Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A show of the artist’s early photo- and text-based works is all about slipperiness and silence.

Lorna Simpson: 1985–1992, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: James Wang. © Lorna Simpson. Pictured, left: Kid Gloves, 1989.

Lorna Simpson: 1985–1992, Hauser and Wirth, 32 East Sixty-Ninth Street, New York City, through October 22, 2022

• • •

So many Black artists of the 1980s and 1990s—especially women, especially women employing conceptual strategies—are only now receiving their due. But Lorna Simpson has been celebrated from the get-go. Almost from the moment of her debut in 1980, her works were justly acknowledged as key contributions to a larger critique of representation, language, and the photographic sign rooted in social, feminist, and race-based analysis. That recognition was a blessing and a curse, however, as it was for so many of her “multiculti” peers—her art was read by critics as having solely to do with gender and race rather than about ideologies of power writ large. A new exhibition at Hauser and Wirth’s Sixty-Ninth Street space, Lorna Simpson: 1985–1992, focusing on some of Simpson’s most iconic early photo- and text-based work, is ambitious: it takes up three floors and draws from private collections, museums, and the artist’s studio. It also offers a timely reminder of the complexity and expansiveness of Simpson’s thinking.

Lorna Simpson: 1985–1992, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: James Wang. © Lorna Simpson.

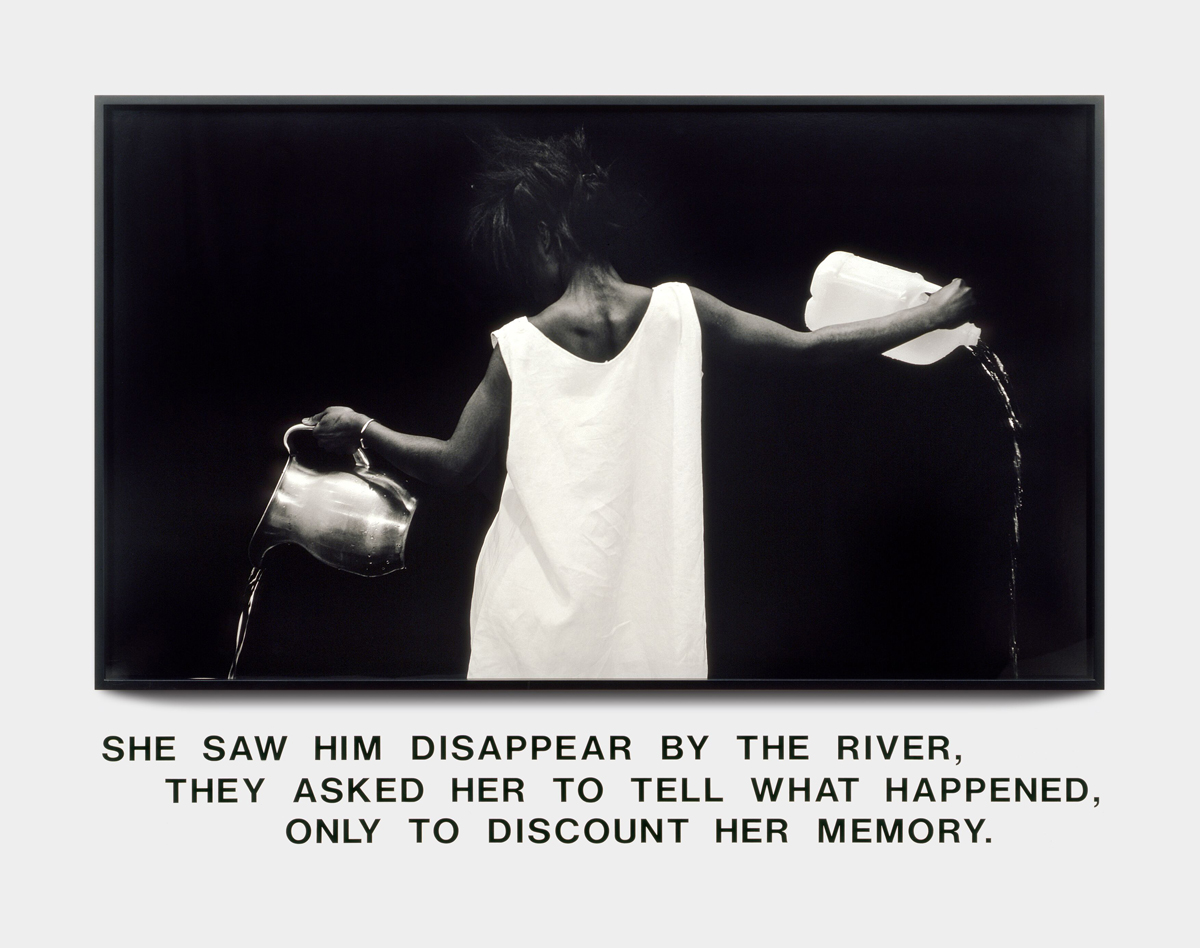

The show opens with Waterbearer (1986), an almost seven-foot-wide framed gelatin silver print hung above a few lines of vinyl wall text. We see a woman from the back, her untamed hair disappearing here and there into the inky background. One hand holds a polished metal jug, this arm held low, and the other holds a plastic one, this arm held higher; silvery streams of water pour from both. Her figure is shrouded by the simplest of white cotton dresses. Below, we read: “She saw him disappear by the river, / They asked her to tell what happened, / Only to discount her memory.”

Lorna Simpson, Waterbearer, 1986. Gelatin silver print, vinyl lettering, 59 × 80 × 2 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Lorna Simpson.

In a 1992 interview, Simpson talked about her interest in writers like James Baldwin, Ntozake Shange, Alice Walker, and Zora Neale Houston: “For them language became a slippery object,” she observed. “I was really amazed at how much they said in silence.” Simpson’s conceptual photography from this era is likewise all slippages and silences. In Waterbearer, the woman’s pose recalls, if obliquely, art historical models—Greek caryatids, comely maids, neoclassical nymphs—at the same time as it acknowledges the burden of real-life labor (look at the way the model’s back and neck muscles flex). How to understand this figure? She is a woman; she is a Black woman; she is perhaps an enslaved Black woman—she is, that is to say, overdetermined within our culture’s scopic regime. She uses an old-fashioned silver vessel, as did so many who labored against their will in plantation houses or, with only slightly more agency, as paid domestic servants in the houses of the rich; or, perhaps, she is not a laborer at all but is simply going about the business of living in her own, well-appointed house. She empties a plastic jug, as so many of us do every day without heed for the environment; or as those living in Flint, Michigan, and now Jackson, Mississippi, are forced to do because of what we might call infrastructural and environmental racism.

What exactly in this image leads me in these directions? What stops me from wandering? My search for meaning is both propelled and held in check by Simpson’s canny ambiguity.

The text is just as hard to pin down, and yet the drama at the center of it—a woman being asked to testify about her memory and having her memory discounted—feels like it could be the narrative of so many women who have tried to report sexual harassment or rape. But what if he wasn’t her rapist but her lover? What if they didn’t want to protect her but to punish him? Image and word function as a Rorschach test, drawing on real histories and experiences (above all those of Black womanhood), but forcing viewers, at the same time, to understand narrative—this narrative, maybe all narrative—as a set of projections.

Lorna Simpson, Untitled, 1988. Four black-and-white dye-diffused Polaroid prints, 29 1/4 × 103 × 1 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: James Wang. © Lorna Simpson.

In this period, Simpson’s women are usually seen from behind, protected from the viewer’s gaze; when they are seen from the front, they are cropped so their faces are not visible. In both cases, the artist bars the uses to which other such clinical compositions have been put in the past: anthropological typologies of the races, criminological arrays of deviance, and so on. The reference to, and undoing of, notions of classification runs deep: in Untitled (1988), a series of four framed Polaroids (without any textual component) comprises near-identical—but crucially different—shots of a woman from the back; in She (1992), a figure in an oversize black suit sits on a chair, subtly shifting position over the course of four frames, at once confirming and contradicting the word “female” engraved on a plastic plaque above the photographs; in Kid Gloves (1989), a five-paneled piece, a woman in a white dress and white gloves is juxtaposed with text that suggests an almost scientific analysis of mores—“Social Isolation,” “Social Grace,” “Social Order,” “Social Code,” and “Social Agreement.” In all of these cases, any promise of categorical order is a myth, a fantasy that the works constantly frustrate.

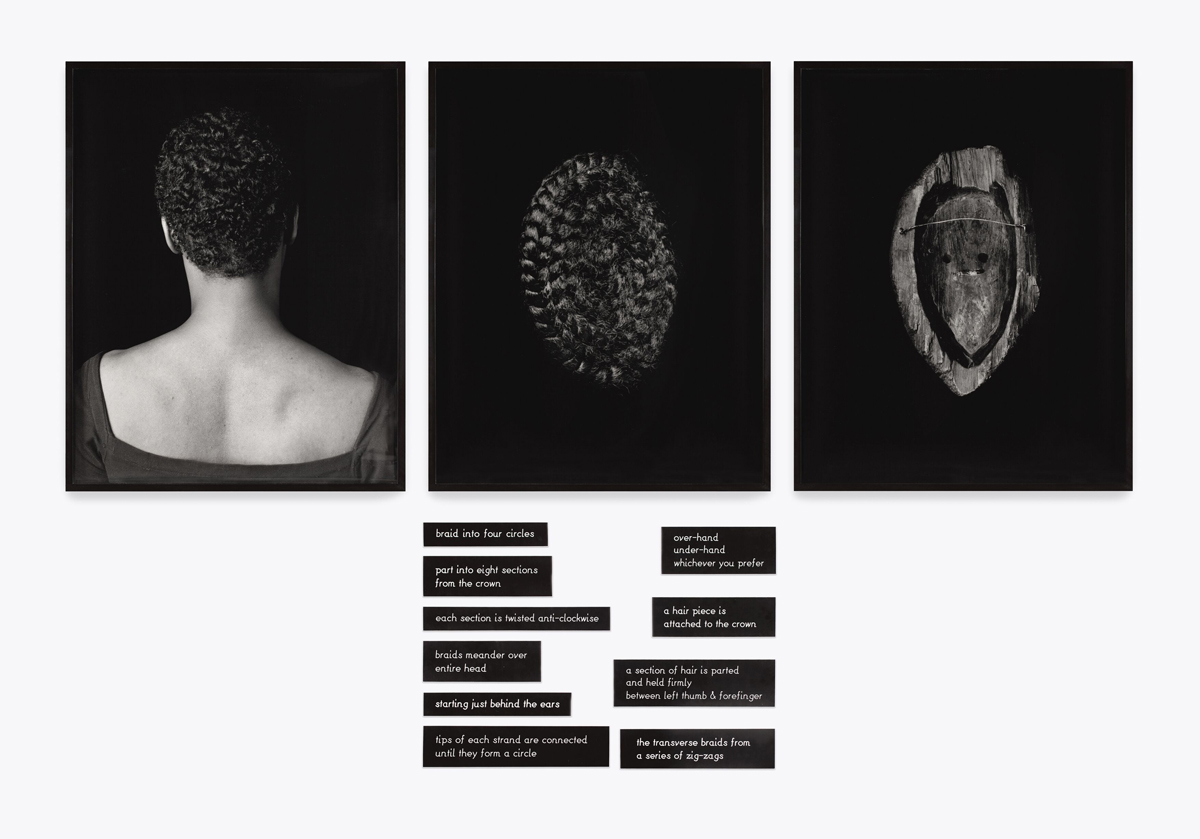

Lorna Simpson, Coiffure, 1991. Three gelatin silver prints, ten engraved plastic plaques, 72 1/2 × 106 × 1 7/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Lorna Simpson.

In a number of pieces from 1991—those which feature African masks—the view from behind hits a bit differently: not so much as a refusal of the beholder’s gaze as an invitation to look with other eyes, to look not at someone but with someone. Flipside, Personal Effects, and Vantage Point are each composed of two gelatin silver prints with accompanying text, juxtaposing the back of a woman’s head paired with a wooden mask. In Coiffure, instead of a bipartite composition we see a third photograph, this one of coiled braids; while in Queensize, two photo panels sit on top of one another, so that the mask hovers above a near life-size image of a woman cut off at the shoulders, her hands grasping her left hip. Pointedly, as with the human figures, we are offered only the back of the masks, not the front. To witness these objects from the perspective of someone wearing them forces viewers into a relationship of identity rather than difference, at least partially and momentarily. For women of African ancestry, there might be another layer of empowerment: in almost all African cultures that use masks for ritual purposes, only men are permitted to wear them.

Lorna Simpson, Queensize, 1991. Two gelatin silver prints, one engraved plastic plaque, 102 1/4 × 49 1/4 × 1 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: James Wang / Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. © Lorna Simpson.

Here, we get a glimpse of how Simpson’s opacity opens up a space for dreaming—an opportunity to explore the exigencies of a symbolic regime that defines us and even traps us in a set of terms not of our own making. Simpson’s work is about Blackness, and Black femininity, to be sure, but it’s also a reminder of the slipperiness of meaning, of how power comes into being and can, at least provisionally, come undone.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She is the editor of the newly released book on Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames & Hudson, 2022). She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.