by Becket MWN; Riet Wijnen and Johanna Unzueta share a formal interest in beautiful abstract geometries; there’s a voluptuous excess in the works by Johnson, Carmen Argote, and Mandy El-Sayegh), I still often felt bewildered in the midst of all of this, in part because Mohebbi consciously chose to keep didactics to a minimum. There are no artist biographies in the exhibition handout, nor are the artists identified by nationality or gender or any other identity category, so I couldn’t project any stereotypical assumptions as to their intentions. But part of my bewilderment was also probably due to this acute awareness of myself in the act of viewing; as a person whose identity markers firmly place me in the mainstream, I have rarely been asked to account for myself, and the myriad forces that shape my subjectivity; this fact left me on uncertain ground as I encountered these artworks created by other subjectivities that were not been pre-packaged for my understanding. Bewilderment can be uncomfortable, which is a part of why the mainstream is so often angered when it finds things inscrutable. But discomfort is not the same thing as harm; it is an inevitable sensation during a process of change, or when trying to decenter one’s own ego.

Searching the Sky for Rain, installation view. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Searching the Sky for Rain may operate by removal, but it is not empty—it is filled with so many, often beautiful, somethings. It’s just that I find I cannot name all of them, nor the ties binding them together; or maybe they need to be conjugated with a subtler grammar than the one I know—something like Cokes’s vernacular of possibility. His subjunctive “what if” constructions reminded me of how some languages are graced with special, specific irrealis moods, like the oblique, which can be used to express an experience that was not lived by the speaker, but was learned from others; or mirativity, which allows one to stress astonishment at the unknown or recently learned. Perhaps sitting in uncomfortable bewilderment a while could lead me to think of more nuanced declensions to articulate those astonishing things I do not yet know. Or perhaps it is not for me to find this language at all, but instead to learn the grammar of others as they give language to something that is not mine.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns.