Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

From Mozart in a mall to Carnegie Hall: a pianist’s memoir

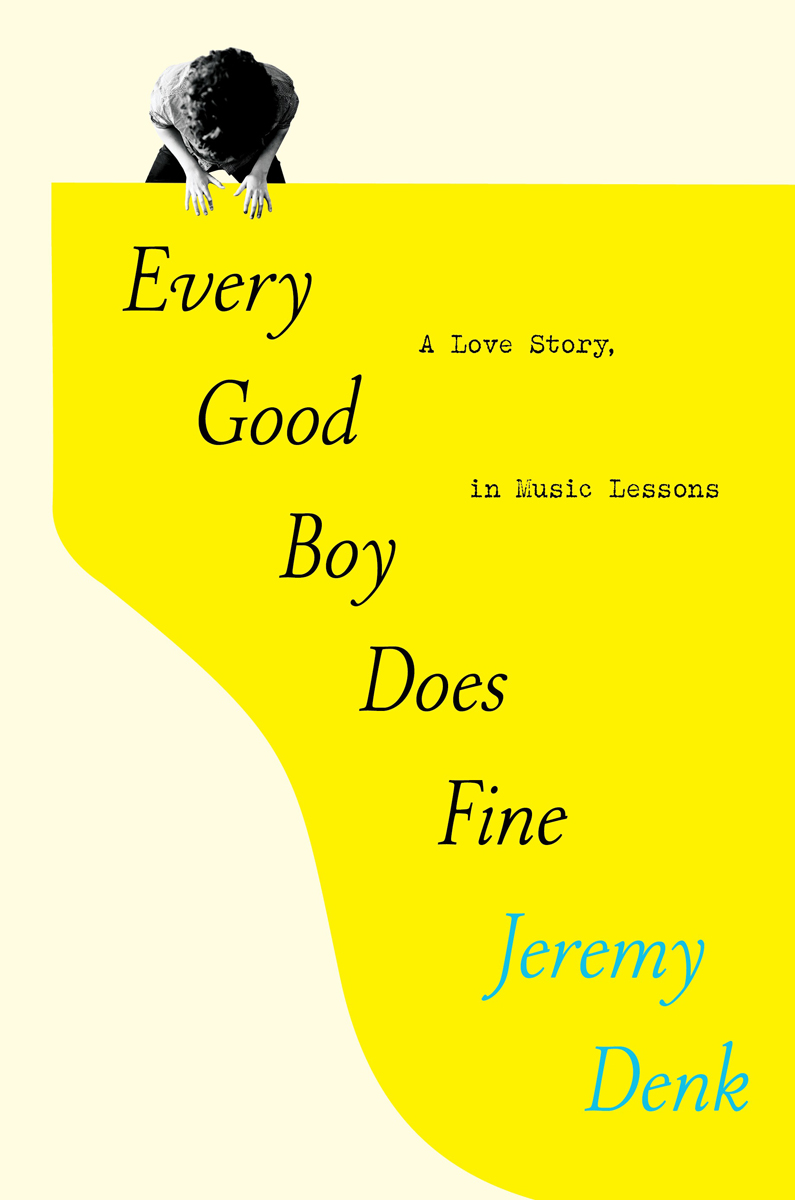

Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons,

by Jeremy Denk, Random House, 368 pages, $28.99

• • •

I still vividly remember the piano lessons I took in the early 1990s. My teacher, who grew up in the Soviet Union, told me that practicing was all about suffering, but that one must suffer to reach the reward. I loved playing piano, but hated practicing, with its grinding repetition, dreary scales, and robotic Hanon études. Once, as I was ably sight-reading my way through a Mozart passage, she stopped me abruptly. “You are lucky that you are naturally good at sight-reading,” she said sharply, “but I can tell that you have not been practicing this piece.” At age fourteen, after I played a Chopin nocturne at a recital, she admonished, “This is technically very good, but your problem is that your heart has not yet been broken. You will play Chopin with more feeling once your heart is broken!”

In Every Good Boy Does Fine, the noted pianist Jeremy Denk has penned a unique memoir. It is partly about his own life—a coming-of-age story refracted through the power of music—but it is also about his many years of lessons, and his teachers. Most popular narratives about music center on the finished product—the triumphant concert, the celebrated album—but Denk focuses instead on the far-less-glamorous process of becoming. It is a book, he writes, about “a love for the steps, the joys of growing and outgrowing and being outgrown.” In addition to being an accomplished performer and musician, Denk is one of the most articulate writers on classical music working today; he maintained a blog for many years called Think Denk and has contributed essays to several publications, including the New Yorker.

The memoir begins hilariously with Denk’s first major breakthrough, via a purchase at a mall. “When I was twelve, I went to the record store in the new mall and smeared what was left of my slice of Sbarro’s pizza all over every last item in the classical aisle,” he recalls. He has his first musical epiphany listening to the cassette of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante he procured there. A series of trills materializes that transcends mere ornamentation, seeming to float in midair. “The growing, climbing notes were mapping onto me, everywhere, rising in my chest, changing my breath, and in the balls of my feet, making me stand on my toes,” he writes. “I was no longer receiving music from without, but being filled from within, like a balloon. The feeling was so intense that for once I didn’t have time to overthink.”

Such subjective experiences are difficult to document, and Denk does so memorably and passionately. But he soon gets bogged down in the humdrum details of his early family life, in dull, plodding passages that read like they were no fun to recount, but were there to fulfill the brief of a memoir. Every Good Boy soars back when he discusses music, in pages brimming with enthusiasm, energy, and humor. I chuckled at his description of the sonatinas (shorter, lighter, easier sonatas) by composer Muzio Clementi, the bane of every beginning piano student’s existence. “They follow a formula: You start with a cheerful tune and then play some scales, wrapping things up with the classical equivalent of ‘jazz hands,’ ” he remembers. “At the beginning of the second half, you get one semi-surprising shift, as if the piece were about to become interesting. This is just a decoy—soon you have to play the same dippy tunes and scales all over again. Sonatinas could be considered instruments of torture, despite and because of how happy they seem.”

He quickly exceeded that form’s cloying grasp, ascending the ranks to become a serious concert pianist by way of training at Oberlin, Indiana University, and Juilliard. Denk had several well-known professors, notably the late Hungarian-born pianist György Sebők, who taught at Indiana. Denk explains the subtleties that Sebők imparted and his enigmatic maxims, which possessed a Yoda-like wisdom. “Some notes are up, and some notes are down,” Sebők reportedly said while discussing slight wrist movements and their meanings. “Don’t play against gravity.”

Great performances are built around these fine nuances, and much of the book chronicles a long quest to get inside classical music, to understand it. In one example, an incidental lesson from the pianist Boris Berman at the Ravinia Festival leads to a “radical revelation,” Denk remembers, on “how the smallest timbral choices invoked vast and deep dualisms of life, heavy and light, light and dark, individual and mass. The way you controlled your fingers’ journey into a key, the degree of attack and release and follow-through, could make a chord feel drawn to the sky or barely able to lift its feet.” The reader develops a deep appreciation for all the small things that musicians do to make the work come alive. Sheet music and recordings are only a few pieces of the puzzle; classical music’s spirit is in the live performances, and in the musicians themselves.

Chapters on melody, harmony, and rhythm are interwoven with personal reminiscences, hand-drawn musical diagrams, and analysis. In a way, it is many books in one, and therein lies some confusion. Every Good Boy balances somewhere between an autobiography, a collection of teachings, and a more general discussion of working in classical music. Though it is arranged chronologically, it is sometimes choppy, lacking the flow of a cohesive narrative or the character development that would help us connect with the myriad musicians, family members, and other people who come and go in the story. One of the best segments is actually the appendix, which is densely packed with colorful, healthily opinionated descriptions of the pieces of music mentioned throughout. Perhaps because of the lack of editorial pressure—it’s the appendix, after all—it has the joy and looseness that can be missing elsewhere. While Every Good Boy Does Fine may be imperfect, it’s also an honest and profound immersion into the reality and artistry of performing classical music.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.