Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Ling Ma’s stories evoke surreal situations to capture the paradoxes of

lived experience.

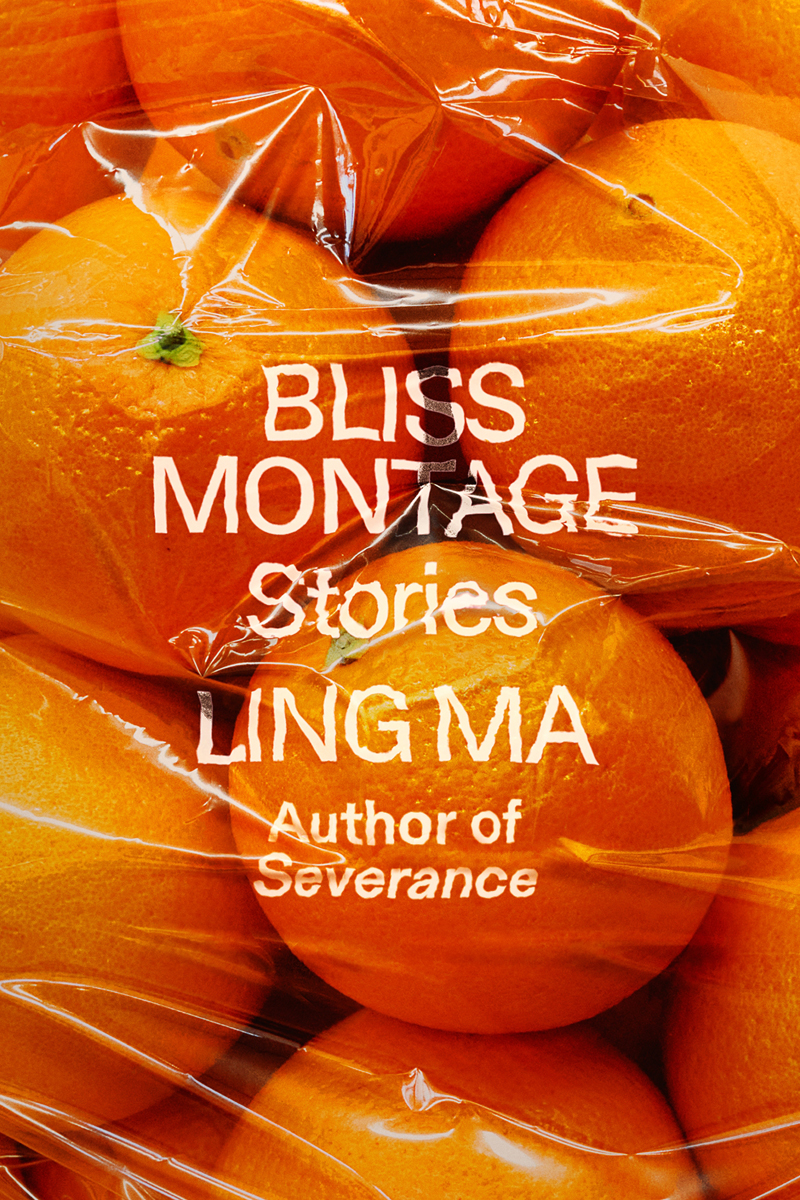

Bliss Montage, by Ling Ma, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 228 pages, $26

• • •

Fiction is where the surreal finds harbor, praise the Lord, and where the simultaneity of experience can be honored in full. Immaterial fears grip our consciousness as tightly as mothers and the weather, a contradiction more suited to the magic and mundanity of fiction than, say, vox pops on Oxford Street. Your hundred ex-boyfriends really do live in your LA mansion while also not being there at all. Your mother can be both your mother and a character in a published story that you talked about in an imagined story in which you discuss your real mother talking about your published stories.

Those are both examples from Ling Ma’s new collection, Bliss Montage. In 2019, she told PEN America that she had once wanted to be a journalist, and this tendency toward reporting is reflected in her non-player characters: fungal spores, the supply chain, white MFA students who gatekeep Chineseness for Chinese American writers. For a reported story on any of these, Ma would have been encouraged to reach one single conclusion about mycelium or MFA bros. Fiction, on the other hand, can make a gang of discontinuous events simultaneously plausible, allowing stories to approach and then surpass reporting’s capacity for facticity. Language, ever insufficient, can only embody thin slices of perception, so we need the simultaneity of stories, no matter how many times the ghosts and mothers double.

The stories in Bliss Montage bracket the release of Ma’s well-regarded 2018 debut Severance, a meditation on bullshit jobs (right on time), a pandemic (well before COVID-19), and zombies (on the later end of the zombie bubble) that unfolds more like three novellas than one novel. The two oldest pieces in Bliss Montage are “Yeti Lovemaking” (featuring a yeti-human hybrid), published by Unstuck in 2012, and “Los Angeles” (the one with all the boyfriends), published by Granta in 2015. The remaining stories were written during the pandemic, and the newest, “Peking Duck,” was published by the New Yorker in July.

In that one, a set of nesting spoons, the narrator moves from China to America as a child and grows up to become a writer who keeps encountering a borrowed memory about Peking duck, a memory which appears in stories by both Mark Salzman and Lydia Davis. Can someone else’s memory become yours? Can your cover version of a memory become the definitive version? As a child, learning English from books and TV, the narrator opts for simultaneity as practice and philosophy: “I tell the truth in Chinese, I make up stories in English. I don’t take it that seriously.” When she later ends up reading her work aloud in an MFA class, another student accuses her of trucking in stereotypes and “Asian minstrelsy.” Ma’s only comment on the gatekeeping is the italics, and then the MFA story muscles in and takes over “Peking Duck.”

In it, the narrator’s mother, while working as a nanny, is terrorized by a salesman who barges into the house only to be scared off by the return of her charge’s parents. A tone-deaf creep, the employing mother tells the narrator’s mother to clean up the food her assailant had dropped. “ ‘Someone has to clean up. And I didn’t make this mess,’ she says, not looking at me.” The mother quits. Ma slots both a mansplainer and a Karen into her story without distracting from the relationship between a daughter and a mother who is grappling with life inside her daughter’s simultaneity: “There are so many mothers in your stories, what am I supposed to think?”

Though I liked the dissection of New York’s precarity and the Shenzhen production scenes in Severance, I can’t hang with zombies. (There is something fascist about shooting your buddy just because she becomes a zombie. No solidarity!) In Bliss Montage, the unreal is more real. The husband in “Los Angeles” who speaks by saying only “$$$$$$$” is a vision I am familiar with. “G” is about a drug of the same name that grants you an “invisibility cocoon,” which is both the high itself and the fulcrum of a power play between two childhood friends. Ma’s imaginary drug treats anxiety with almost imaginable enhancements:

It lifts the tiny anvil of self-consciousness. You can go anywhere, unimpeded by the microaggressions of strangers, the obligatory, waterlogged civilities of friends and acquaintances. Just go out and voyeur around, nothing but a Guston eyeball bouncing down Amsterdam, where patrons dine alfresco on a Thursday night, celebrating, already, the impending weekend.

The friends meet in the cross-firing dreams of two mothers, whose needs are satisfied by their children’s achievements and thwarted by developments like the “awkward Goth phase” (a struggle not limited to Chinese Americans). After falling out, the friends reunite as adults to take G before our narrator makes a “French exit” from New York. Bonnie, though, has another idea, and measures her dose of G such that she rematerializes but our narrator does not. Bonnie has metabolized her mother’s ambition and created a variation on the post-college career shootout, where the successful leave the less employed to their own invisibility. The class struggle here is as real as G is not.

Freed of zombies and the monochrome of shock, Ma has more time with these stories for the force of sentiment. The baby arm hanging out of its mother’s vagina in “Tomorrow” is not a cue for body horror. “She gave it a little massage. Every week, she trimmed its nails.” That kind of unchecked feeling is combined with simultaneity in “Office Hours.” A film student grows up and takes her former professor’s job in media studies. When the story begins, she is spending hours with the professor, “languishing in the amnion of his office.” She smokes there, too, enough that, “by the time she graduated, she was a chain-smoker.” When the office becomes hers much later, and her professor is terminally ill, they return to it together one last time. He takes her on a small tour of the closet: behind an armoire, there is a passage into a landscape beyond time. While letting herself see this parallel world without resistance, the narrator resists taking off her coat, because it would indicate an agreement “to accept the plausibility of her surroundings.” In the moment, we sometimes resist a simultaneity that fiction can later slow down and rearrange, and confirm, for us.

After the teacher’s death, the student returns to the office, now hers. Simultaneity acts in both the form of the story (which isolates her college years and her adult working life and tapes them into a fizzing pair) and the events themselves (a person who meets another magical person, who can quote Mary Ann Doane and Laura Mulvey). Our narrator, as she lives through Ma, has become the one fielding students and making cocktail talk with underminers, the professor with a secret landscape in her office, the only person sifting these dreams and fears and this particular march of days, all of it only occasionally brightened by a closet. Even a memoir might lapse into explanation, that ruining voice. Ling Ma knows that her silence is what lets her events float in their own logic, eventually stacking up in the space she affords them, cleverly bumped into that one last unified moment of being read.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.