Brandon Taylor

Brandon Taylor

No winners here: in A. M. Homes’s new novel, a wealthy Republican family navigates a game of power and dysfunction following

the 2008 election.

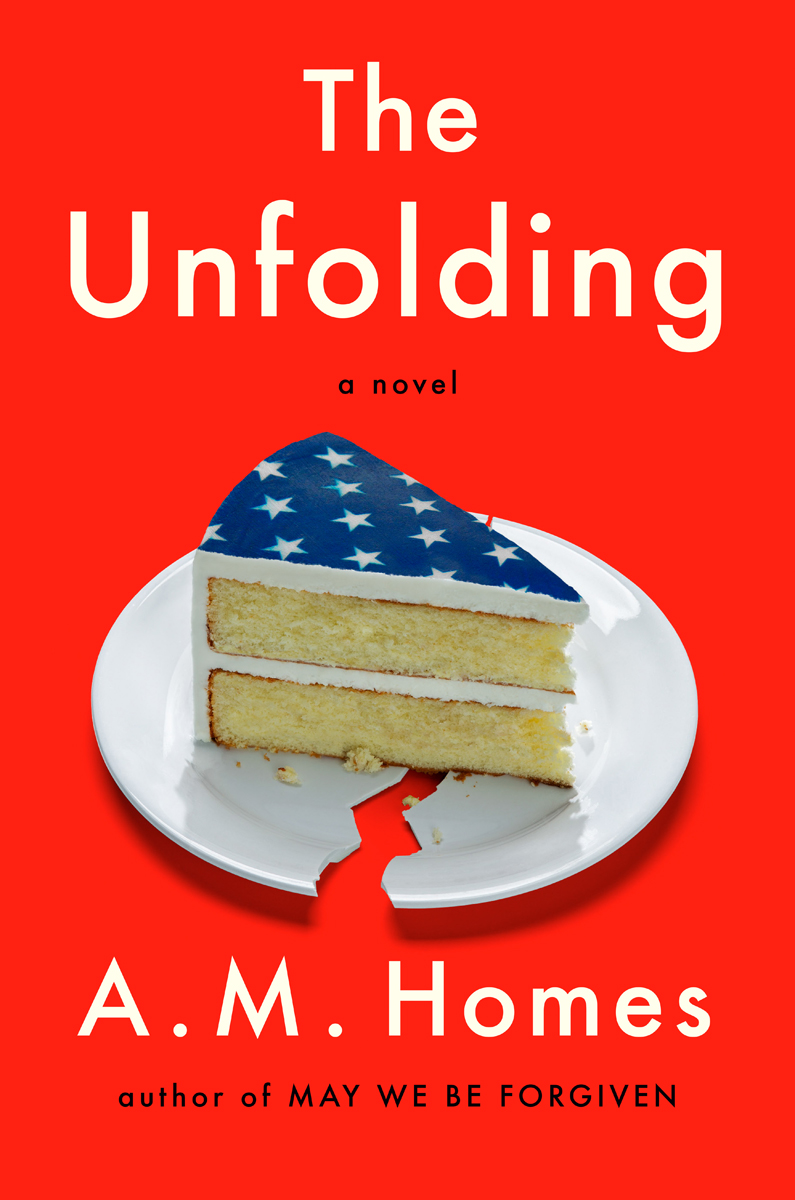

The Unfolding, by A. M. Homes, Viking, 396 pages, $28

• • •

There is a good, though not excellent, short story hidden somewhere in the four hundred pages of A. M. Homes’s The Unfolding, which, in flashes, is a charming pastiche of The West Wing meets Married with Children. Or maybe, given the amount of pithy Sorkinian patois, you could carve out a couple passable SNL sketches about the electoral politics of 2008. But on balance, The Unfolding is depressingly shallow, arriving too late and with too little intelligence, humor, wit, or insight to be useful or entertaining.

The plot is simple. We encounter the Big Guy on the evening of the 2008 presidential election as he commiserates with fellow McCain supporters. The Big Guy then sets about assembling a kind of think tank to “take back America,” so to speak. Meanwhile, his wife, Charlotte, is desperately miserable and struggling with substance use. His daughter, Meghan, is eighteen and quickly starting to realize there is more to life and history than she’s been taught by her father. We follow the family in the days, then weeks, then months after Obama’s victory. Some chapters are hours apart in chronology and others retell incidents from alternate perspectives. The structure—dilating and contracting across a narrow band of time—works best in subtly paralleling personal and familial breakdowns with national upheaval, but at its worst, the form makes this novel feel interminable.

The Big Guy gathers his fellow malcontents to scheme. Except, get it, they’re kind of losers, these old dudes. They ramble, nod off, and bicker as they try to put together an organization that will thwart those dastardly Democrats. The first shadowy conclave, convened in Palm Springs four days after the election, is funny and sad. As the men grumble and complain about their loss of relevance and centrality in the national narrative, Homes plays the scene with deft irony:

“It was clear to me that a mockery had been made of the system that had for two hundred years anchored the land of the free, home of the brave.” The Big Guy’s voice crescendos as he reaches the word brave. “In the past there were times when I thought it didn’t really matter which side a man was on as long as he loved America. Being in that hotel room on Tuesday, listening to men speaking in platitudes, was a night unlike any other. It was the long goodbye, the end of not just an era but of the America as dreamed by our fathers.” The Big Guy’s eyes mist, like he might actually cry.

The later conclaves are essentially the same, to diminishing effect. Homes is dedicated to the idea of these men as so pickled by their own vice and privilege that there’s not an intelligent thought to be found among them. They remain static in their grumbling and their vague schemes, which prevents the irony from deepening or sharpening its critique. What ought to be a central driver of the plot or the evolution of the novel’s themes becomes an inert gimmick.

It can only hurt a novel, even a satirical novel, if the author deprives their characters of the conviction of their beliefs and the shape such convictions can give a personality, a circumstance, a life. This is not endorsement. This is, as D. H. Lawrence says, moral writing. Homes trades away her characters’ convictions and depth for attempted comedic effect. No contrast. No pathos. These men are hollow, which makes the story itself hollow.

More expertly drawn is Meghan, the daughter. Her whole life, her father has made a big to-do about history and America and the civic duty of its citizens. Yet, when she votes for the first time, she feels a disquieting anticlimax that grows to a genuine sense of unease as she watches McCain lose. When the funereal pall falls across the ruined celebration at the hotel in Phoenix on election night, it lingers in the mind mainly because we share in Meghan’s loss of innocence. Back at boarding school, she is restless—something feels off. A late-night swim with a mysterious stranger at the hotel and an unnerving conversation with a cab driver have wedged something loose in her world view. Like many young people whose lives have been managed, Meghan has tasted the first bitter notes of disillusionment, and she is not coping well.

The Unfolding is most alive when it plumbs Meghan’s itchy awakening into herself. In one of its best scenes, she calls the police to help an injured deer:

Meghan steps back, giving the officer room. As he goes closer, the doe tries to lift its head. Meghan thinks it’s sweet; the doe is grateful for the help. The officer fixes his flashlight on the doe’s face. Before Meghan can say or think anything, his gun is out of the holster.

Bang.

The gunfire startles Meghan’s horse, and she chases after him. The police form a search party to find her. She bickers with the cops, then gets fed up:

She calls Tony. She calls Tony because that’s what her parents would do. Whenever they are overwhelmed or in over their heads, they call Tony. That’s what best friends are for. That’s what fixers are for—repair work. Tony does the repair work for the White House.

It’s in that moment we realize this young woman is coming to more than one kind of awareness. Both that the world is more complicated than she thought and also that she has actual power to wield against those who get in her way. It’s a chilling likeness to her father, and had this moment come, perhaps, at the climax of a short story, then it would be moving, dark, and implicating. But here it is just character development that gets lost in the flow of pointless detail.

Homes for some reason describes any surface or object that comes into contact with her characters as though she were writing about the contours of the human soul. Do we need to know what the taxi seats feel like? What the barn smells like? What the people at the voting center are dressed like? These are what I call fake details. In that they do not matter. They offer no insight, just a gesture toward insight.

I was bored by this book. By its lazy stances, its lax politics, and its rote writing. The notion of American politics as a kind of entertainment starts out as an interesting observation, but by the seventh metaphor relating some aspect of the political process to an arcade or slot machine, the charm has long worn off. It’s like Homes had one idea—America’s power structure is a game played by the rich and privileged—and couldn’t get beyond its immediate appeal to actually embody either the game or the consequences.

Very seldom does the novel pulse with life—it’s only in those moments with Meghan, who by the end of the book has become a fascinating study in familial indoctrination and disillusionment both, that this story truly unfolds.

The rest is just boring.

Brandon Taylor is the author of the novel Real Life and the story collection Filthy Animals. He lives in New York.