Nick Pinkerton

Nick Pinkerton

A retrospective mirrors the filmmaker’s layered approach to

memory and time.

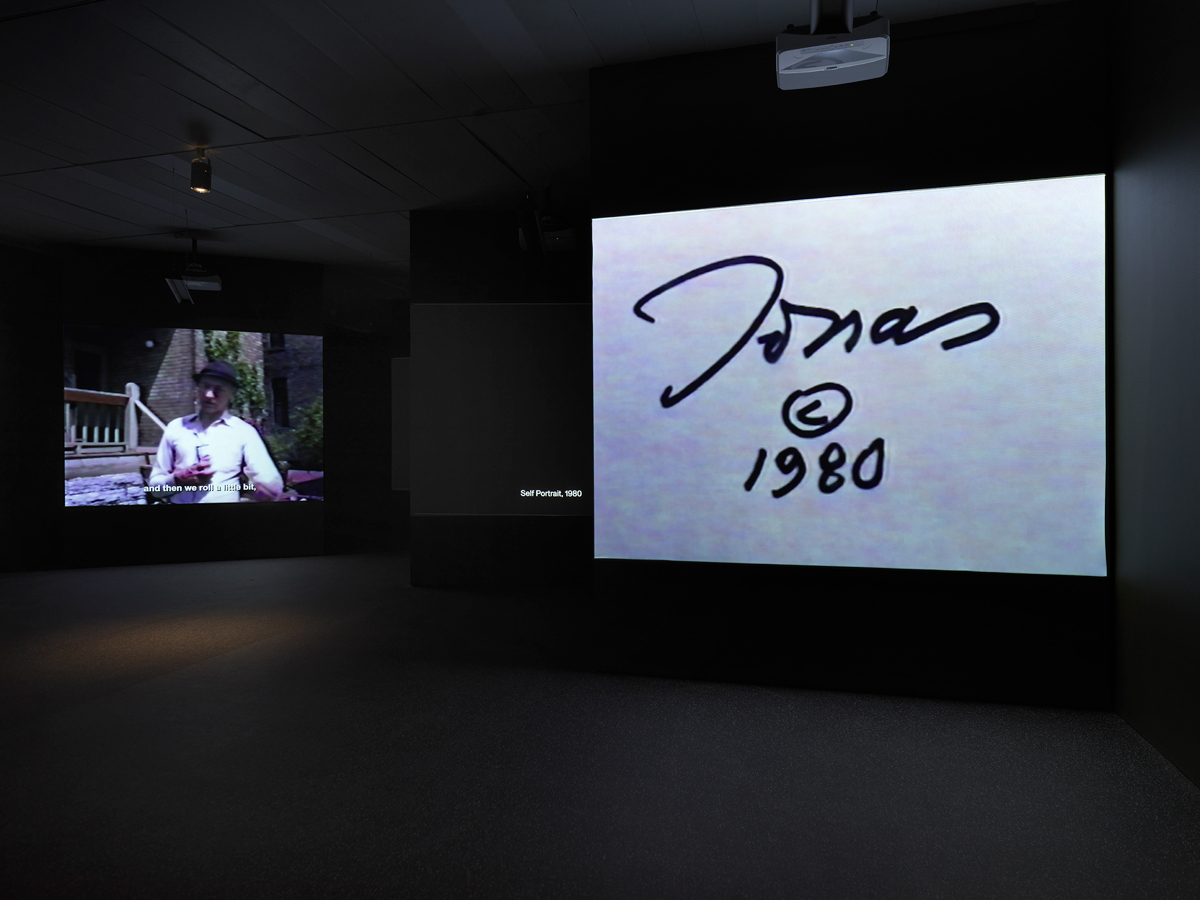

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, curated by Kelly Taxter, with Kristina Parsons, Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through June 5, 2022

• • •

“I have never been able, really, to figure out where my life begins and where it ends,” says Jonas Mekas at the outset of As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000). The lilting voiceover and clipped accent (Mekas was Lithuanian) will be familiar to anyone who knows his work, as will the sentiment, for Mekas’s films are persistent in, among other things, their preoccupation with the persistence of memory and the degree to which the screen of consciousness is a palimpsest on which traces of the past are forever bleeding through into the present.

In his filmmaking as well as in his work as an indefatigable, pugnacious champion of cinema and the founder and director of Anthology Film Archives, Mekas was an ardent archivist, documenting not only his life and those lives his intersected with but also the life of cinema in his time—particularly but not exclusively cinema in the experimental/avant-garde line, his bailiwick as an artist. The raw material of Mekas’s diary films, his best-known and most numerous works, was the footage he shot of his quotidian existence, beginning shortly after Jonas and his younger brother, Adolfas, arrived in New York City in 1949 and ending only with Mekas’s death at age ninety-six, in 2019. This included recurring images of baptisms, weddings, funerals, children, cats, springtime flowers, New York City under a coat of wintertime slush, and bibulous after-dinner conversations—the stuff of the commonplace, though Mekas’s conviction, animating the films, was that nothing was commonplace, that every moment was charged with import and the opportunity for celebration.

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Every archivist is perhaps something of a hoarder, and vice versa, but quite a bit of what Mekas held on to was more valuable than yellowing stacks of the Daily News, by virtue of the fact that he’d had an exceptionally interesting life, from “displaced person” in the mire and muddle of postwar Europe to prime mover and shaker in the midcentury New York art world. Kelly Taxter, curator of Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running at the Jewish Museum, noted that Mekas was able to restore something of the museum’s forgotten institutional history from his own collections, with documents pertaining to the Avantgarde Film Tuesdays he programmed there from 1968 to 1969.

The Camera Was Always Running is a Mekas retrospective in fragments—a further fracturing of a filmography that already offers a view of life as a magpie’s nest of bauble-like moments. It includes eleven of Mekas’s films, from a selection that spans the whole of his career: from his first completed feature, 1962’s Guns of the Trees, to his last, 2019’s Requiem.

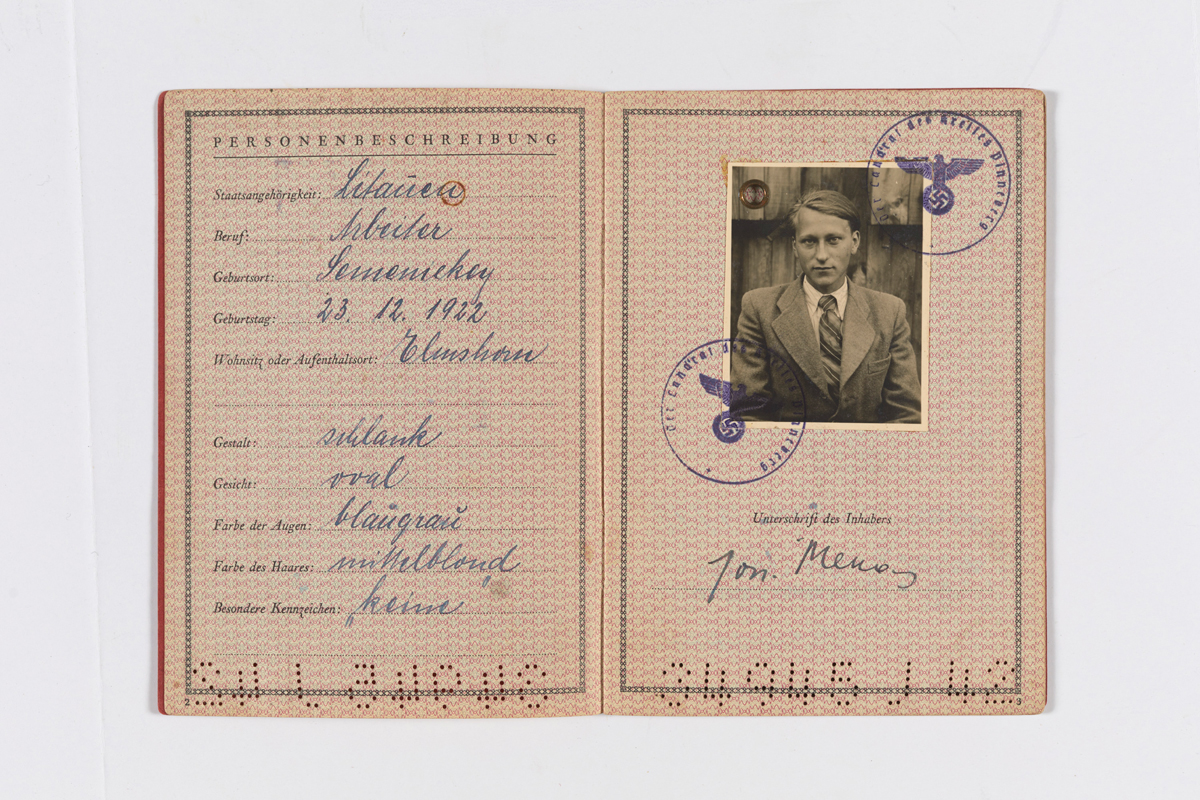

Temporary foreign passport of Jonas Mekas, issued by the German Third Reich. © Estate of Jonas Mekas.

The films can be seen in full here, but only gradually and in segments—or, to use a favorite Mekas term, “glimpses.” After passing a display of artifacts pertaining to Mekas’s early life (the jotting of a poet of barely twenty; the documents of a man without a country), one enters a black-walled gallery space that takes up the greater part of the exhibition’s square footage, equipped with twelve screens. Each film in the program is apportioned out across this span of screens, about ten of which can feasibly be seen at once from the most central seats in the house. From these seats, the accumulated audio from the directional speakers is experienced as cacophony, dialogue comprehensible only via subtitles, though individual sound clarifies as one moves toward any one screen.

The method of partitioning the films is determined, in the main, by the announced reel changes or intertitle chapter headings that were frequent features of Mekas’s works. The twelve chapters of As I Was Moving Ahead use every screen, the six reels of Walden (1969) only six; disparities in length mean each projection begins with a cannonade of images, then fizzles down to a single screen. The films play on loop in “chronological” order, in a program that lasts a little over three hours. Scare quotes seem necessary with that adjective, since Mekas’s films are nothing if not dependable in their problematizing the notion of chronology. (Another line from the As I Was Moving Ahead voice-over: “Memories, memories . . . they come and go . . . in no particular order . . .”)

Jonas Mekas, Walden (Diaries, Notes, and Sketches), 1969 (still). 16mm film, color, black and white, sound, 180 minutes. Courtesy the Estate of Jonas Mekas.

Mekas would have been quite familiar with several experimental films made for two or more projectors—namely 1966’s Chelsea Girls, an underground blockbuster by the subject of one of the films at the Jewish Museum, 1990’s Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol—but his work received the multichannel treatment only later in life, as was done in a 2007 tribute to Mekas at MoMA PS1. Around this same time, new digital projectors were allowing for other existing films to be reconceived as multichannel installations. I recently saw, for instance, two installation works by Chantal Akerman, From the Other Side (2002) and Je tu il elle, l’installation (2007), at Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris, both repurposing previous Akerman films.

In the case of a filmmaker like Akerman, deeply marked by her encounter with structuralist cinema, the attraction of split-screen simultaneity had its own logic, offering a new manner of juxtaposing sections of a work conceived in terms of comparisons and contrasts. Mekas, his chapter breaks aside, was more an artist of spontaneity than structure, and so breaking his films into constituent parts across a dozen screens offers less in the way of intellectual frissons than an overwhelming cascade of images. I can’t say, as in the case of Akerman’s installations, that The Camera Was Always Running left me feeling I had a greater understanding of Mekas’s original works, but I can’t say it left me unmoved, either. If nothing else, at moments it suggests the feeling described by those who’ve had near-death experiences—of seeing one’s whole life flash before one’s eyes.

Jonas Mekas, A Letter from Greenpoint, 2004 (still). Digital video, color, sound, 80 minutes. Courtesy the Estate of Jonas Mekas.

Where Akerman herself executed those installations—one of several such acts of disassembling undertaken since around the turn of the millennium by filmmakers dipping into the gallery world—The Camera Was Always Running, conceived of and gotten underway within Mekas’s lifetime and with his blessing, was designed independently. The curatorial reasoning behind the exhibition’s approach is borrowed from Mekas’s own notes for the premiere of Walden, quoted in entryway wall text: “This film being what it is, i.e. a series of personal notes on events, People (friends) and Nature (seasons)—the Author won’t mind (he is almost encouraging it) if the Viewer will choose to watch only certain parts of the work (film), according to the time available to him, according to his preferences, or any other good reason.”

One of the essays included in the excellent exhibition catalog posits that this permission to wander “intuits a not-so-distant future when filmmakers would screen their works in exhibition spaces rather than cinemas.” But one could just as easily propose it as backward-looking, returning to the casual slipping in and out of cinemas common to early, working-class audiences and beloved by the Surrealists. Mekas was himself inconsistent on the issue of precisely how undivided one’s attention ought to be in the cinema, having, shortly after making this statement, supported the construction of Peter Kubelka’s “Invisible Cinema,” with its peripheral blinders shutting off all distractions from the screen, at the original Anthology theater.

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

To note that The Camera Was Always Running isn’t something that Mekas himself realized isn’t to say that it’s at odds with his legacy—the opposite, in fact. One of the works featured, 1980’s Self Portrait, finds Mekas monologuing to a video camera about the distinction between his current practice of shooting only on film and the potential of video-making, observing: “It makes no difference. These are moving images . . . None of them stands above any other . . .” A fitting tribute, then, to make the man anew, with this scintillating scattering of ashes.

Nick Pinkerton is the author of the book Goodbye, Dragon Inn, available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series. His writing on cinematic esoterica can be found at nickpinkerton.substack.com, among other venues.