Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Cuban writer Marcial Gala receives his English-language debut.

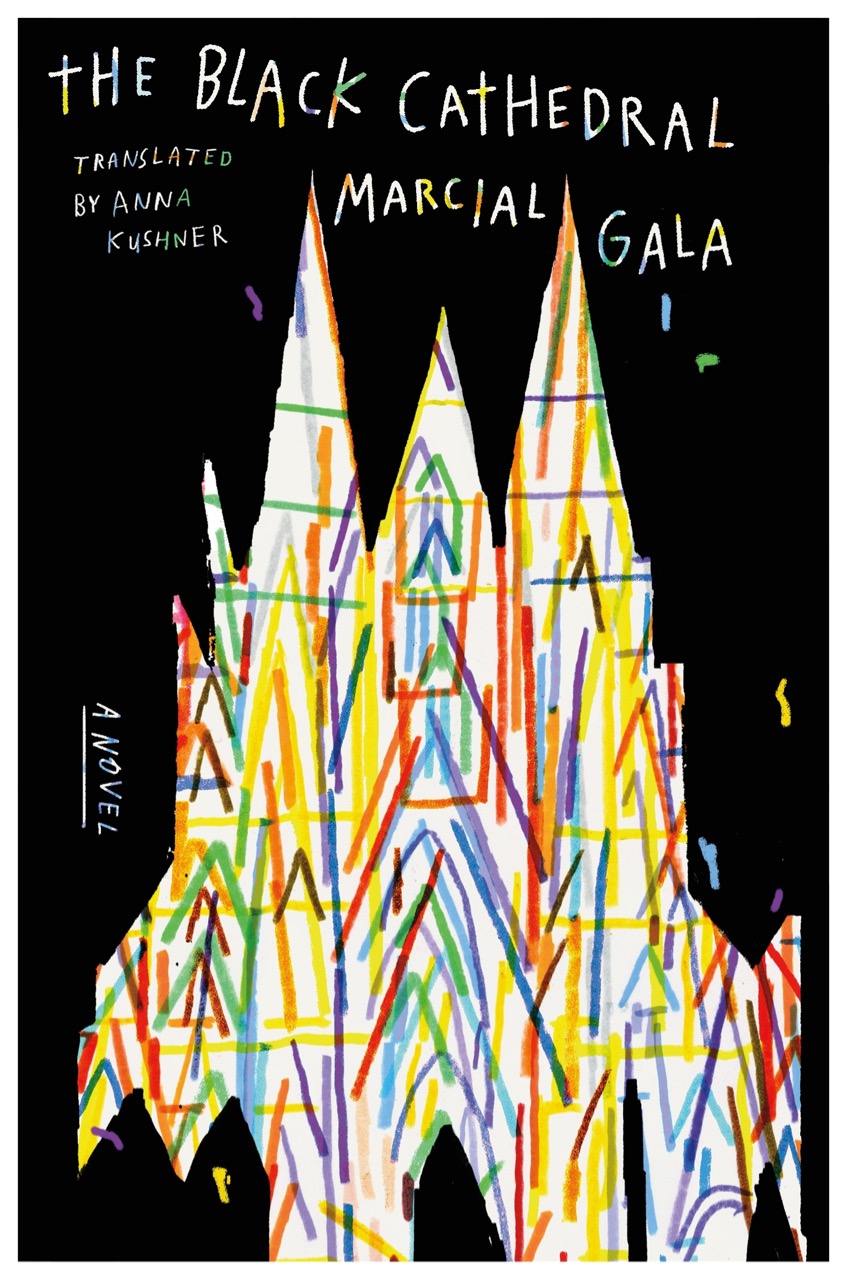

The Black Cathedral, by Marcial Gala, translated by Anna Kushner,

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 209 pages, $26

• • •

The Black Cathedral was first published in 2012: it’s the third of Marcial Gala’s five novels to date, and the first to be translated into English. The award-winning Cuban writer lives part of the time in Cienfuegos, the coastal city where this book is set. In Gala’s many-voiced tale, Cienfuegos is a provincial capital harboring mundane material aspirations, ingrained racial divisions, and serious artistic longings in competition with religious urges. It is also a place of extreme violence. The cathedral of the title remains an unfinished edifice planned by one Arturo Stuart, a zealous and despotic black preacher who arrives in town with his family, to general amazement. “Too much furniture for someone moving into a neighborhood like this,” remarks the novel’s first narrator, Maribel García Medina. “This can’t be good,” says the second, known as Guts. The Stuart sons, David King and Samuel Prince, appear enigmatic to the locals: Is the first “a total nutjob,” and the second “a fairy”? The daughter, Johannes, is already an artist, and later she will provide a neat précis of Gala’s seamlessly fragmented narrative style.

The Black Cathedral proceeds in a series of short, laconically voiced glimpses of the cathedral and its mysterious makers. The Stuarts are usually offstage, the action being reported by a succession of neighbors, teachers, would-be lovers of the Stuart children, vicious hoodlums, and a haplessly utopian architect who quotes Adolf Loos (“ornament is crime”) and imagines that the achieved Church of the Holy Sacrament of the Resurrected Christ will be a serene, austere modernist structure, pointing the way to the city’s, and maybe all of Cuba’s, future. (The novel’s epigraph is from the poet José Lezama Lima: “Cuba has its cathedrals in the future.”) But the grand project is mired in messy reality, and nobody is quite sure what the building is meant to signify, or why it has acquired its name. Is it a cathedral for the city’s black population, or a dark metaphoric expression of some lurking evil? Everybody hints at the Stuart boys’ part in some atrocity or disaster, but nobody will yet name it.

Meanwhile, other horrors are being perpetrated. A black con man, Ricardo Mora Gutiérrez, known as Gringo, introduces himself thus: “I had killed my first guy. I slashed his neck and didn’t stop until his eyes were like a dead cow’s. ‘Who has the biggest cock now?’ I asked him, then I cleaned the switchblade with the sleeveless shirt he had been wearing to show off.” With his sidekick Pork Chop, Gringo embarks on a murderous spree, luring visitors to the city with promises of good deals on motorbikes or air conditioners, then cutting their throats and selling their flesh as choice meat to unsuspecting citizens. If there is a narrative core to The Black Cathedral, it belongs to Gringo, for better and worse. With his flip, callous recall of his crimes, he is by far the most vivid character; he is also the reason much of the novel reads as a catalog of physical brutality and rampant misogyny. It’s only when he moves to the US and starts marrying and murdering older, richer, white women that Gringo meets his comeuppance.

While Gringo languishes on death row, a chorus of other characters sends the novel in disparate directions. There is Juan Pablo Sosa Romero, a painter and engraver who briefly dates the talented Johannes—she will ultimately flee Cienfuegos to become a famous artist and marry a footballer in Spain. There is Berta, who is haunted by the ghost of Gringo’s first victim: “I knew he was dead because his eyes were rolled back and he was naked.” The ghost visits Gringo too, wishing to know why he was cut short in his prime. There are the constant references, from believers in the Stuarts’ project and its skeptics, to some catastrophe to come. In other words, Gala’s novel travels about in time and space a little in the way the ghost does, dispersing anecdotes, regrets, and fragile hopes, never exactly settling into an agreed story. Throughout, the supposedly minor characters are more lucidly drawn than the family at the novel’s heart.

As for the cathedral, at first glance it is hard to think of a more brooding or obvious metaphor for a city’s, or a culture’s, ambitions and desires and efforts at self-representation. But the thing itself is scarcely there—it’s a phantom on the page, every bit as mysterious as its pious inventor. At times, it feels as though the novel is missing its symbolic center, as if even a little more exposition, a more exact expression of his vision by Arturo Stuart, might unify the vagrant whole.

Except: The Black Cathedral is finally not about larger ideas of redemption and the future at all, but about predictable paths of minor failure and major self-justification. It’s no accident that key events—Gringo’s killing spree in the US, for instance—happen during the early years of the Obama administration: there’s a pervasive sense of dashed hopes, business as usual, faith ignored or betrayed. That the disappointment in a black president is most persuasively expressed by a black murderer—this is just one of the novel’s more devious turns. Surprisingly, the only thing Gala’s characters seem to have unalloyed trust in is writing itself. Or rather, poetry in particular. There is hardly a voice here that doesn’t at some point tell how literature became a guiding principle or practice, a consolation or a route out of Cienfuegos and its religiosity, its violence, its hatred of women. Rimbaud, Villon, Ulrich von Hutten: the names circulate like so many romantic promises of escape in the face of Arturo Stuart’s mad authority. In the end, it’s his daughter who declares an artistic counter to his monomaniac project, which sounds much like Gala’s collage method: building up her painterly vision out of high-definition “layers of reality.”

Brian Dillon’s essay collection In Pieces will be published in May by Sternberg Press.