Hannah Black

Hannah Black

A self-taught artist’s landscapes limn the wild strangeness of memory.

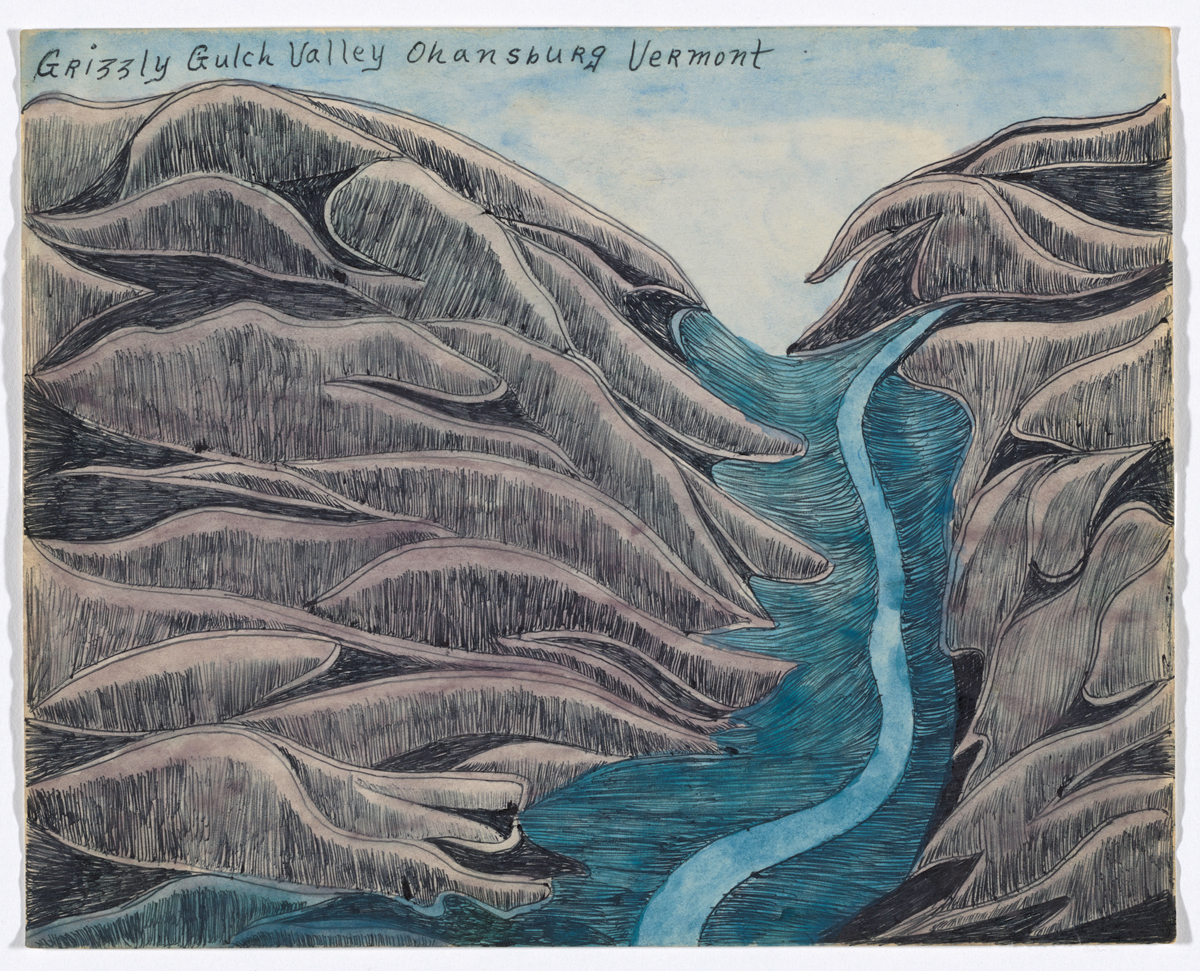

Joseph E. Yoakum, Grizzly Gulch Valley Ohansburg Vermont, n.d. Black ballpoint pen and watercolor on paper, 7 7/8 × 9 7/8 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw, organized by Esther Adler, Mark Pascale, and Édouard Kopp, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, through March 19, 2022

• • •

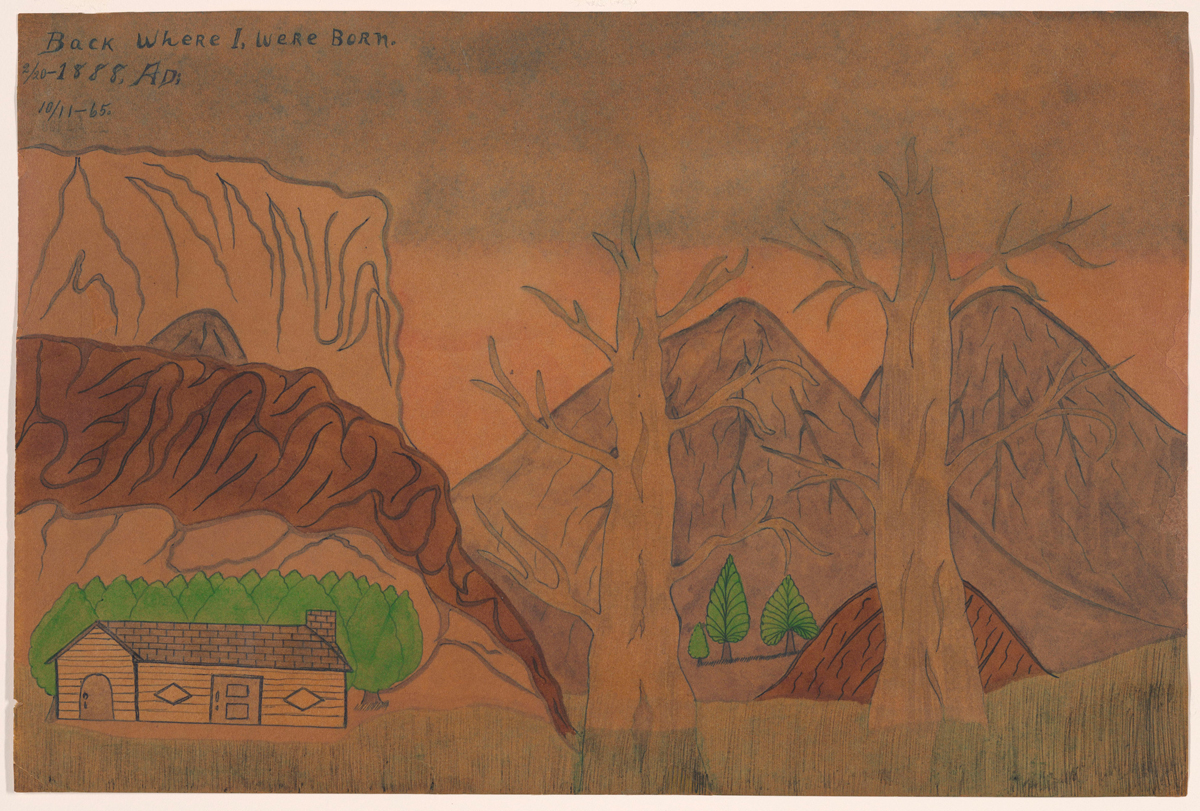

Joseph Yoakum’s art originated in a dream he had in 1962 and resembles the saturated geography of dreams, in which the mind sutures itself together by making a habitat for itself. He was already in his seventies when God appeared to him while he was sleeping and commanded him to draw. Growing old in a storefront studio on Chicago’s South Side, as far in thought from the cultural effusion of the city’s Black Arts Movement as he was close to it in space and time, Yoakum reconstructed the peregrinations of his youth in ballpoint pen and colored pencil. From an early age he had traveled with the circus and the army, systems of entertainment and war, catapulted around the globe by labor and the annihilation of labor. Becalmed in Chicago, he lent new substance to the traces of experience. Across thousands of drawings, a world made consistent by his vision of it took shape.

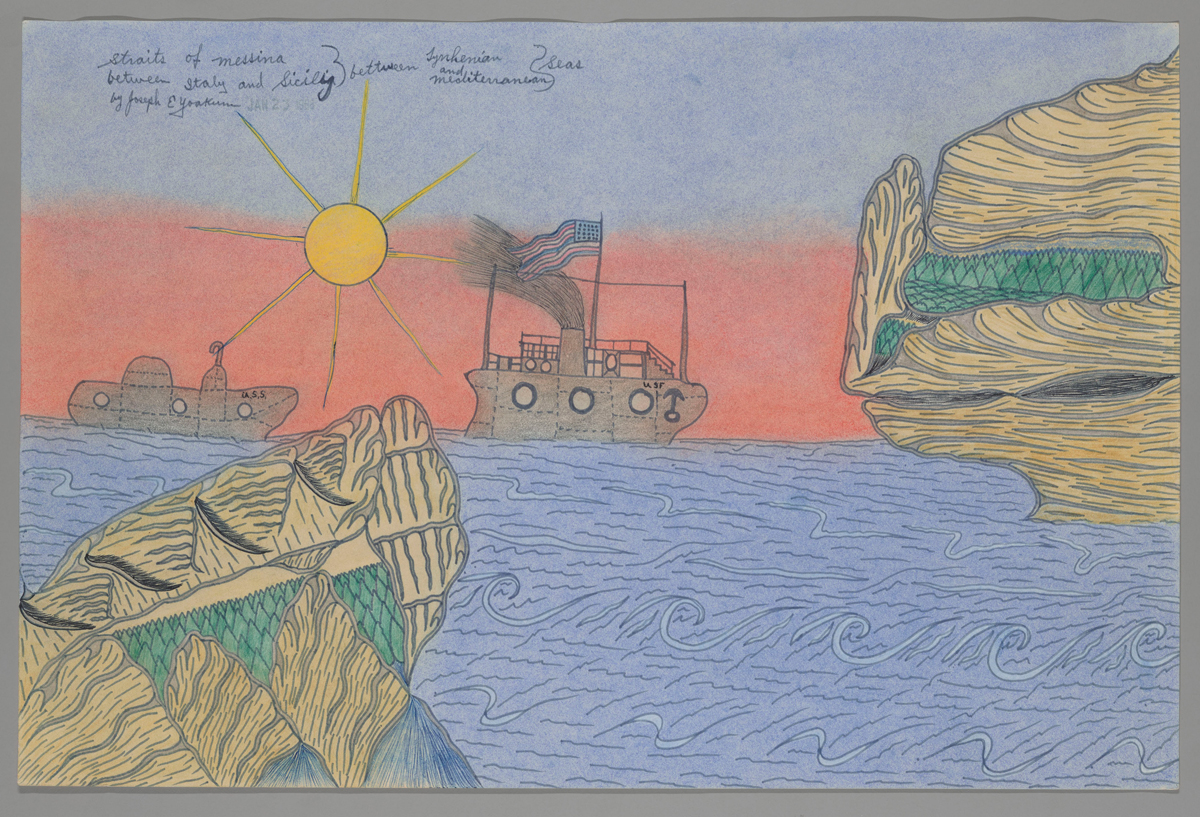

Joseph E. Yoakum, Straits of Messina between Italy and Sicily between Tynhenian and Mediterranean Seas, stamped 1968. Gray felt-tip pen, black fountain pen, blue ballpoint pen, pastel, and colored pencil on paper, 11 13/16 × 17 15/16 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

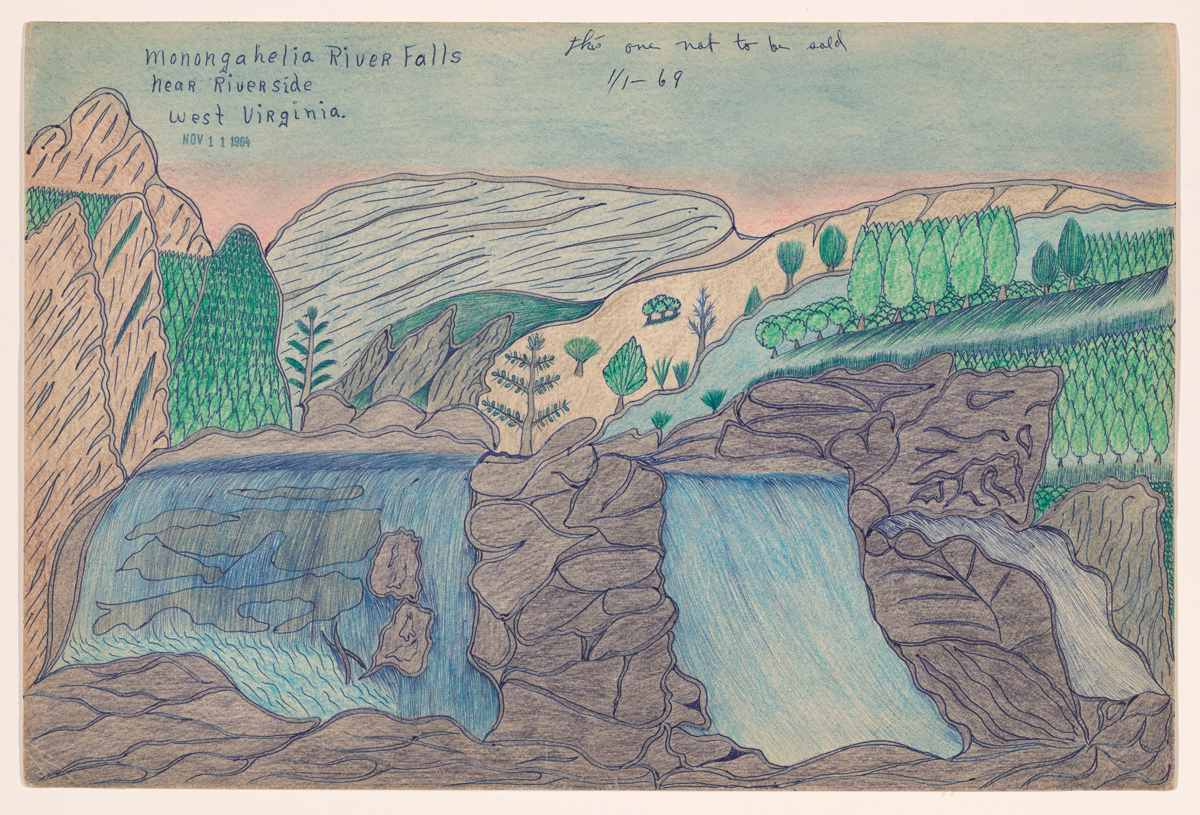

This remembered world evokes the past’s vulnerability to destruction. In Yoakum’s drawings, space as well as time have been abolished. Distance is indicated not by techniques of perspective but by multitudinous trees sprouting thickly in gaps and crevices, sometimes appearing as if enclosed in rock. “Spiritual enfoldment” (sometimes spelled “unfoldment”) is how Yoakum described his process, only accidentally evoking the tightly folded lines resembling innards that make up his hills and mountains. Wherever we are, we are amid the same vegetation and the same ballpoint contours; we are somewhere between the diagrammatic and the ecstatic. Waterfalls in West Virginia, mountains in China, and a red-white-and-blue rainbow over Palestine are rendered with strong lines and soft colors. Saudi and Syrian desert seems to teach him abstraction, like Turner ascending into sky—in Yoakum’s final drawings, produced in a nursing home toward the end of his life, shape and color disaggregate.

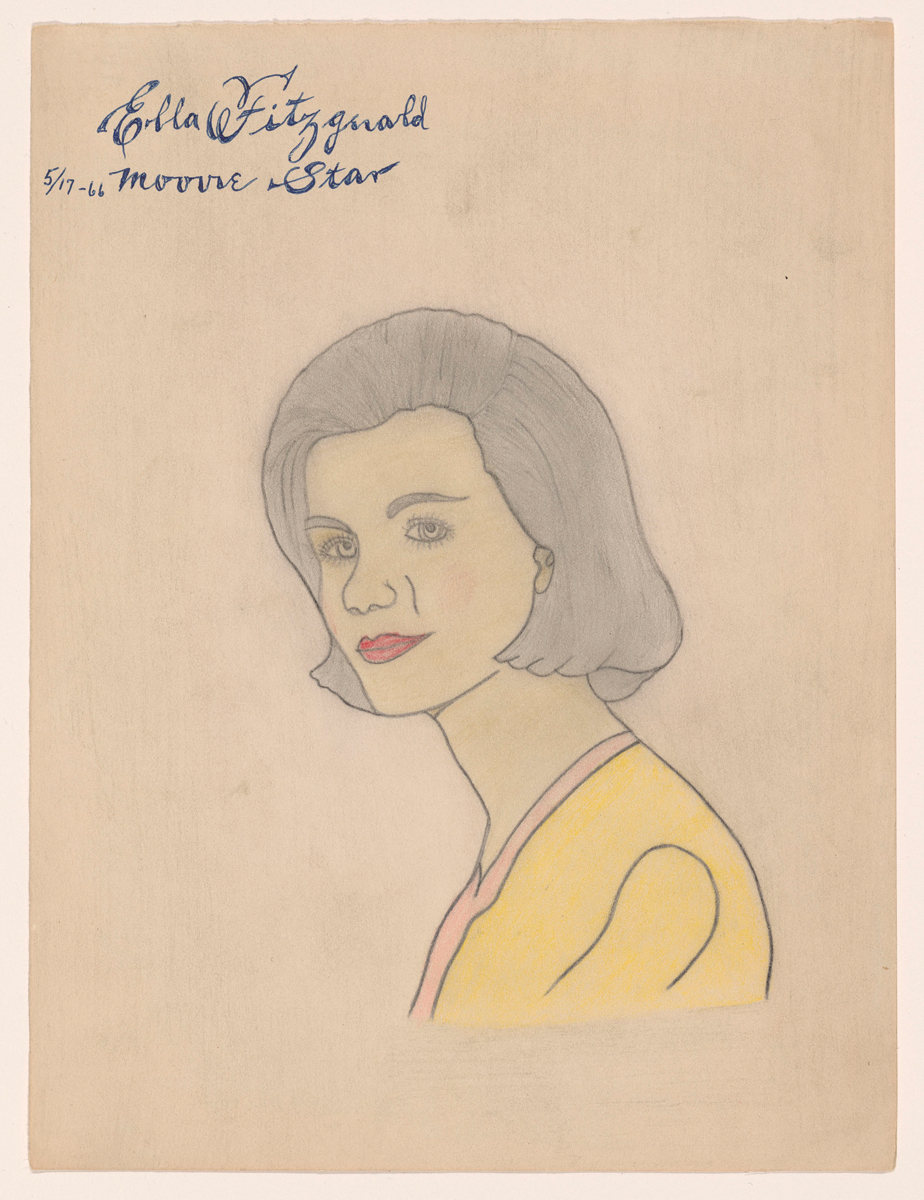

Joseph E. Yoakum, Ella Fitzgerald Moovie Star, 1966. Carbon transfer, graphite pencil, and colored pencil on paper, 11 7/8 × 9 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

Several times Yoakum drew Calvary, the site of Christ’s crucifixion. The word calvary indicates both holy mountain and intense suffering: in either case, compulsory sacrifice. Yoakum was familiar with both. His father died protecting his brother from a white attacker in 1903, and Yoakum found work in a touring circus the same year. It was not the first time: he “ran away with the circus,” as the fugitive phrase goes, for a while at nine years old. While his desire to see the world is not reducible to running away, the human features vaguely discernible in Yoakum’s largely unpopulated landscapes suggest a B horizon of loss concealed by the topsoil of remembered locations. Loss is an attribute of people, not places. The former are, therefore, much harder to render: a little cluster of portraits duly included in the comprehensive MoMA exhibition are clumsy and stiff, though not without the characteristic charm of his line. A portrait of Ella Fitzgerald is copied from a white model in a soap ad; another, of a Native couple in profile, is cliched to the point of bigotry. A politely embarrassed curatorial placard professes to find Yoakum’s racial attitudes puzzling. But he was born less than thirty years after abolition—compulsory sacrifice had not yet been supplemented by compulsory pride. W. E. B. Du Bois saw calvary’s main character in the Event of abolition, embodied by four million newly self-freed people: “Suppose on Michigan Avenue, between the lakes and hills of stone . . . suddenly you see living and walking towards you, the Christ, with sorrow and sunshine in his face?” That was 1863. Though official biography has Yoakum born in 1891, he claimed 1888, perhaps because eight is the luckiest number. Almost invariably, he draws the sun with eight rays emanating from it, like a halo worn by someone who has tasked himself with saving the world from oblivion.

Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Denis Doorly.

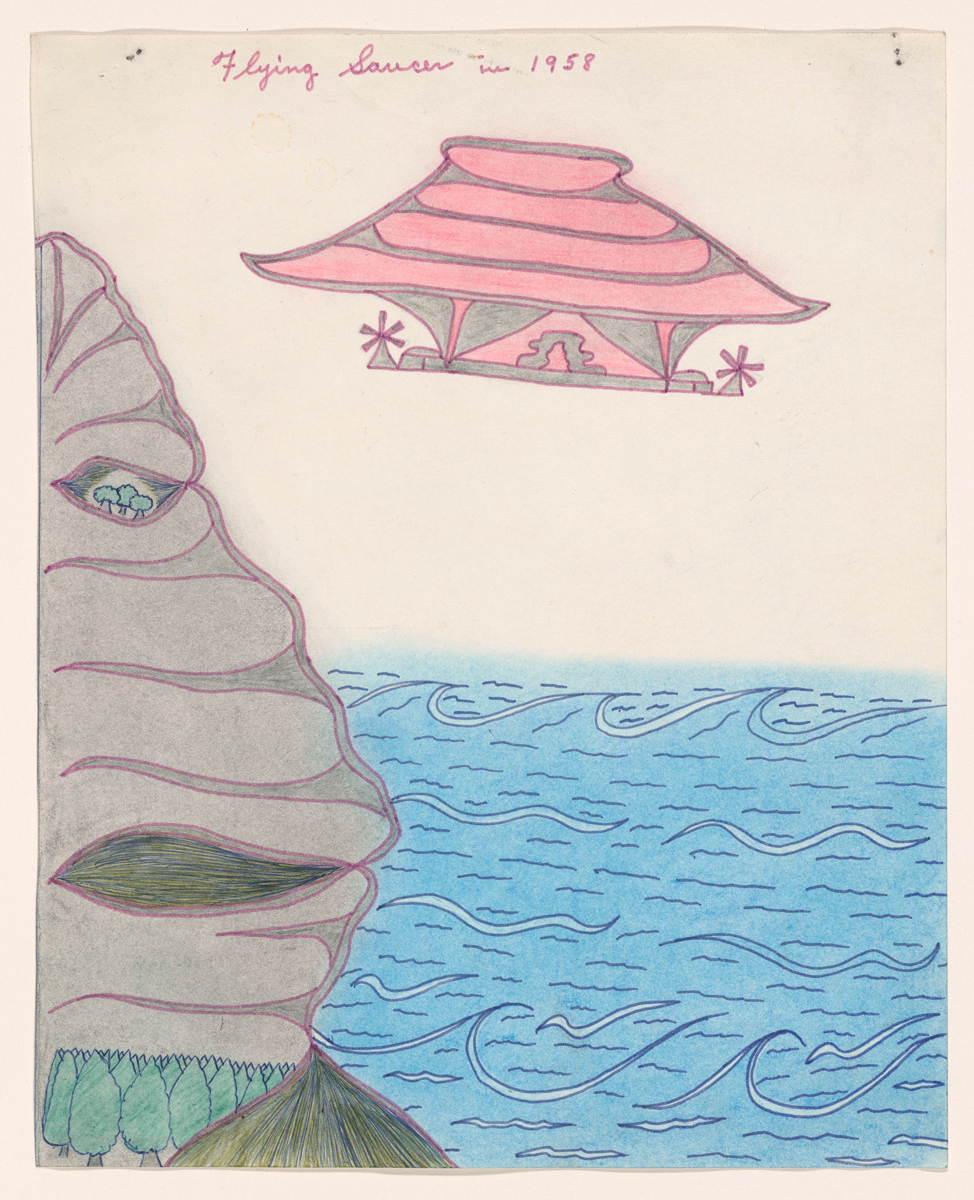

The show is timely: since early 2020 the expansiveness and multiplicity of the world have dimmed and have to be held onto as private belief. The figure of the artist recreating a lost world by hand has taken on additional resonance. But maintaining an image of an absent object risks fiction; some admirers of Yoakum’s work suggest that he might not have visited all the places he depicts as memory. A landscape recreated from a tourist postcard is offered as evidence that he drew from sources other than his inner eye—but if memory is imperfect and needs crass supplements, that only affirms the necessity, and more importantly the possibility, of art. Form exists because content can no more tell the truth about itself than lie. The putative inaccuracy of Yoakum’s recollections gives the exhibition’s title an endearing stubbornness, like a witness insisting on a UFO sighting: I saw what I saw! Indeed, a pink UFO hovers in two drawings, a stand-in for Yoakum’s one experience, wildly strange to him, of traveling by airplane. Things have to be believed to be seen.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Flying Saucer in 1958, n.d. Purple and blue felt-tip pen, pastel, colored pencil, and blue ballpoint pen on paper, 11 7/8 × 9 5/8 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

Yoakum’s use of mundane sources like postcards reintroduces an anchoring note of banality. The young, mostly white Chicago artists who felt they had discovered him treated Yoakum as a miraculous savant. But he did not exist outside necessity. He worked all his life. He fretted that his pension check would be stolen. For many years, his children were strangers to him. Another world, drawn not in ballpoint but in blood and tears, stood at his back as he traced the outlines of his past.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Back Where I Were Born 2/20–1888 AD, 1965. Blue ballpoint pen, watercolor, and varnish on paper, 11 15/16 × 17 15/16 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

His metabolization by the art world in the late 1960s was fraught with predictable difficulties. The admirers who mediated his work acquired it at knockdown prices while advertising him as a brilliant primitive. He had produced thousands of drawings, at his peak in the 1960s completing a drawing a day: once monetized by a pass through the wringer of the market, this quantity of work represented a deep well of value. Works that Yoakum had previously sold to neighborhood children for a quarter apiece became expensive commodities, to be hoarded and argued over. After Yoakum extricated himself from an exploitative contract with Edward Sherbeyn Gallery, friends stepped in to protect his interests. Yoakum’s habit of copyrighting uncolored originals of his work and stamping them with dates is understandably defensive. Less conscious, probably, is the anti-museological gesture of writing titles on the drawings, sometimes in an ornate hand. Several works in the show bear the instruction not for sale. They are probably worth a lot of money.

Joseph E. Yoakum, Monongahelia River Falls near Riverside West Virginia, by 1969, stamped 1964. Blue fountain pen, blue ballpoint pen, colored pencil, and pastel on paper, 11 7/8 × 17 13/16 inches. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

What I Saw is within earshot of the teleological vision of African American history presented by Adam Pendleton’s monumental video installation in the nearby atrium. By contrast, Yoakum’s work evinces an entirely personal relation to the past, free in that it relies on no outside object or influence. For better or worse, this past lays no claim to the present or the future. Like memory, which does not exist, it is in a perpetual struggle to be real to itself.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in New York. She has previously written for Artforum, the New Inquiry, and a number of other publications. Recent exhibitions include Wheel of Fortune at ETH in Zurich and The Meaning of Life at York University Gallery in Toronto. Her novella Tuesday or September or the End was published this year.