Tiana Reid

Tiana Reid

The artist makes her US debut in an expansive Brooklyn show.

Grada Kilomba, Heroines, Birds and Monsters series, Sphinx Act I, 2020. C-print, 60 × 40 inches. © Grada Kilomba. Courtesy the artist, the Amant Foundation, and Goodman Gallery.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, curated by Ruth Estévez with Isabella Nimmo, Amant, 932 Grand Street, 315 Maujer Street, and 306 Maujer Street, Brooklyn, through October 31, 2021

• • •

Heroines, Birds and Monsters, interdisciplinary artist Grada Kilomba’s current exhibition, is located in Brooklyn at Amant, a new “art campus,” according to a PR email I received before the gallery’s opening. Heroines is its inaugural show, and also Kilomba’s first in the United States. She was born in Lisbon, studied psychology and psychoanalysis, and has a PhD in philosophy from the Freie Universität in Berlin, where she now lives and works. The exhibition covers the range of Kilomba’s recent practice (photography, theory, performance, film, literature, sculpture, installation, dramaturgy) and its frequent themes (violence, colonialism, history, knowledge production, gender, language). But the complex, winding, and truly impactful show consists of galleries in three different buildings—physical separations that don’t really do the artist’s work justice, diluting its intensity and clarity.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, installation view. Courtesy Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac. Pictured: photos from the Heroines, Birds and Monsters series, 2020.

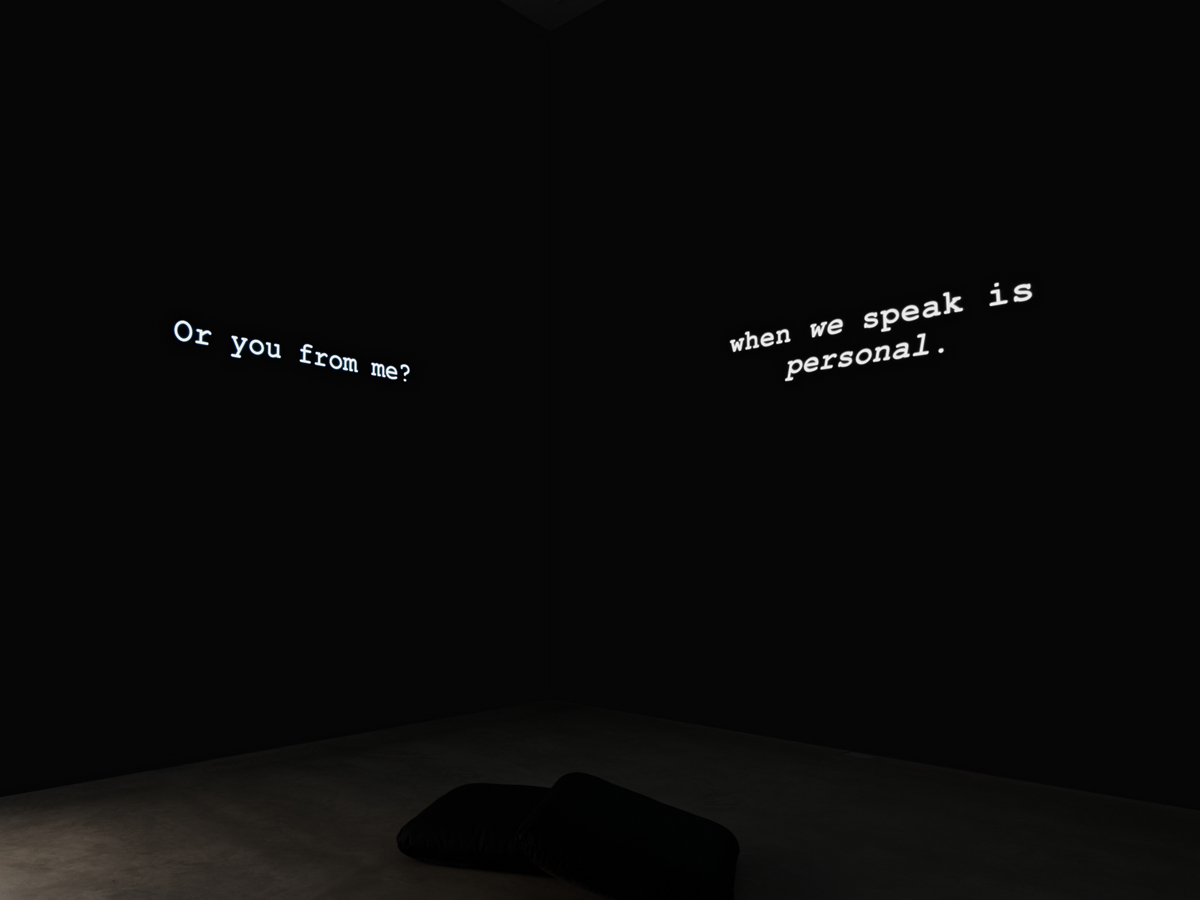

The first building contains installation, sculpture, film, and photographs, including the series after which the exhibition as a whole is named. In a sequence of five large photographs from 2020, the artist, according to the wall text, “captures the Black female protagonists in sculptural poses, mimicking the conflictous world they inhabit, a world between heroines, birds and monsters.” Kilomba and a second woman embody these protagonists, together serving as one Black everywoman. Here she cocoons herself in a bulky black tarp; there she is disappearing; there she is, with wings, on a staircase leading to nowhere. In a room in the back of the first building is The Desire Project (2016), a three-channel text-and-video installation projected on three different walls. It’s impossible to focus on all the words at once (a trio of acts that narrate experiences of alienation in scenes of writing, walking, and speaking). The work is literally cornered in, a feeling augmented by Moses Leo’s tense drumming.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, installation view. Courtesy Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac. Pictured: The Desire Project, 2016.

This kind of visual fragmentation, elaborate obstruction, or psychic interruption—which makes the viewer unable to take everything in—is a hallmark of the exhibition. In the second building, A World of Illusions (2017–19) is composed of screens sculpturally staged in a triangle in the center of the room. This film installation consists of three volumes—Narcissus and Echo (2017), Oedipus (2018), and Antigone (2019)—that adapt Greek mythology, cumulatively intervening in its cultural hegemony. Each volume comprises two channels, one large horizontal screen and one smaller vertical screen to its left (different sound emanates from speakers and headphones). An ensemble of Black actors performs, mimes, dances, and gestures on the larger screens. As if to marginalize the storyteller and the writer, each diminutive screen shows Kilomba reading, alternating between looking down at the script that radically reimagines truth and power and looking devotedly at the players on the larger screen next to her.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, installation view. Courtesy Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac. Pictured: A World of Illusions, 2017–19.

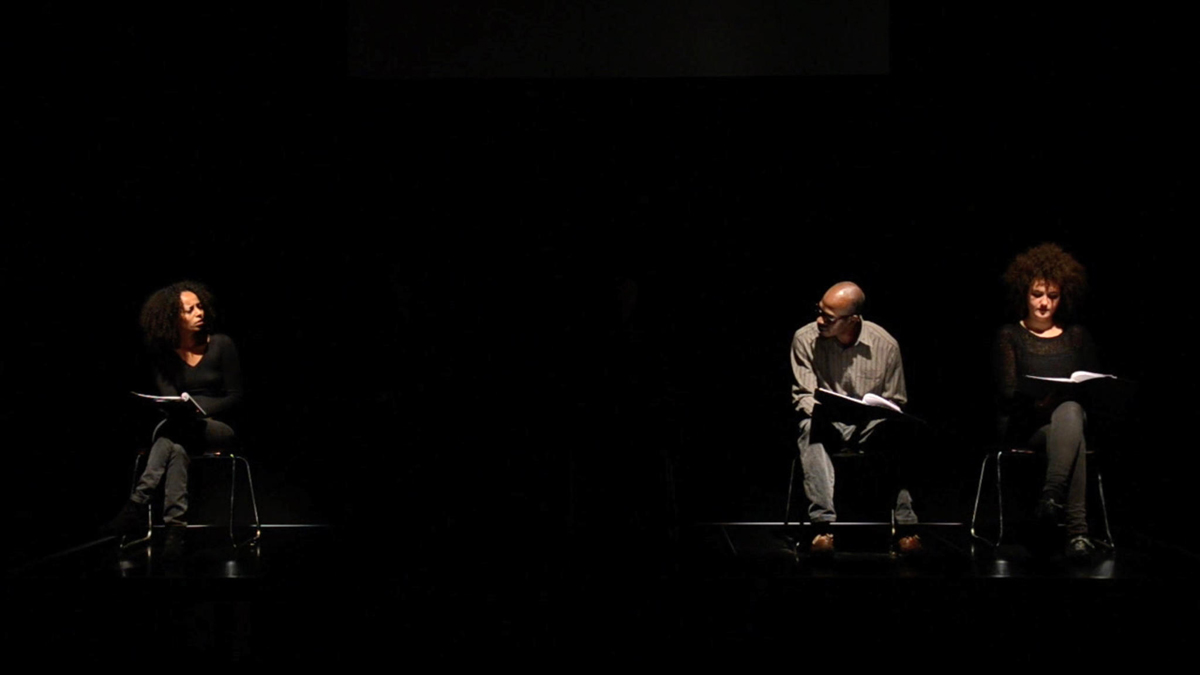

Meanwhile, across the street at Géza, Amant’s “lab” reserved for screenings and performances, is Plantation Memories (2018), a film that stages a reading of Kilomba’s 2008 book by the same name (subtitled Episodes of Everyday Racism). Five spotlit people sit on a black-box stage, wearing dark clothing, each holding a script. In Plantation Memories, what some minimize as “microaggressions” (often there’s nothing micro about them) are placed as part of a larger, terror-filled continuum of trauma. Similarly, a text-based installation in the entrance to Géza, The Chorus (2017), repeats the tropes of banal racisms: “I hate when people touch my hair / Ask me where I am from.” But the exhibition’s strength is that it demonstrates an erudite sway between quotidian forms of violence and histories of colonialism and slavery that linger on.

Grada Kilomba, Plantation Memories (video still), 2018. Video, color, and sound, 60 minutes. © Grada Kilomba. Courtesy the artist, Amant, and Goodman Gallery.

Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism offers some critical theory elaborating on how Kilomba’s work insists that history has not passed. Her writing attempts to address (not redress) certain binding mechanisms of the colonial project: objectification, silencing, hegemony, epistemology. Kilomba quotes from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks in order to describe, in her words, “the painful bodily impact and loss characteristic of a traumatic collapse, for within racism one is surgically removed, violently separated, from whatever identity one might really have.” Here Fanon’s phrase—“I felt knife blades open within me”—comes from Charles Lam Markmann’s translation. The original French verb naître can mean “to open,” but also “to be born.” Richard Philcox’s edition renders it as “sharpening.” Perhaps the entire exhibition spins around this rhetorical tension: To what extent is recognition of one’s Blackness, the birth of an experience, a becoming, however historical, an opening or a sharpening? A surrender or a confrontation? Kilomba’s work is preoccupied not only with the pain of being seen as the supposedly unracialized other sees you amid present histories of violence, but the compatibility between being who you “really” are and who you are perceived to be.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, installation view. Courtesy Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac. Pictured: The Desire Project, 2016.

The image that still haunts me and who I really am is not Kilomba’s own, but one that she, as part of The Desire Project installation, appropriates and places in the middle of a white canvas. It’s an archival drawing of the African woman Escrava Anastácia, a venerated folk-saint figure in Brazil, where she was enslaved. Anastácia’s face, with her piercing eyes, is tiny, floating in the middle of a white expanse—though it’s not her face necessarily that I remember, but the way it is sealed shut, robbing her of speech. “THE MASK,” which appears on a second identical white canvas directly to the right, is an understated word to describe the brutal iron torture device that—by way of a bit clamped between jaw and tongue—fastens her mouth and spiders over her face. Hung around and over the canvas with Anastácia’s face is a long thin necklace with delicate white beads. The work operates like a shrine: to the left are more beaded necklaces—white, light blue, yellow, multicolored—white candles, a glass of water, a bowl of coffee, a pipe, and white lilies on two wooden stools. In the same room is an arresting installation, Table of Goods (2017), which is a sizable pyramidical burial pile of soil patterned with little circles of colonial commodities—chocolate, cocoa, sugar, coffee. Around the perimeter are unlit white candles, further suggesting mourning and grief.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters, installation view. Courtesy Amant. Photo: Shark Senesac. Pictured: Table of Goods, 2017.

Here is what I know: I’m watching documentation of a performance of people reciting a section of Plantation Memories. The testimony, titled “Episode 4,” is about a little girl calling a woman “Negerin” again and again and again. The details are totally banal, totally regular, totally basic, but it recalls a foundational Fanonian scene—“Look, a Negro!”—where one is destabilized in front of the white child anointed by innocence. At first I’m completely alone, sitting on round cushions placed in a line on a platform. But at some point during this time, a nuclear family walks in—two parents and two kids enjoying their Saturday. The older child, about six, who looks white to me, is gesticulating in front of me. The child is pointing, twirling, talking, cackling, screaming. She did not have to call me “Negerin” for me to feel agonized, isolated, parasitic. You cannot make this stuff up, and yet for some reason I could not believe the twisted serendipity of this space-hoarding family, moving about this room freely when a smart work about the plantation logics of the present was playing, now hushed and fading to the background.

Tiana Reid is a writer and scholar from Toronto. She is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Department of English at Brown University. A former editor of the New Inquiry and Pinko, her writing has been published in Art in America, Bookforum, frieze, the Nation, the New York Review of Books, the Paris Review, and elsewhere.