Eric Banks

Eric Banks

Kathryn Scanlan presents a captivating glimpse of the strange, small world of horse racing.

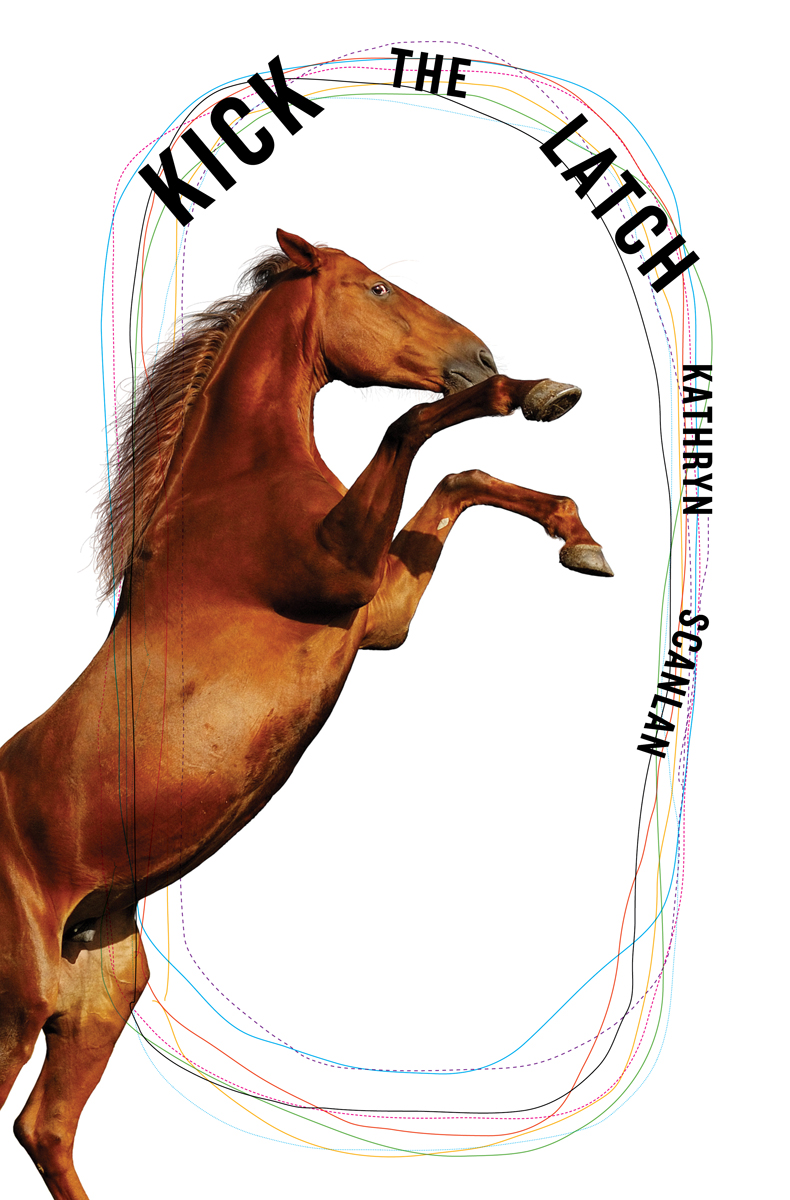

Kick the Latch, by Kathryn Scanlan, New Directions, 129 pages, $17.95

• • •

The vignettes that make up Kathryn Scanlan’s horse-racing anti-epic, Kick the Latch, are models of compression. Kick them indeed and you imagine them snapping back with deadly spring-loaded force. The longest mini-story here, “Bicycle Jenny,” which packs in the biography of an oddball chihuahua hoarder, strains to reach four pages. The briefest, “Racetrackers,” comprises a single sentence: “You’re around some really prominent people and some are just as common as old shoes.” Both are miniatures in a miniature, sprightly nuggets (much like the book itself), daring to capture the arc of a life or the flavor of the track in the tightest number of strokes possible.

Ostensibly crafted from transcribed interviews with a female veteran of the hardboot midwestern racing circuit, which were then edited down to the glistening bone, Kick the Latch is a fitting third act for Scanlan. With her recent collection of stories, The Dominant Animal (2020), she staked her place in the minimalist lineage that went underground for years like cicadas only to burst out magnificently in the work of such stylists as Diane Williams, whom Scanlan often credits as a touchstone. Attuned in particular to states of uncanny and vulnerability, Scanlan’s stories hold a special place for furry creatures (a rabbit hatch is never just a rabbit hatch in her fictional universe). Her first book was the uber-minimal Aug 9—Fog, which reworks the terse entries of an eighty-six-year-old’s diary that Scanlan happened upon at an Illinois estate auction. A page chosen at random gives the flavor: “D. washed my head. Fed all my flowers. No dogs in sight today.” Remarkably, what seems a formalist game yields an almost elegiac blossom that makes the reader starkly aware of the passage of time (what is a diary?) and the quiet dignity of its original author (what is a life?).

Kick the Latch braids the divergent strands of both books. Sonia—we never learn her last name—was a pipsqueak when her love affair with horses pulled her into the grits-and-hard-toast world of cheap midwestern ovals and mostly broken-down claimers. “I was known as the Coca-Cola kid because everyone wanted to buy me a drink, get me drunk, but I’d ask for soda instead.” She badgered her way onto the backstretch with her gumption for hard work and an intimate connection to horseflesh: “If your parents don’t get along, if they argue, if there’s an abuse situation, you’ve got your horse. When things were bad I’d go to the horse and the horse would always make it better. That’s why I always say my horse raised me.”

Sonia finds herself in the rare position of a woman working her way up from mucking stalls to calling the shots in the barn. She greets the dreary conditions with scrappy, often amusing equanimity. Dilapidated trailers that leak “fucking bucket bucket bucket”; deadbeat boyfriends; constant, backbreaking work (“A jockey took me out to a movie once, but I fell asleep in the first ten minutes”)—all this, and the violence too, somehow pales against the wonder and camaraderie of the strange small world of the track, which she describes with an ethnographer’s touch in a chapter titled “Enough” and which warrants the full pint-size block quote:

The backside is a little city. You flash your track license at the guard shack to get in. There’s an ambulance on the grounds during training hours because people are always getting hurt. Feed dealers sell sawdust, straw, oats, beet pulp, bran, good hay. Tack wagons stock bandages, saddles, medication, leg paints, sweats, freezes, Bowie Clay, sheet cotton, vet wrap. You live at the track, your life is full. You don’t have time to go shopping at the mall. You lose touch with the outside. Things change. You don’t hear about world news unless something major happens, because you’re in your own world and you have enough news.

It’s a closed universe with its own rituals and lingo. There’s alchemy: soda pop slipped in the horse’s water to fool it into drinking, a green substance loaded with belladonna to open up the horse’s nasal passages, Reducine on a toothbrush for a busted hoof. When the grooms get sick, they get shot up with the same antibiotics the vets give the animals. The jockeys are as crazy as squirrels. They pack batteries to jolt their mounts and do anything to keep the weight off (“They get so good at puking they brag about it—I can flip the rice but leave the beans!”). When a jockey wins for the first time, the other riders ambush him and paint his balls with black shoe polish. And they suffer terrible injuries, kicks to the head, shattered bones. You don’t put an ambulance in a story unless you’re going to use it, or a knackering truck. At a track in South Dakota, Sonia recalls that “there was a reservation close by and if ever a gray horse had to be put down, the Winnebagos would come and take off the tail. They’d dye the hair and make it for their costume.” There’s no lack of inhumane (or at least unequine) behavior, but there are plenty of less-bad outcomes as well, and her easy affection for the backstretch is ever present.

Yet so is the violence. Sonia tells the story of her sexual assault (in a one-page chapter called “I Seen Him Every Day”) with the same unsettlingly laconic voice: “He was taking pills. He was a jockey trying to cut weight. He told me he’d just shot a dog.” She’s nearly killed when a horse T-bones her mount; it’s months before she heals up from her broken ribs and punctured lung. When she does, she’s picked up by a big-league outfit in Florida. The trainers wear suits instead of blue jeans, the barns are immaculate, and she’s surrounded by million-dollar prospects rather than the nickel claimers she once managed.

But this isn’t a nags-to-riches story. Somewhere in the transition from the leaky-roof circuit, Sonia loses the thread. “My successes as a trainer and exercise rider were greater at those cheaper tracks. I started to think, Wow—this is it? This is terrible. I don’t want to do it no more.” Life as a civilian—a stint for a time working in a prison near Grant Wood’s resting place (full circle to the Iowa where she first learned to ride), another harrowing experience with a sexual predator—offers a bleak coda to her time as a racetracker.

What’s mesmerizing here is Sonia’s voice, her rhythm and gift for telling a story. You forget for most of the ride that it’s a ventriloquy act and the author—Kathryn Scanlan—wields a mean stiletto for a crop. Bringing together two seemingly antithetical impulses—the authenticity of Sonia’s words, the artifice of Scanlan’s whittled down collage of those words—the book is a nifty feat of equipoise achieved with the same ease that the trainer notes in an ideal jockey who is able to “balance an egg on their back” without losing it. The hybrid that results is a wonderfully empathic window opened onto a fascinating life lived on the margins. “When I tell Jerry stories about the racetrack he doesn’t say much,” Sonia observes at the end of Kick the Latch. “It’s hard for people who haven’t been there to understand.” Scanlan’s neat trick is to give the lie to these finish-line thoughts.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at the NYPL. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.