Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Dioramas and faked archival documents: the Lebanese conceptualist interrogates the slippery realities of art and war.

Walid Raad: We have never been so populated, installation view. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad. Pictured, left: Walid Raad, Letters to the Reader_I, 2014. MDF wood and paint, 94 1/2 × 48 × 26 inches. Pictured, right: Walid Raad, Letters to the Reader_II, 2014. MDF wood and paint, 94 1/2 × 48 × 26 inches.

Walid Raad: We have never been so populated, Paula Cooper Gallery,

524 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through April 16, 2022

• • •

Walid Raad is worried something’s happening to the artworks. At the start of his current exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, We have never been so populated, he explains in a discreet wall text that “while visiting the recently opened Museum of Modern Arab Art in Beirut, I noticed with great surprise that most paintings on display had no shadows.” Were they taken by religious zealots? Did they simply grow bored of lingering behind the frames? He decides to carve hollowed-out forms to act like magnets that might lure the shadows back. This is his 2014 series Letters to the Reader, nearly eight-foot-tall MDF boards painted in trompe l’oeil style to resemble walls in museums, complete with baseboards and perspectival parquet floors, one bold shape lasered out of each. And though he lies in the last line of the text that “thus far, not a single catch,” we can see the truth for ourselves: the three examples on view project off the “real” walls so that, beneath the neurotic artificial glare of the gallery lights, many shades of darkness (faint and sharp and thick) fall from the paintings’ edges and into the gashes in their surfaces.

Raad works in series, and may create many variant series based on the same theme, and organizes all those sub-series into one big series-project. (Unnecessary organizational complication is a basic unit in the fractal of his practice.) Letters to the Reader belongs to Scratching on things I could disavow (2007–), an ongoing “investigation” into the mega-wealthy mega-museums of Western style (the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the ever-delayed Guggenheim Abu Dhabi) and other spectacular art world displays (biennials, fairs, contemporary art spaces funded by Ford or analogous foundations) that have been emerging in North Africa, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula since 9/11.

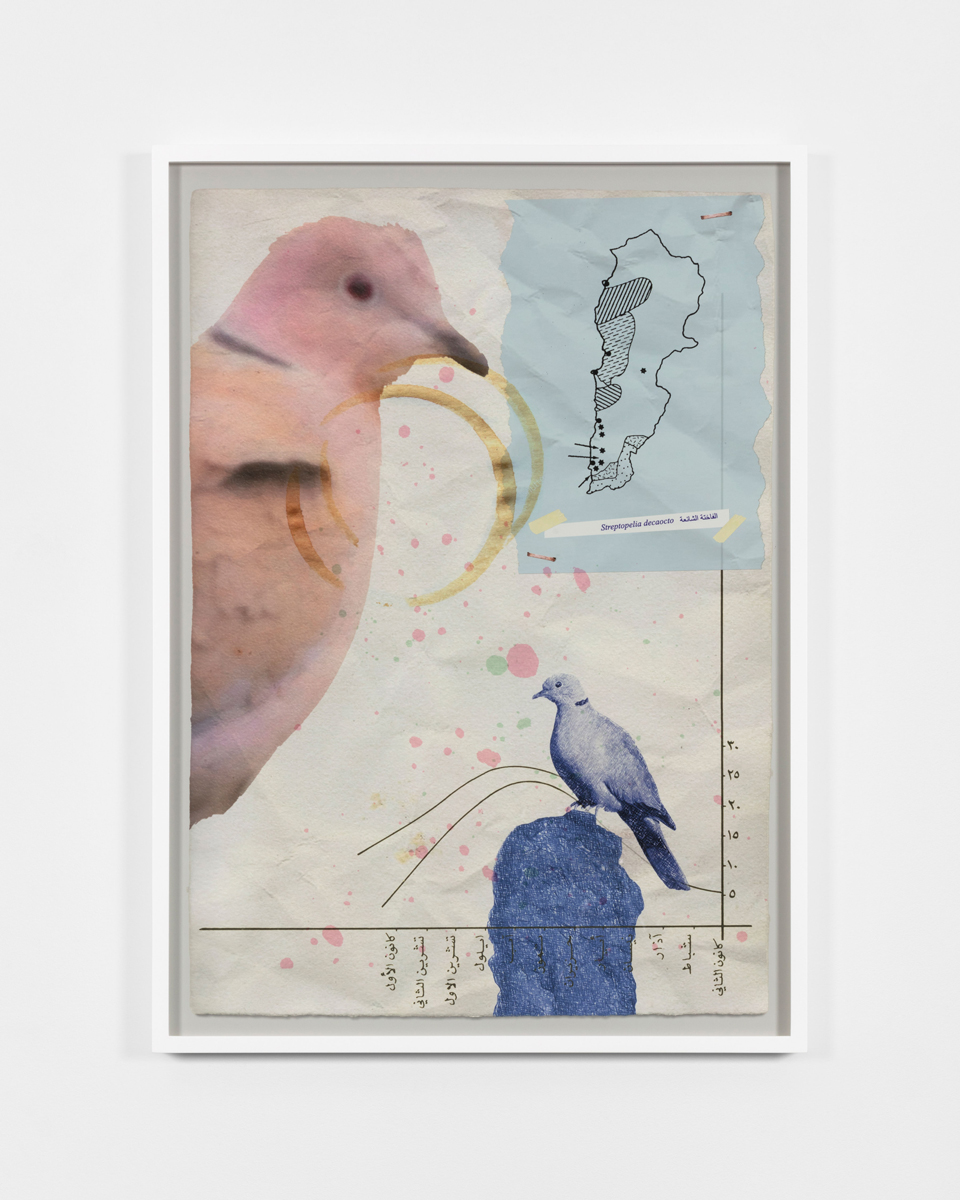

Walid Raad, We have never been so populated_Plate I, 1997/2020. Archival inkjet print, 32 3/8 × 23 1/8 inches. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad.

Raad came to critical renown and market success with The Atlas Group (1989–2004), a supposedly forensic unearthing of “true” histories of the Lebanese Civil Wars (1975–91) in which Raad grew up. (He was born in Chbanieh in 1967, moving to the US as a teen in 1983.) The Atlas Group works mingle “real” source materials in imagined discursive environments voiced by unreliable narrators, presented via Raad’s signature PowerPoint presentations and in exhibitions where oblique images are hung in rows or grids and accompanied by speculative wall texts. The two examples at Paula Cooper, installed in rooms to the left of the entrance, take gentle symbols of peace (the bird, the flower) and nonchalantly enlist them in deadly campaigns. First are the seven archival inkjet prints that comprise 1997’s We have never been so populated (reprinted in 2020), which collage watery images of birds with fragments of maps, diagrams, and other signs of the administration of war. We’re meant to believe these are notes from a right-wing Christian militia that had launched a failed campaign to send invasive bird species into enemy territory to destroy their local ecosystems.

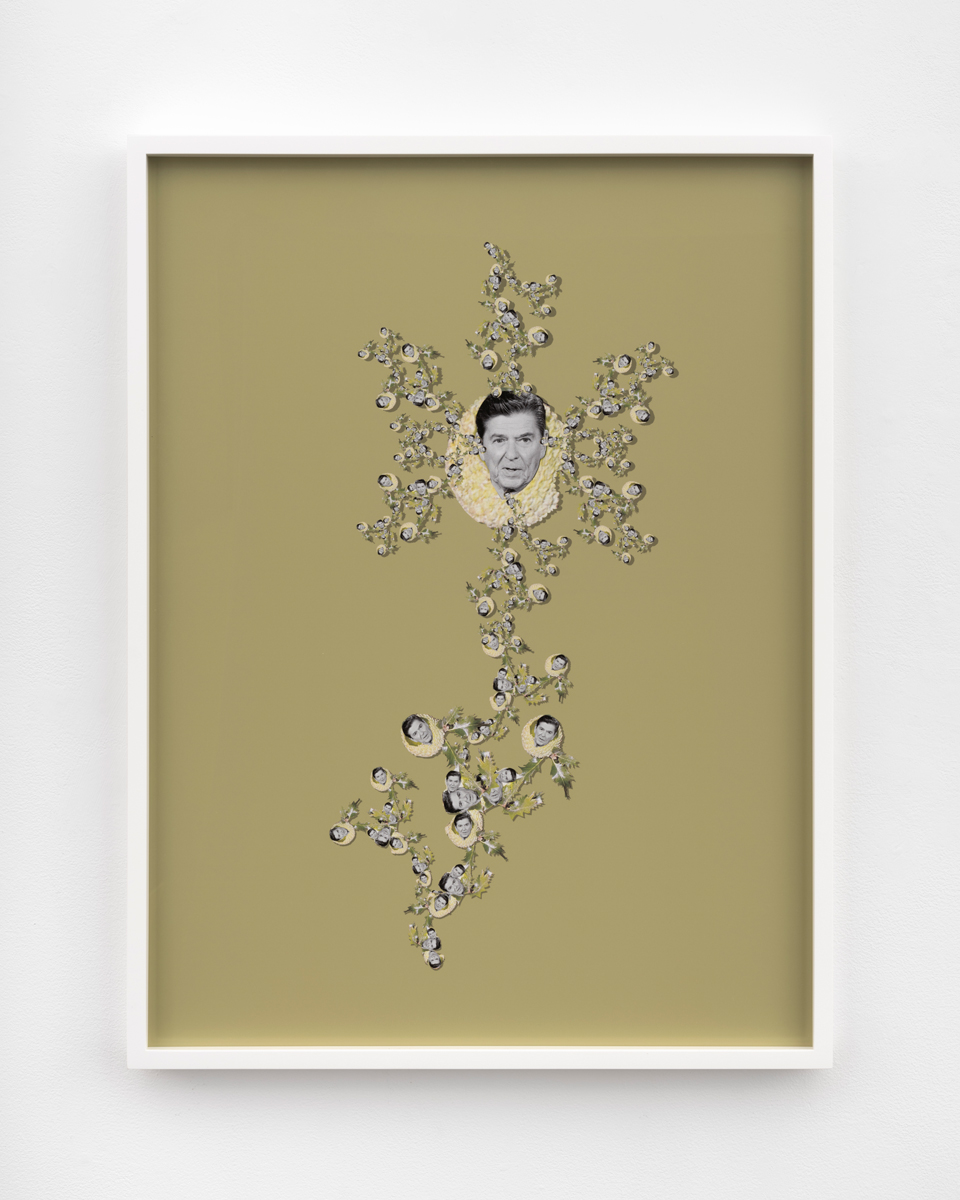

Walid Raad, Better be watching the clouds (again)_Reagan, attributed 1993/printed 2021. Pigmented inkjet print, 30 × 22 1/2 inches. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad.

Ten inkjet prints from Better be watching the clouds (again) (attributed 1993, but printed last year) are hung in the adjacent room. A different bouquet of flowers, whose petals are pasted with the faces of various political and military leaders repeating in swirling patterns, appears on each bright monochromatic image. These, Raad says, “were made by Fadwa Hassoun, an intelligence officer in the Lebanese Army,” in the 1970s and 1980s, to remember the floral code name she had assigned to each of the men.

Walid Raad, Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you_I, 2022. Single channel video, looped, no sound; 6 paper cutouts. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad.

The exhibition’s money shot is a brand-new installation that returns again to nature and the war, Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you (2022), situated at the back of the gallery’s central space. Three looped black-and-white video projections of towering waterfalls silently gush from the tops of the walls in a gorgeous plummet to the floor, where Raad has lined up a row of small paper dolls in front of each cascade. The videos are purportedly of “three particularly beautiful Lebanese waterfalls” that local militias, during the conflicts, named “after the leaders of the countries backing them.” (The dolls are photographic representations of some of those smirking heads of state.) “And when the alliances shifted, they simply decided to rename the waterfall again, and again, and again. Locals today refer to all waterfalls as the Fickle Falls.”

Walid Raad, Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you_III, 2022 (detail). Single channel video, looped, no sound; 4 paper cutouts. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad.

In a catalog essay for Raad’s 2015 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, curator Eva Respini describes his practice as responding to Jalal Toufic’s assertion that traumatic social ruptures, like war or revolution, leave artworks “extant but not available,” severed from the now-decimated meanings and associations and affects to which they had been tethered. The role of the artist, for Toufic, is to lure meaning back, to pull it out of withdrawal. But how? Raad seems to know words and images aren’t up to the task—they are as fickle as those falls, as flat and flimsy as those dolls, and he knows that his attempts to pull memories, feelings, or even, sometimes, shadows out of hiding will end up with results as erratic and insecure as history itself, which he understands as an endlessly rewritten fiction.

Toufic’s severed artwork could be the conceptual motor for Scratching on things I could disavow, which wonders at mysterious phenomena humming like electrostatic around artworks when they transfer between institutional contexts. Now they are doubly dislocated, cut from their pasts, moved by money that funds both wars and art worlds into dissonant cultural frames. Raad finds these dislocations literally maddening. In a performance-lecture at the MoMA retrospective, he told a story of an Arab man involuntarily institutionalized in a psychiatric ward after running into a wall when he tried to enter a museum. Raad has said he felt like he was losing his mind when he noticed the absence of shadows in that museum in Beirut.

Walid Raad: We have never been so populated, installation view. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad. Pictured: Walid Raad, Epilogue: The Gold and Silver, 2021. 10 pigmented inkjet prints, 23 3/4 × 20 1/2 inches each.

Adjacent to the shadow traps is a second room, enrobed in a plushly textured maroon-colored wallpaper, which houses Epilogue: The Gold and Silver (2021). This two-tiered grid of ten pigmented inkjet prints displays sumptuous precious-metal objets d’art that Raad claims he discovered in a private collection in Amman, each crawling with a specific type of insect (ants on one, spiders on another, stick bugs on a third) with a Buñuel-esque creep. Across the room is a thick and uneven, Salon-like arrangement of Epilogue II: The Constables (2021), fabled photos of nineteenth-century cloud paintings allegedly discovered on the backs of seven out of 131 Old Master works acquired by the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Raad says they were found when an art restorer, “the best . . . of her generation,” first X-rayed them after the Louvre’s acquisition. The museum has since forbidden further inspection of the works or for anyone to see their fronts, or even for them to be displayed—their photographs (pocked with color swatches, barcodes—the signifiers of museum administration) must serve as proxies. Bluntly dissolving museological certainty, the wall text concludes: “So, who did this? We don’t know. Are they Constables? We don’t know. Why clouds? We don’t know.”

Walid Raad: We have never been so populated, installation view. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: Steven Probert. © Walid Raad. Pictured: Walid Raad, Epilogue II: The Constables, 2021. 7 pigmented inkjet prints.

“We don’t know” may be the motto of all of Raad’s works, whose narratives are motivated by nonfeasance and whose appearance admits their own fakery: the bird prints are obviously designed and printed, not even pretending to be the “actual” artifacts; on second glance, the patterned wallpaper is only a simulation of opulence; the shadow-trap paintings, executed as they are on the surreally smooth support of the cheap wood substitute MDF (essentially, sheets of compressed dust), look like digital stickers. It’s an exhibition that’s a diorama of itself. All these instabilities in appearance and knowing, these derangements of contexts and meanings and histories, form a thesis of art itself as failure, the institutions in which it circulates a closed circuit of insanity. Where’s the meaning? We don’t know.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.