Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

Farewell to outrage: a story collection from John Edgar Wideman.

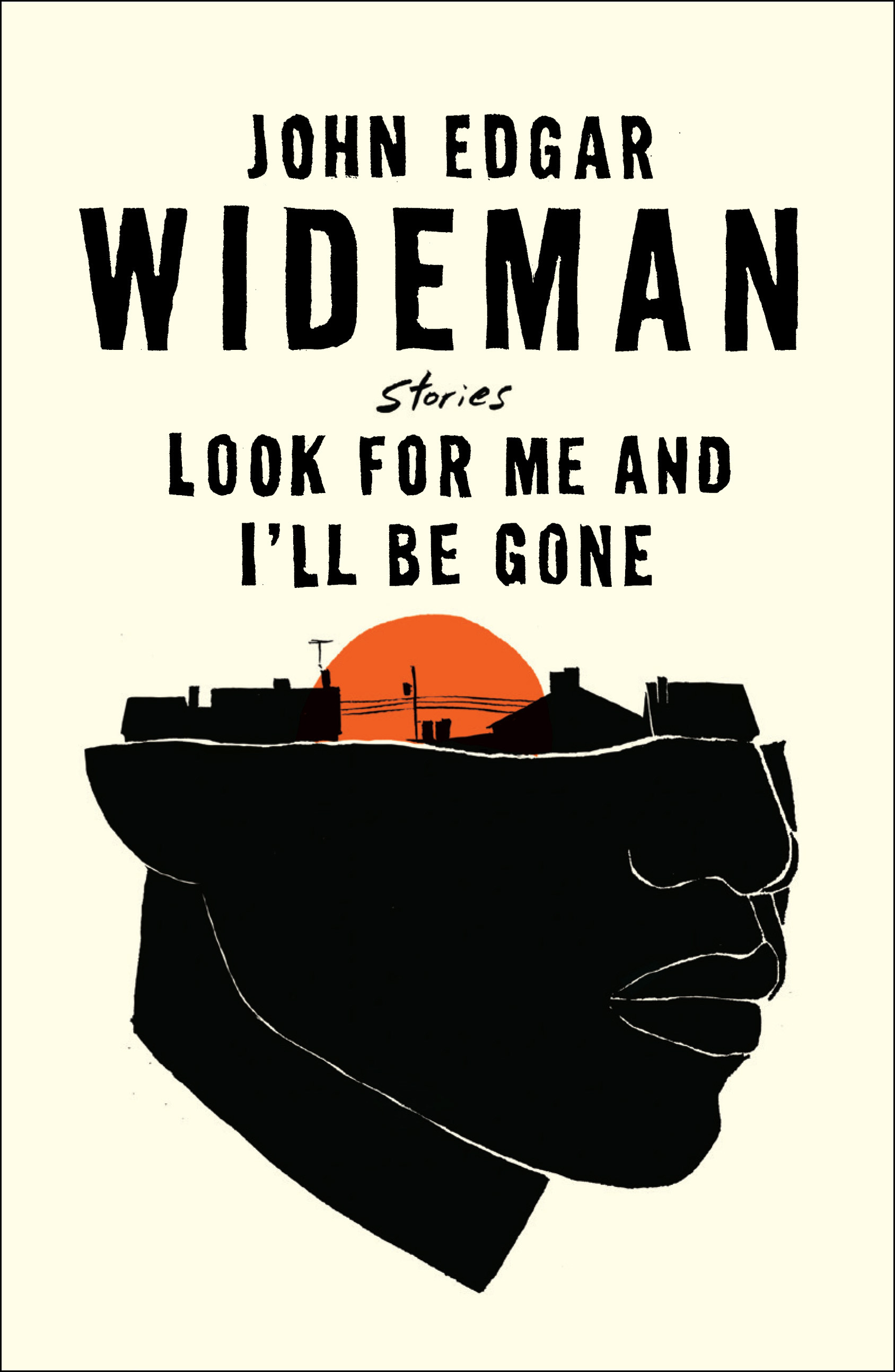

Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone, by John Edgar Wideman, Scribner,

318 pages, $26

• • •

My daddy commissary made it to commas

—Kendrick Lamar

Though you are a pro and sing for a living, do you still sing to yourself.

—John Edgar Wideman

Slave Lives Matter

In the correctional-facility visiting room where our narrator is meeting with his incarcerated brother, who is serving a life sentence, he has made sure to bring plenty of coins for the commissary-style vending machine, so that he can buy his brother some ready-made meals that drop down from the clawed cylinders of the machine into the abysmal hunger. He heats them up with the soft radiation of a microwave, and his brother eats appreciatively while they speak through the bulletproof plexiglass of doom and communion. Guards peer in on them periodically, reminding everyone that this is not a reunion but a long, wide-awake funeral. Trickster myself, but not beyond being tricked, the narrator concedes later. Hallucinating roads to abolition will not free us, his tone suggests. Abandoning the dream of abolition for the unapologetic reality of here-and-now might.

Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone, a short-story collection that draws fluidly from his personal life, is John Edgar Wideman’s extended farewell to outrage, though he’s never been given to gratuitous or reductive displays of that outre rage, as he renames it here. In its place, throughout Look for Me he beckons reconciliations with lost lovers, friends, children, siblings, would-be associates, and ruins and histories and futures. The book’s style is so deceptively modest it stares you down and waits for you to realize it’s cut your heart out while you coasted along on the calm surface of the syntax into a seething indictment of every aspect of society. Wideman’s is the most effective kind of indictment because he does not deploy oversimplified abstractions or blame nameless structural demons for the wrongs of the world. He offers himself and all that he loves as the evidence of things not seen but felt and suffered and overcome. He lets us into his prison, his “death row,” his lifelong trial, and the bleak turmoil of each anticlimactic verdict.

Tilting with Shadows

Wideman’s tone possesses a measured dignity that only a vague but palpable humility bordering on self-loathing corrupts. When he is less strategic and succumbs to a prevailing childlike awe toward his own experience objectified as fiction, it’s just as honorable and considerate of his needs and the reader’s. The cruel balancing act between imagination and reality is the protagonist in these stories; what he decides to remember dictates what he is capable of inventing. The title itself even plays with this synergistic relationship between the I and its ghost—Wideman searching for himself in inventions that he hopes will disappear him and absolve him.

What he most remembers and is incessantly haunted by is the United States criminal justice system. Each character and version of Wideman we meet here is one of its victims or a culprit in making it so brutal. A son goes to jail in Arizona for a clumsy unintended murder, a friend is jailed for killing and mummifying his woman, a former president is set to be executed for reckless and bloodthirsty overuse of the death penalty, though we find out this is just an idea for a television series. And then there’s the brother, in for petty theft turned worse but eventually freed. They reunite in Penn Station after his release, and there is heartbreaking confusion about how to navigate that underground labyrinth. Our narrator hopes they can ride the subway together and go on an adventure, but then sees his brother’s struggle to walk, a stifled arthritic gait, and hails a taxi. They eventually make it back to a living-room couch in the narrator’s home, and his brother announces it’s the first time since his release that he feels free. Wideman is one of the deeply relatable writers so devoted to and in love with his family that he betrays them, tells all of their secrets because secrets are the one thing they collectively have sovereignty over. Secrets, unadorned by fetish or hyperbole, turn the residue of being criminalized and locked up again and again into an intimacy and bittersweet means of bonding.

Everyone we encounter in Look for Me is suffering, their world is falling apart, gasping, and while some aspect of Wideman feels responsible, even for simply living to tell or imagine it, he feels equally resigned to love what is, as it is. He despises and resents what deserves resenting with a similarly blunt equanimity. He achieves all of the benefits of smugness without being smug, through relentless attentiveness, and by holding it together well enough to present the aching details made available by his attention, like the way the narrator’s son perks up when a Freddie Jackson song comes on the radio, as they’re in the car on the way to his sentencing. Music is always intervening here, aiding and disrupting the search for a new version of something like the self that threads through these tales. The benefit of his aloofness in the presence of so much musicality of thought and deed is space to exhale between notes and pitches, the way Miles Davis plays ballads with his back to the audience so you absorb the tone and not just a symbol of it. Wideman deftly avoids becoming his own celebrity witness.

Black Oblivion

Race. run. Or Maybe if you leap, water more like a fist in the face and knocks you out, he contemplates. Wideman does not run from racial identity but he is a little numb, as many of us are, to facile abuses of his skin. His held-back angst has to go somewhere, however, and it goes where it’s safest, to black women. He devotes an entire story toward the end of the collection to the bodies of black women, specifically to fat. He has withheld blatant meltdown, channeled it into a story that takes the form of a letter, or the strange bond between a black and a white missionary, or the lapis lazuli skin of the narrator’s French wife, but here it comes, black women are fat and dying, being fattened for the kill, he assures us, witnessing a crowd of them gathered on a Manhattan street.

These allegedly self-sabotaging strangers and the protagonist’s lapis-skinned wife are suddenly two poles of an imagination struggling to release itself from the prison of race and the prison of incarceration, through objectification of femininity, a porous concept onto which he projects his stray angst. Black womanhood is capacious and generous but not this easily scapegoated. The story moves hesitantly from weight to a family of innocent black women face down on concrete as police check their license plate, another case of mistaken identity. We could say Wideman is hardest on the ones he loves and needs the most, we could repeat Look for me and I’ll be gone. There’s no reason to harbor bitterness and outrage toward language that yearns to dispel it, no reason to assume these abolition stories wouldn’t hold some captive who they aim to break free.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa will be out next month.