Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

Other voices, other pleasures: a film series looks back at queer cinema from 1965 to 1996.

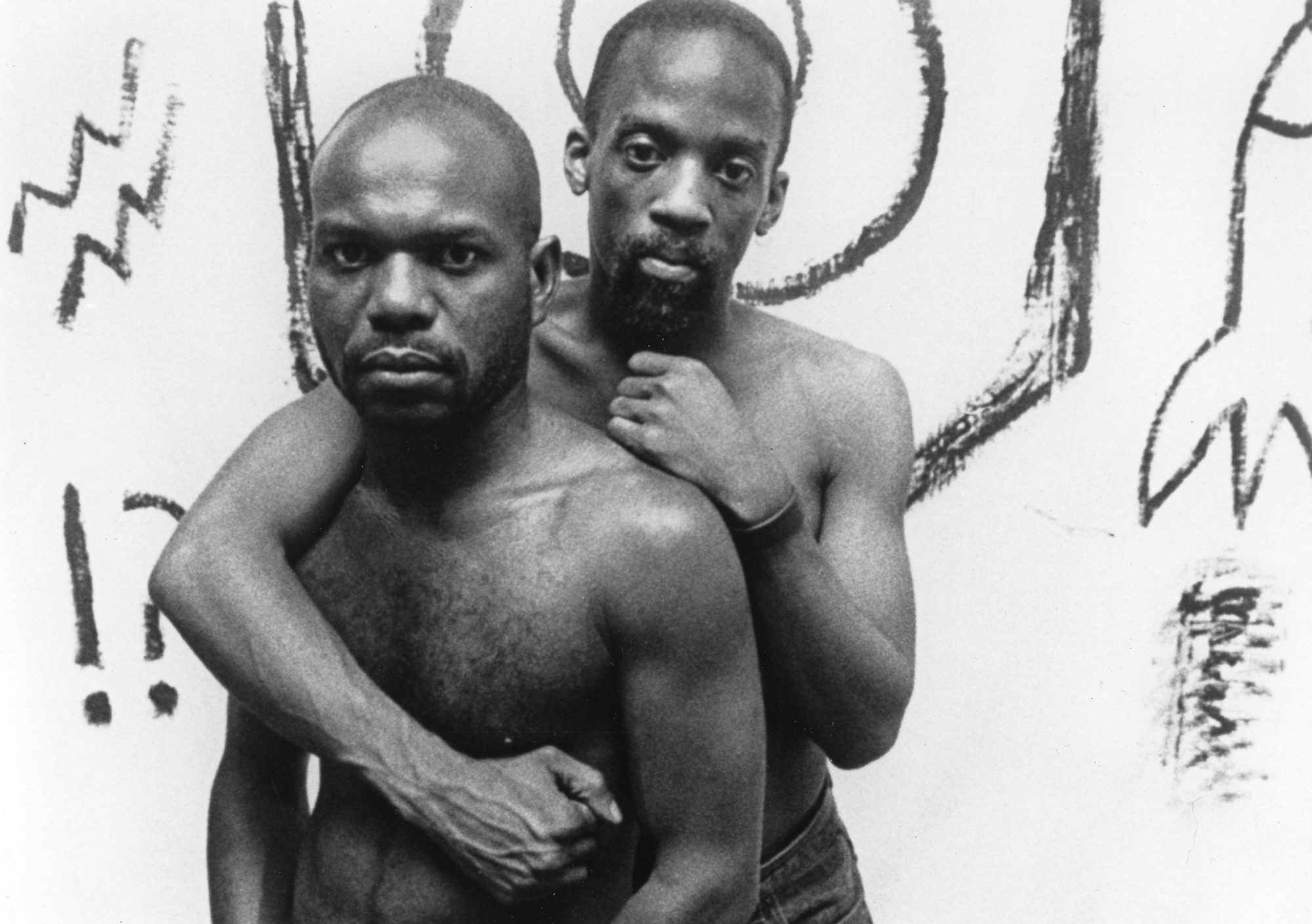

Tongues Untied, 1989. Directed by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy Photofest.

“ ‘Now We Think as We Fuck’: From Queer Liberation to Activism,” organized by Carson Parish, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, January 28–February 5, 2020

• • •

The title of the Museum of Modern Art’s upcoming retrospective of queer cinema sounds like a declaration of sexual and intellectual liberation. Now we think as we fuck—which is to say, freely, outside norms, with mind and body conjoined in imaginative acts of desire, fantasy, pleasure. In fact, it is a line by poet Essex Hemphill, spoken in Marlon Riggs’s essential video essay Tongues Untied (1989), evoking the paranoia that invaded sex in the first decade of the AIDS crisis: “Now we think / as we fuck / this nut / might kill us.” Toward the end of Riggs’s personal yet polyvocal account of what it is to be black and gay, during the final minutes of a work by turns playful, angry, and gorgeous, Hemphill delivers his verse to the camera. Thinking intrudes, unwelcome, so much coldness on heat. Now that fear has driven him away from encounters with “tall dark strangers,” Hemphill relates, “We return to pictures. / Telephones. / Toys.”

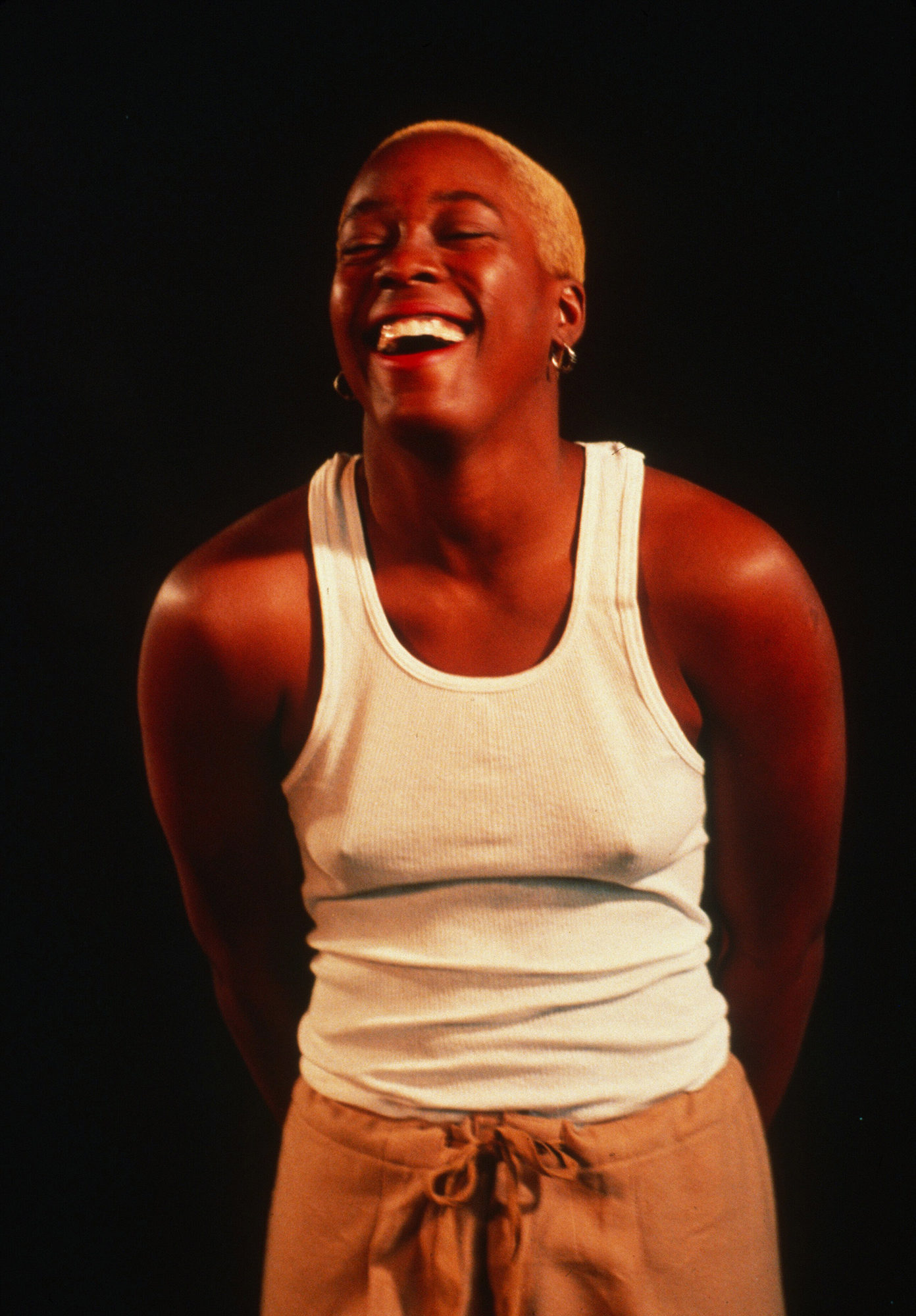

The Watermelon Woman, 1996. Written and directed by Cheryl Dunye. Image courtesy Photofest.

But what pictures were there to find? Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) goes looking, only to suggest that when it comes to black lesbian presence in the cinema, the archive is riddled with such gaps that fabulation is the best response. Like that of Riggs, and like that of so many of those included in “Now We Think as We Fuck,” Dunye’s vital work was created in response to missing images, unjust images. Undertaking its own return to pictures—specifically to twenty-two films and videos from the MoMA archive—the series presents a selection of such efforts as they were manifest in the United States between 1965 and 1996. (One non-US film is included: Laurie Colbert and Dominique Cardona’s Canadian documentary Thank God I’m a Lesbian, 1992.)

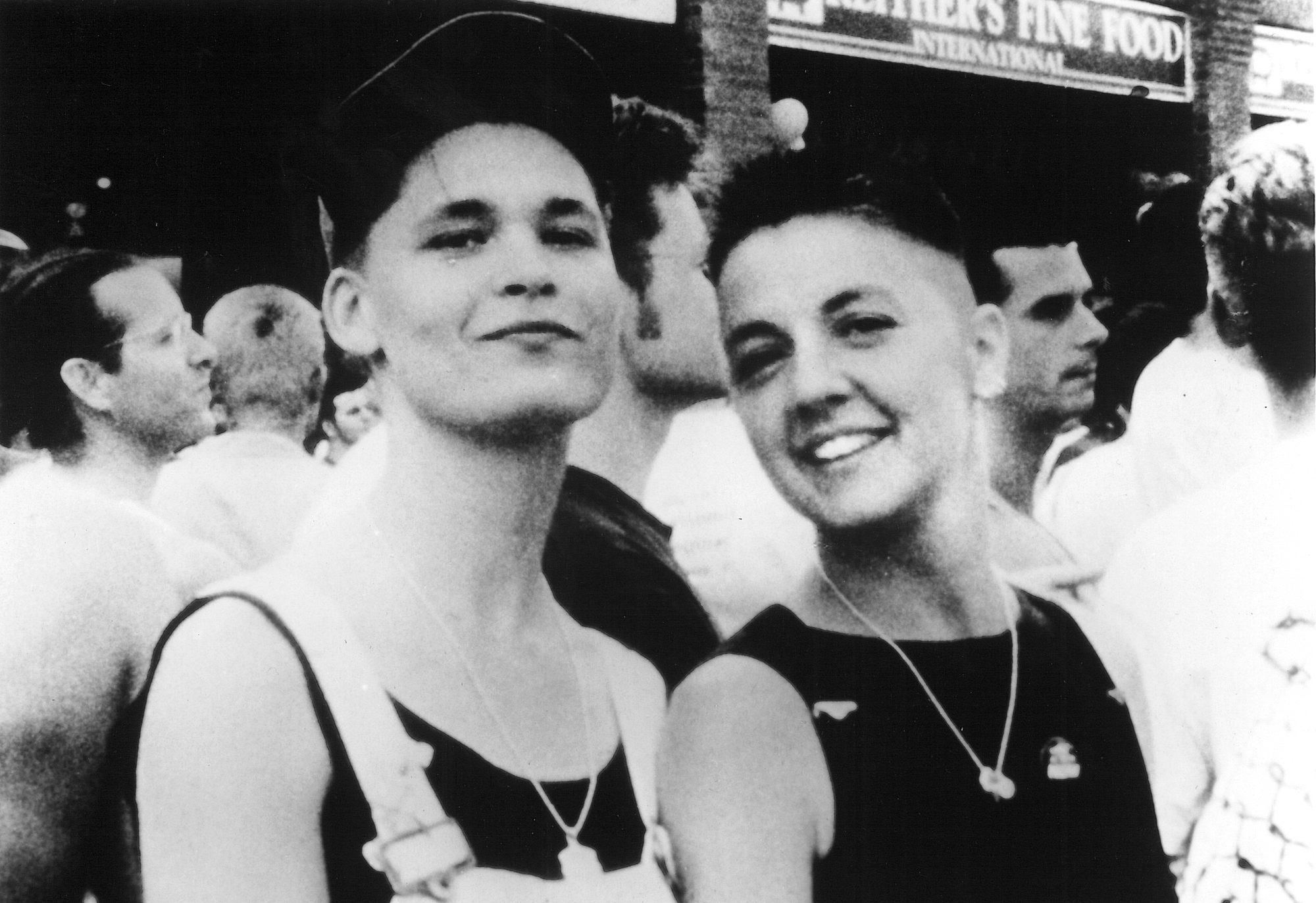

Thank God I’m a Lesbian, 1992. Directed by Laurie Colbert and Dominique Cardona. Image courtesy Women Make Movies.

The twin associations of the series’ title—freedom and constraint—course throughout the chosen works. Stemming from various artistic and activist contexts, and providing ample evidence of their intersection, these films and videos are situated at the conjunction of visual thinking, living, and fucking. Breaking ground in the representation of historically marginalized subjectivities and sexualities, they exist on a spectrum extending from a strong commitment to formal experimentation (shorts by Barbara Hammer) to talking-head documentaries that prioritize the clear communication of personal testimony (the Mariposa Film Group’s Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives, 1977) and activist tapes (the safer-sex video Chance of a Lifetime, made by Gay Men’s Health Crisis, 1985). Across it all, the moving image is turned against the narrow repertoire of representations that prevailed in commercial cinema and television, toward other voices, other needs, other pleasures.

Parting Glances, 1986. Written and directed by Bill Sherwood. Image courtesy First Run Features.

Despite this emancipatory ethos, Hemphill’s invocation of risk is never far away. Rather than framing queer liberation as a matter of uncomplicated optimism or growing acceptance, the series frequently attends to divisions within the queer community and the differential distribution of vulnerability and marginalization among its members. Unsurprisingly, these perspectives are most present in diverse works made in relation to the AIDS crisis, not only Tongues Untied, but also Gregg Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), a diaristic video that reflects on living with the virus, and Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances (1986), a narrative dramedy boasting a young Steve Buscemi as a seropositive musician lovingly ministered to by his ex-boyfriend. Parting Glances entertainingly renders the queer everyday of creative-class Manhattanites, but even here, in what is as close as the program comes to conventional fiction filmmaking, Sherwood makes no bid for assimilation. Jean Carlomusto’s Doctors, Liars, and Women: AIDS Activists Say No to Cosmo (1988) captures the ACT UP Women’s Committee in the midst of their first action, taking aim at misinformation published in Cosmopolitan magazine and frankly confronting the gendered, classed, and racialized determinations of who counts as an authority and who is given a voice, both in the movement to fight AIDS and in the public sphere at large.

First Comes Love, 1991. Directed by Su Friedrich. Image courtesy the artist.

It would be not be wrong to understand “Now We Think as We Fuck” as structured around the rupture of AIDS, parsing queer life into a carefree before and an anxious after. Yet revisiting these films and videos while Mayor Pete is on the campaign trail, when homonormativity is a formidable cultural force and the demand for “positive” images still feels inescapable, I found it striking how many of them, from the very earliest through the plague years, challenge the attitudes and exclusions of respectability politics in ways that remain meaningful today. Running across the historical break of the epidemic is a continuous demand for the right to difference, to live otherwise. Even in Su Friedrich’s First Comes Love (1991), a 16mm short that ostensibly advocates for marriage equality, the equivocation concerning what it would mean to participate in such an institution—in such a spectacle—is palpable. Taken together, the films and videos of “Now We Think as We Fuck” underline the value of communities representing themselves to and for themselves—in all their messy ambivalence, replete with ugly feelings and disagreements.

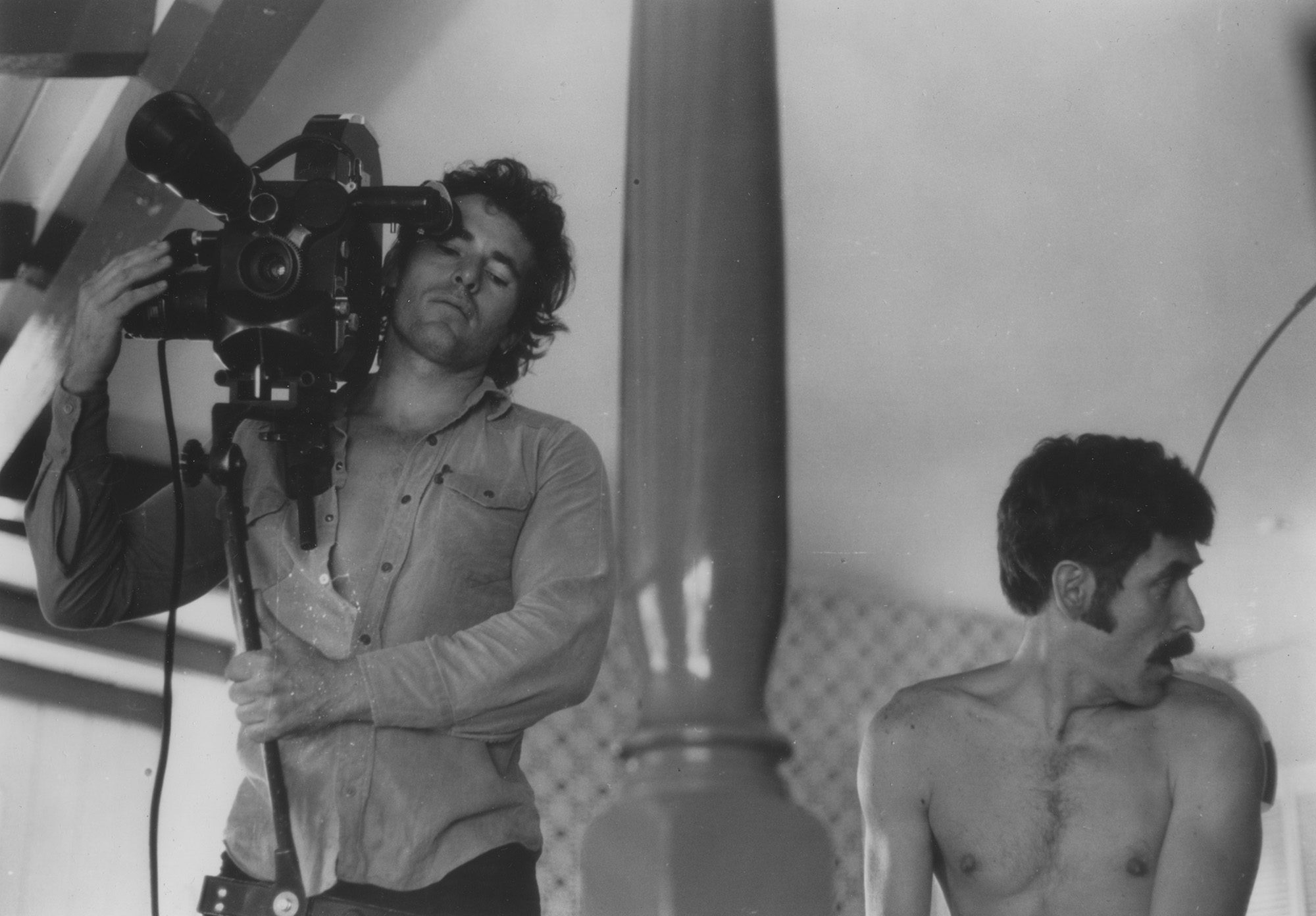

Sextool, 1975. Directed by Fred Halsted. Image courtesy Curtis Taylor and MoMA Film Archives.

Nowhere is the affirmation of alternative sexual practices more evident than in the three films that deliver most on the hardcore action promised by the series’ title: Fred Halsted’s sadomasochist classics The Sex Garage (1972), L.A. Plays Itself (1972), and Sextool (1975). These films start from the assumption that pleasure and danger are intertwined, and that sexuality is invariably bound to risk, albeit in ways and to degrees that change depending on the context. When screened at MoMA in 1974 with the filmmaker in attendance, L.A. Plays Itself drew protests outside from gay-rights advocates who objected to its depiction of homosexuality and, in particular, the fisting sequence that concludes the film. I can only wonder what they would have made of the riveting centerpiece of Sextool, a gangbang of a blond sailor on a bare metal bedframe. Seen now, these films offer not only glimpses of a lost Los Angeles and a titillating hint of what truly experimental pornography can be. Like many in the series, they stake out just how vast the distance is between today’s gay mainstream and a different dream of emancipation—one still unrealized, yet thankfully still alive.

Erika Balsom is the author, most recently, of An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea, published in 2017. She is a senior lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London and writes criticism for publications including Artforum, frieze, and Sight & Sound. In 2019, together with artist Éric Baudelaire, she was awarded an UNDO Fellowship from Union Docs.