Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

“The dark obscured her”: a new volume of poems by Louise Glück.

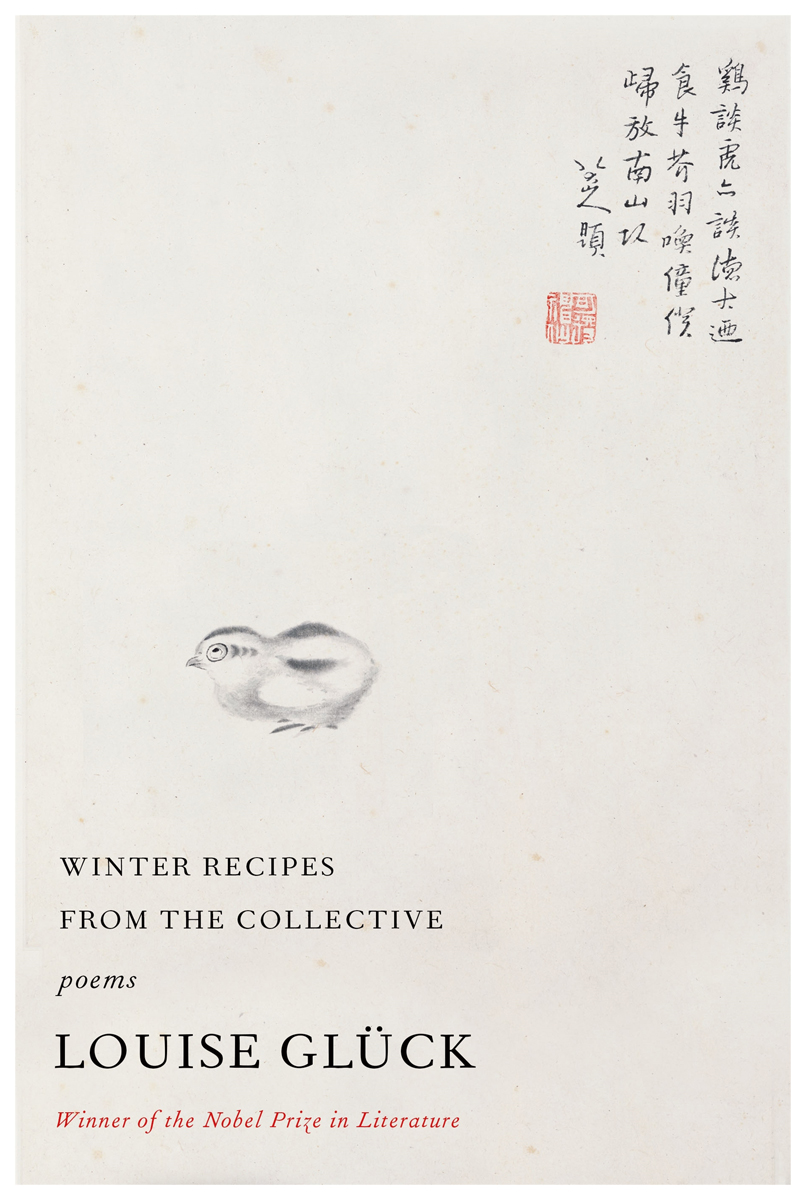

Winter Recipes from the Collective, by Louise Glück,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 42 pages, $25

• • •

Reading Louise Glück through the years has often felt like being friends with someone incapable of small talk. The Nobel Prize–winning poet has been publishing for more than five decades, and much of that time has been spent analyzing despair, melancholy, and anguish—words she’s never had trouble uttering in verse, without irony or apology. Especially in her early books, Glück’s doomful moods can be so unrelenting I’ve sometimes found myself sneering back at the page: Can’t you just get over it already? But the fact that she’s so defiantly unskilled at (and uninterested in) “moving on” is part of what keeps us readers coming back, in hopes of learning how we might live with our own insoluble griefs.

In a time when compulsory happiness has generated a whole industrial complex (a “culture of healing” that the poet describes, in one of her lacerating essays, as “fascistic”), Glück’s recognition of suffering as a constitutive part of life, not a problem to be solved, is a mark of sanity. You’ll find no triumphs in her poems, no half-baked consolations. And yet, severe as a lot of her writing is, there’s tenderness in the way her voice beckons us. Her poems invite us into the grand enterprise of human struggle—a not insignificant gesture, even if it’s the only party in town.

If Glück’s pain principle were merely a dogmatic cudgel to beat us over the head with, it wouldn’t sustain interest for more than a few poems, let alone the thirteen full-length collections she’s published to date. Winter Recipes from the Collective, her first volume in seven years, shows how gifted she is at coaxing new resonances and colors out of a minimalistic vocabulary. The same stark images recur: the wind blows across barren fields; the sun rises and sets in an endless loop. Like any good student of Freud (Glück underwent years of psychoanalysis, starting in her turbulent adolescence), she knows how traumas are both soothed and reanimated by fetishistic repetition. Now in her late career, she’s still crying out the same sad songs, but in a richer, mellower timbre.

These new poems continue down the road Glück has been traveling in the aftermath of 2006’s Averno, an apocalyptically minded masterpiece that pushed her declamatory style to its limit. Since then, she’s seemed wary of revisiting that mode and more invested than ever in the nuances of interpersonal experience. In place of her perpetually devastated “I” is a speaker who’s attuned to the possibilities of friendship and at times even a little contented with her fate.

This openness is evident in “Song,” one of the shortest poems in a book anchored by lengthy, multipart sequences. Glück’s characters tend to be flatly labeled archetypes (mother, father, sister, boy, girl) or mythological figures, so it’s notable that “Song” starts by introducing a person we might assume to be real: “Leo Cruz.” In this act of naming, we sense a newfound generosity. Never one for doling out compliments, the poet goes on to credit this Leo with making “the most beautiful white bowls” and teaching her “the names of the desert grasses.” Where much of Glück’s previous work has been fixated on dissecting power dynamics in relationships—her most conceptually ambitious book, 1992’s The Wild Iris, stages a battle of monologues between God, humankind, and nature—here she’s letting us in on a friendship that’s no less important for being sweet and casual. Her delight isn’t diminished when the tone turns elegiac:

We make plans

to walk the trails together.

When, I ask him,

when? Never again:

that is what we do not say.

He is teaching me

to live in imagination . . .

Typically, Glück renounces idealism and strives to accept things as they are. But in “Song,” she arrives at a contradicting stance: In light of our intolerable reality, isn’t it right that we should retreat into dreams? That’s where, the poem concludes, “the fire is still alive.”

This sign of hope appears at the end of the book, but there’s plenty of heartache that precedes it. Friendship, so life-affirming in “Song,” is a spectral, remote comfort in “Winter Journey,” which follows Glück down the sort of aimless route so common in her poetry:

Every hour or so, my friend turned to wave at me,

or I believed she did, though

the dark obscured her.

The vision of friendship is even more desolate in “The Denial of Death,” whose narrator is abandoned by an intimate travel companion. The rift leaves the speaker stranded in existential limbo at a strange hotel, and because it’s unclear how much time passes in the poem, we don’t know how long it takes for the loss to be metabolized as wisdom. When that wisdom comes, though, it’s an exquisite relief: “You have begun your own journey,” the hotel concierge says, “not into the world, like your friend’s, but into yourself and your memories.”

As in 2009’s A Village Life, Glück’s interest in the social world is channeled into long poems that read like works of short fiction. These stories, unlike the spare, hard-edged ruminations in her early books, are capacious enough to include multiple characters, digressions, and ambiguities. They spiral round and round, never building any consistent momentum or reaching a conventional resolution. Reminiscent of the exitless spaces of Sartre and Buñuel, the hotel in “The Denial of Death” is echoed in the premise of “An Endless Story,” in which an audience is stuck in what seems to be a lecture hall with a woman who has fallen asleep midsentence while telling a fable. The reader has the sensation of gliding through expansive mindscapes while at the same time being physically trapped.

The characters in this book speak in aphorisms and declarations, sometimes as if they’re reciting an ancient script rendered in a stilted modern translation. The absurdist qualities of their speech are thrown into relief by Glück’s incantatory repetition of dialogue tags: “he said,” “I asked,” “she went on.” Throwaway transitional phrases like “This is how it began” and “It happened as follows” create a semblance of linearity that’s upended by the poems’ circling structures.

For all its moments of otherworldliness, Winter Recipes from the Collective addresses and instructs us in the here and now. Maybe Glück would reject the notion that poetry can show us how to live—too utilitarian, she might say, or too sentimental. Nevertheless, the idea is embedded in the title poem, which describes the bare-bones subsistence that an agrarian community cobbles together in punishing weather (if there’s one thing Glück risks over-romanticizing, it’s the rigors of pastoral life). Like the “winter recipes” these people have collected, Glück’s book contains useful information about how to endure the cold.

Robert Frost said the work of poetry is “getting into danger legitimately so that we may be genuinely rescued.” After half a century of sizing up the dangers that disturb the soul, Glück is tending to the redemptive part of the poet’s mission. In doing so, she’s able to draw on the benefits of age: looking back on past periods of darkness, she’s in a position to tell us with some authority that they are survivable (and worth surviving). Glück may despise the platitudes of self-help literature, but it’s clear in this book that she sees poetry as some form of service; in their own way, her words light a path for us. I imagine I’ll be finding solace in this book for the rest of my life.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, the New Yorker, NPR Music, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.