Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

The latest novel by Helle Helle captures with casual intensity and uncanny grace the relationship between a terminally ill mother

and her teenage daughter.

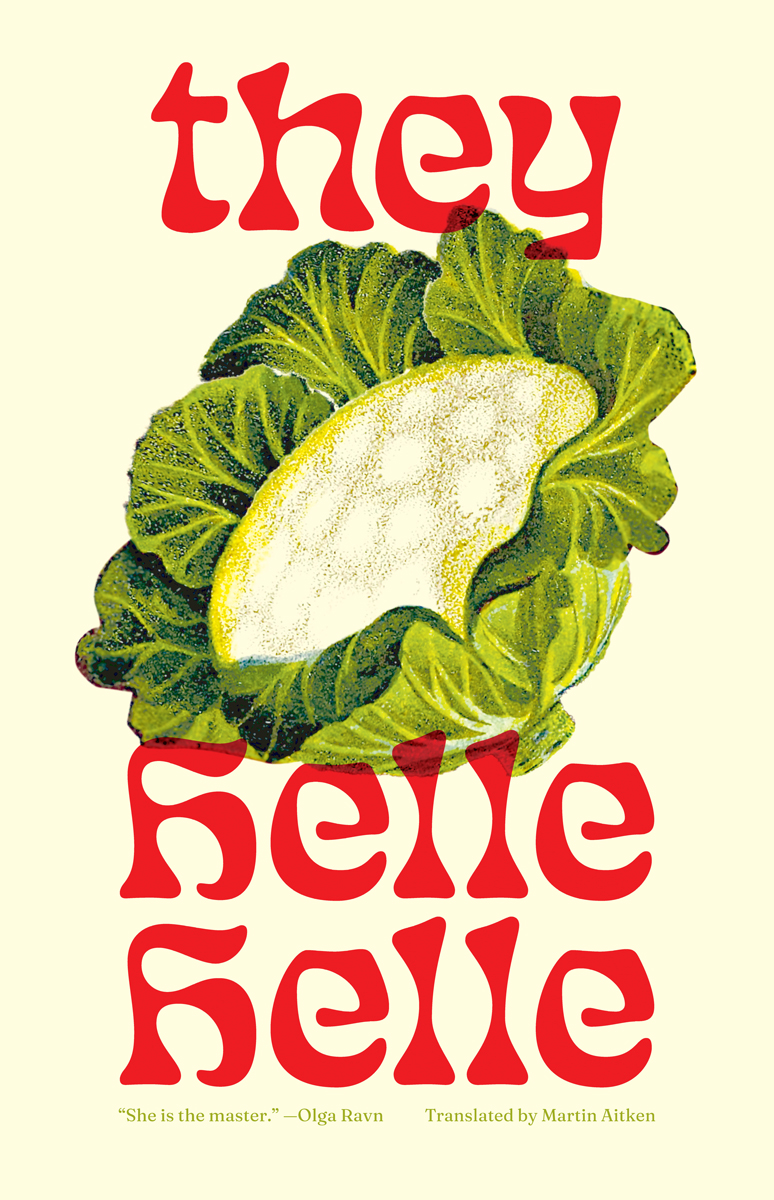

they, by Helle Helle, translated by Martin Aitken,

New Directions, 151 pages, $15.95

• • •

For the teenage child of a dying parent, the knowing and not knowing occupy together a mind at once anxious and oblivious. There are hints and insinuations, disasters on the way to larger disaster, revelations you would like to run away from, but if you are lucky you inhabit, for a while, a muted universe of consolation and distraction. In her new novel, they, translated by Martin Aitken, the Danish writer Helle Helle captures with uncanny grace the relationship between an unnamed mother and her sixteen-year-old daughter following the former’s cancer diagnosis. The disease too is unnamed, and the mother’s terminal outlook never exactly confirmed—but both are clear to the reader. If she dies, warns the mother one night as they make dinner, her daughter must not use the “contemptible” local undertaker who gives away free wine. “It’s a good thing you’re not going to die, then,” says the girl, and turns back to the frying pan. Life carries on: they is a book overwhelmingly devoted to mundane detail, but all of it is fraught with feeling.

Helle’s capacity to make compelling fiction out of the most ordinary objects and events is partly a matter of tense. The novel not only unfolds—persists would be a better word—in a constant present, but all retrospect happens in the same timescale: “She doesn’t wash her hair during her long shower earlier on, so she does it now.” Or, more confusing: “It’s her mother and Marna and the handyman who refurbish the shop seven years ago.” This narrative habit sometimes sounds awkward—places they have lived before seem part of the same present—but it keeps characters and reader inside the close orbit of home, school, hospital, teenage outings, and parties. Mother and daughter live together above a hairdresser’s shop in Rødby, a small town on the southern Danish island of Lolland. Their apartment has been painted to match a dusty pink candlestick they never use. Much of the time they sit by the window and watch people pass, or they read the weekly local paper. There are school supplies to think about, bus and train schedules, layered hairstyles—or not. It is some time in the 1980s.

Before and after the mother’s diagnosis—“I must have swallowed a stone,” she says on discovering a lump under her breast—she and her daughter eat, and think about eating. It is rare to read a novel in which food, its purchase and preparation and consumption, is described so often or with such precision. Everybody is always offering everybody else pieces of fruit, some cheese, or a treat to go with their coffee. In the back room of the shop where her mother works, “the conversation revolves around savory pancakes.” Tomorrow’s breakfast is a recurring preoccupation. The non-Scandinavian reader learns a fair amount about crispbread sandwiches and øllebrød, a bread-and-beer porridge. There is of course the mother’s diminishing appetite, and the daughter’s voracious adolescent one, but all this food is primarily a matter of time and timing: the days and hours marked by what there is to eat and what to say about it. So that when her mother is hospitalized, the girl starts up her own rhythm of domestic life. Her clothes are strewn everywhere, but her experiments in the kitchen are meticulous: she uses up what food she finds at home and spends none of the money her mother has left her for household expenses.

Such attention to the rituals of family life is one way for Helle to depict the self-involved presentism of adolescence, which becomes laden with pathos the moment the daughter tries to keep it all going on her own. Outside of life with her mother, the nameless girl does normal teenage things, which Helle describes with casual intensity. She is quite brilliant on the sheer stoicism of teenage experience, the long hours waiting for something to happen, the way one is at the mercy of logistics (a broken bicycle, the wrong bus ticket) and absence of money, the endless anxiety about whether anyone is looking at you, which overwhelms any childish or adult ability to look, say, at the light or water in a fjord. The sixteen-year-old drifts about with girls from school, attends a sedate-sounding party, gets left behind on the way to a concert, and occasionally gets naked (but little else, it seems) with a boy she is not very interested in. She also, in one of the novel’s more ambiguous aspects, spends time with a male schoolteacher, clings to him on the back of his moped, shares some uncertain interludes before he rushes away. Again, Helle is masterful at giving us a laconic description of something that might well be darker.

In its minimal fashion, they is a kind of Künstlerroman in which the tireless delineation of minor incidents, the enumeration of meals and snacks, the concentration on gestures and sensations, and the sensibility that voices all of this really belongs to the daughter, who will one day be able to tell it in a frozen but expansive present tense. She is already a writer of sorts, careful to scribble down recipes found or invented, and keen to start speaking in longer sentences. (Nothing says sixteen like telling yourself this is how I should start speaking.) And she has a book in mind: “She envisages the novel Sidewalk Thoughts as a brick of a book based on the observations she’s made on her way to and from school over the years. It’s been a work in progress ever since fourth grade, though as yet she’s written nothing down.” She gets a pen and pad out at home, but does not know how or where to start. One answer might be: start right in the midst of the most banal parts of your extravagant and perilous existence. The opening sentence of they is: “Later she goes over the fields with a cauliflower.” And a world of loss and lyricism follows.

Brian Dillon’s memoir Ambivalence is published later this year by Fitzcarraldo Editions and New York Review Books. He is working on Charisma, a novel.