Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

From window peeping to wicked floating: the artist’s Los Angeles survey.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor, curated by Anna Katz with Karlyn Olvido, the Geffen Contemporary at the Museum of Contemporary Art, 152 North Central Avenue, Los Angeles, through

June 6, 2022

• • •

When the New Museum mounted a retrospective of Swiss video artist Pipilotti Rist in late 2016, I dutifully went. The exhibition was thronged with people, and lines stretched around the block. (Its popularity was no doubt bolstered by Beyoncé’s nod to Rist’s widely exhibited 1997 work Ever Is Over All in the pop superstar’s visual album Lemonade, released six months before the show.) But despite the fact that I had grown up with Rist, artistically speaking, I was left oddly unmoved. I suspect it was timing—Trump’s campaign and then election revealed a terrifying rot at the core of American public life. Rist’s color-saturated, trippy videos, with their manipulated musical soundtracks, projected in installations that often invited viewers to stretch out on cushions on the floor or beds or curl up in armchairs—a setup meant to create a feeling of togetherness among strangers— struck me as profoundly out of sync with the urgencies of the moment. We needed real action in the streets, not post-hippie communing. In that context, the work seemed way too Gen X in the worst possible sense of that term: too concerned with the (white, female) body, too inward turning, too focused on a fuzzy notion of the value of “coming together” evacuated of any potential for revolutionary change.

Five years later, some things are different—a new administration and a year and a half of semi-lockdown due to Covid—and some things are depressingly the same: there’s still that rot, and still the need to struggle against injustice. But Rist’s work, as evidenced by a current exhibition, her first West Coast survey—Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor—hits entirely differently now: as not just welcome, but in some ways necessary. Consisting of forty-one videos and installations dating from her first art video, I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much (1986), to a number of pieces from 2021 (some of which are being presented for the first time), the show is marked by a combination of ambition and sincerity that is curiously energizing, even exciting.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Instead of mounting the works in a white-walled, one-box-after-another gallery space (as has often been done, including at the New Museum), Rist has transformed the interior of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s massive Geffen Contemporary to the point that it’s almost unrecognizable. Much of the industrial metal and concrete of the airplane hangar–like structure is hidden behind what are essentially film sets in which individual works have been installed—the exterior façades of a village in one space, the rooms of an apartment in another, a living room filled with oversized furniture in a third.

Pipilotti Rist, Selfless in the Bath of Lava (video still), 1995. Audio video installation. © Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

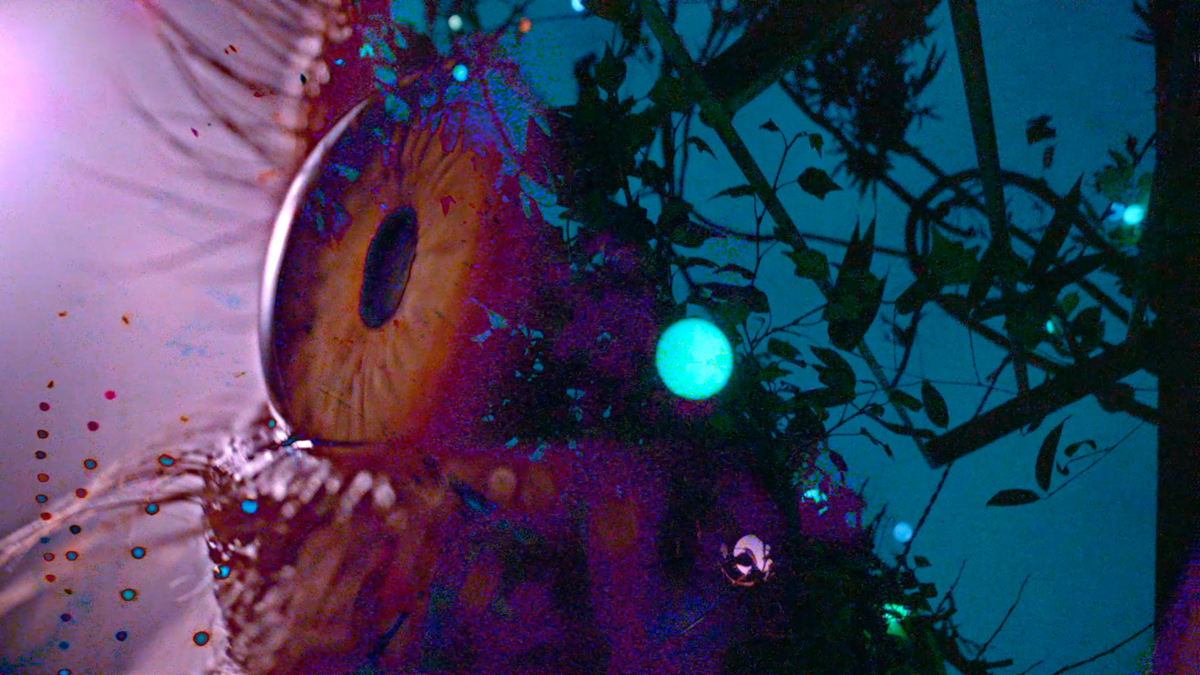

In the first, village-esque area, one video peeks out from a monitor embedded in small hole in the floor (the teensy-weensy and hilarious Selfless in the Bath of Lava of 1995, in which Rist screams ferally out of a fiery void). Others appear in the windows of a house, turning respectable art viewers into voyeuristic creeps (as in Peeping Freedom Pavilion and Peeping Freedom Shutters, both from 2021). Neighbor Understand on the Ground (2021) passes over mounds of landscaping pebbles, while Neighbors without Fences (2021) traverses walls; both dissolve the materiality of their architectural “screens” with an almost psychedelic succession of images that veer between extreme close-ups of bodily surfaces, soil, foliage, and expansive, even panoramic, views of landscape.

Pipilotti Rist, Neighbors without Fences (video still), 2021. Audio video installation. © Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

In the area Rist calls “The Apartment,” one finds a grouping of thirteen works dating from 2006 to 2019. Do Not Abandon Me Again (2015) is projected onto a bed. Caressing Dinner Circle (2017), whose images range from what looks to be a royal banquet to an abstract miasma of colors, is cast onto a dining table nearby. I Burn for You (2018) appears in the opening of a marble fireplace mantle. Prisma (2011) is screened on the surface of a faux veduta painting, so that the light from the video both enhances the whites of the painting and causes the image to dissolve. The fabric that covers the walls is imprinted with a simulated image of the underside of an eyelid (Reversed Eyelid from 2019). The overall effect is intimate and a bit surreal—as if an unconscious has taken up residence here, occupying every nook and cranny, turning this mundane domestic interior into a map of the hidden corners of a mind. After a seemingly endless stretch of working and schooling from home (at least for the more privileged among us), the installation feels like a portrait of our collective stir-craziness.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Sip My Ocean, a 1996 projection that spans a corner of a large room (a favorite device of Rist’s), consists of two mirrored projections that create a kaleidoscopic effect. At a number of points, bodies float through the water along with various objects (a plastic toy camper van, a melamine cup, a cheese grater, etc.), while Rist sings two different versions of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game”—one with all the cheesiness of a karaoke standard, the other in a hilarious screech. Though the video has often been interpreted as a meditation on the pain and pleasure of being in love, a different reading occurred to me as I watched the piece after a summer of environmental disasters, especially when the artist repeatedly sang the lyric “World was on fire and no one could save me but you.” Under the hilarity and almost amniotic pleasure of seeing all this junk floating through the water, it seemed there was a pathos that I’d never noticed before.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Time has been less kind to other pieces. Consider Ever Is Over All, another corner projection. On one side, a woman in a silky blue dress walks joyfully and unmolested down the sidewalk with a metal rod shaped like a flower bud, smashing car windows along the way. The other side consists of an almost infantile, searching view of the rod-flower and other plants. The work is still so brilliant in its use of sound and color, its pacing, and its envisioning of a female utopia in which the destructive energy of the maenad is allowed to roam free. But after all we know about the relationship between white womanhood and law enforcement—think of the Central Park dog walker’s call to the police when she wanted to exact revenge on a Black man who had asked her to leash her pet—the clip in Rist’s video where a female cop walks by the car-smashing woman and flashes an indulgent smile is jarring. It reads now less as a fantasy of an anarchic future than a reiteration of the complicity between carceral feminism and the racist status quo.

Pipilotti Rist, Ever Is Over All (video still), 1997. Audio video installation. © Pipilotti Rist. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine.

That said, there is a kind of generosity to Rist’s exhibition, a welcoming quality that permeates the whole affair down to its smallest details. It extends from the title—Be My Neighbor echoes the sweet invitation Mr. Rogers crooned at the beginning of his children’s show—to Rist’s insistence on referring to museum visitors as “guests,” to the attention to things like the “Do Not Touch” signs that museums use as a matter of course. In the latter case, the artist modifies the usual warning/prohibition by pairing it with an encouragement: “Please do not touch / THINK LOUDER”; “Please do not touch / WALK ON TIPTOE”; “Please do not touch / LET THE CAT OUT OF THE BAG.” Whimsical? Yes. But after seeing our worlds shrink because of a global pandemic with no apparent end in sight, it’s energizing, too: an opportunity to find moments of freedom and release in even the most alienating conditions.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She co-curated the 2021 exhibition Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and is the editor of a forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames and Hudson, 2022). She is also a contributor to the New York Times. She received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing in 2020 and was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.