Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Dreams, visions, and micro-contexts: a new show at the Drawing Center limns the outer reaches of our known world.

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, curated by Olivia Shao, the Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York City,

through February 1, 2026

• • •

Art has been hibernating lately—and that might be okay. Life is so large right now that it’s hard to imagine art scaling itself to meet the moment. Artists are out there, but, shadowed by national terror, they don’t quite know where to go. Meanwhile, art institutions waffle between crisis and stasis: galleries are closing ranks, and museums seem reluctant to imagine new ways of seeing. It makes sense, then, at times like these, that one might be tempted to step outside, look into the skies, and wonder if there is, in fact, anything else out there.

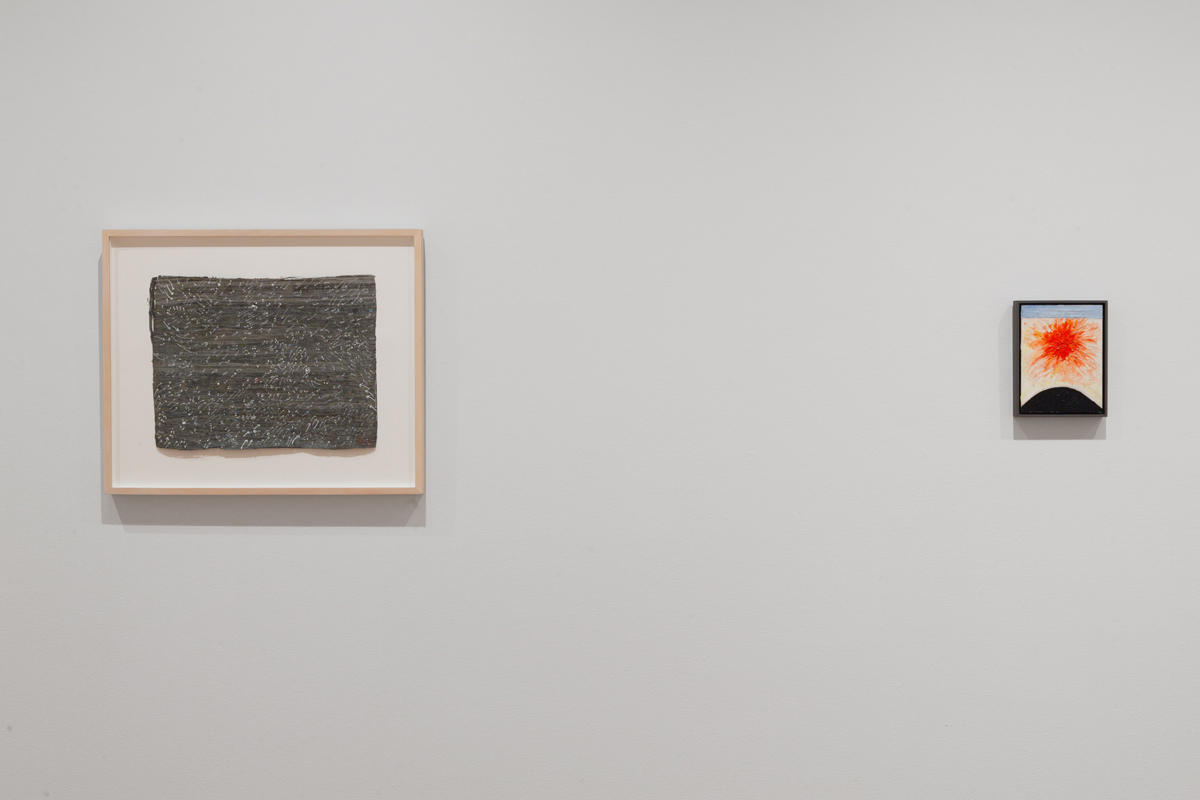

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured, left: attributed to He Nupa Wanica (Joseph No Two Horns), Visionary Drawing, 1920. Right: Char Jeré, Boundless, 2024.

The new exhibition at New York’s Drawing Center, Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, does just that, tapping into an increasing fascination with the occult, the far out, and the not-rationally explained. Where criticality once reigned, the mystical has come to follow. Time is suddenly measured in astral weeks and past lives. Asking someone their sign used to be a fun winky thing to do but has morphed into solemn inquiry. I’ve been resistant to grasp the pleasures of what feels like a tarot-astrological complex—my artist-heroes tend toward the likes of Dan Graham and Dara Birnbaum, who critically analyzed corporate architecture and prime-time television—but mulling over paranormal phenomena, I guess, might be a way to reconsider what we take to be normal, too.

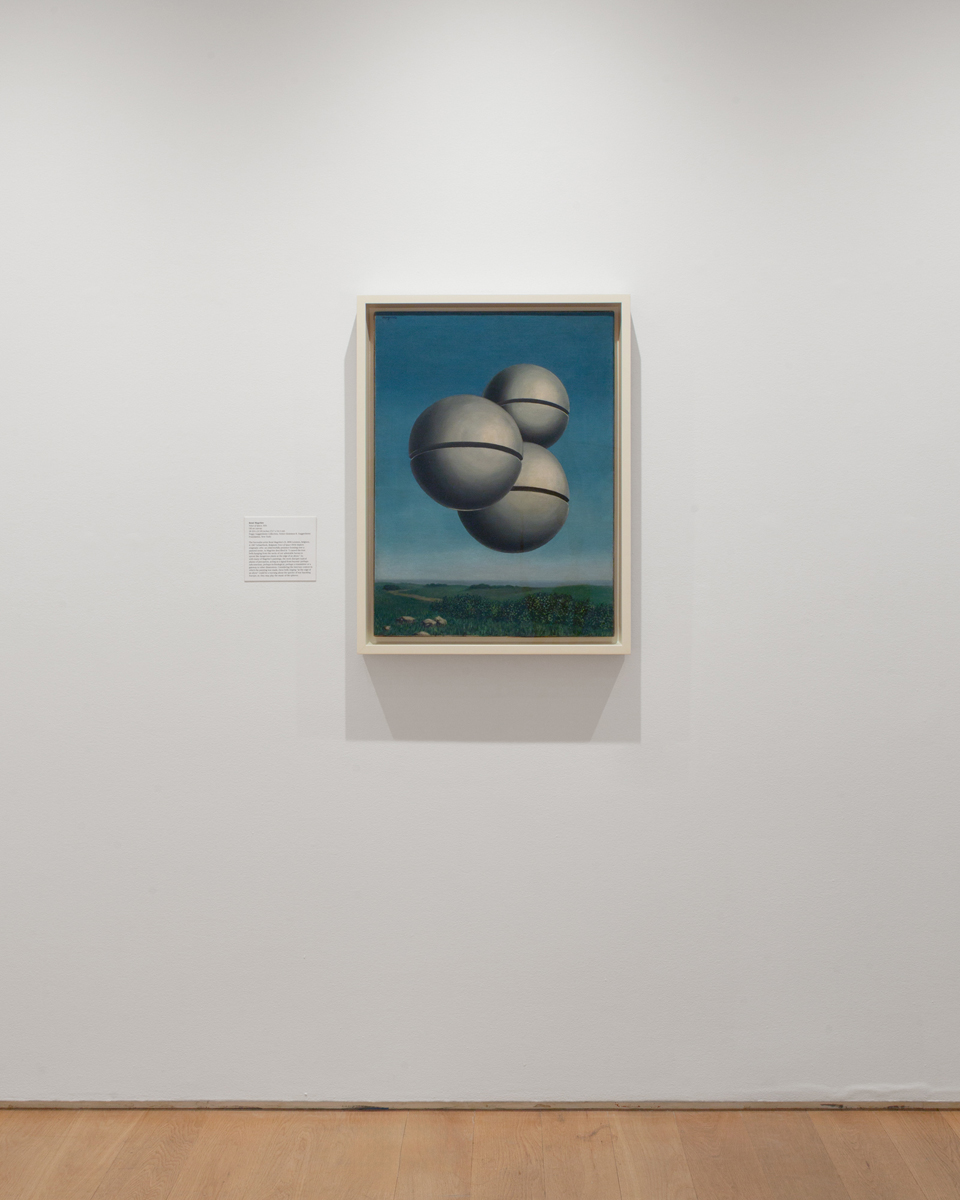

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured: René Magritte, Voice of Space, 1931.

Despite its esoteric interests, Voice is a traditional exhibition in many ways, consisting primarily of framed works on paper hung on white walls. A few things are in vitrines. Most items are small. A largeish iconic painting from 1931 by the Surrealist René Magritte, which lends the show its name, tips the scales, and slightly overwhelms the rest of the art. It also sticks in the mind—three big silver orbs, scored on the circumference, hovering over the Belgian (?) countryside. Apparently, the floating structures are meant to be bells, and so the eerie idea of silent music invades the scene, but it also makes one wonder about the meaning of voice in the show’s title. If space speaks through the ringing of bells, is it a language we can understand, if there’s even a language there at all? Can there be a voice that doesn’t say anything?

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured, right: Jutta Koether, Untitled, 1984.

Magritte is so dry. Is this a dream? A vision? A theory of the universe? Or simply unapologetic kitsch? These works run the gamut of belief and sincerity, which may or not map onto different cultures and contexts. There are folks who had real visions (a beautiful drawing from 1920 of a pockmarked blue hand), and then there are German contemporary artists. So, when you’re walking through the exhibition, there is a lot of recalibrating to do; one has to make micro-contexts constantly for different cases. Does Jutta Koether, a painter with deep roots in the Cologne art scene, have visions like He Nupa Wanica (Joseph No Two Horns), a Hunkpapa Lakota artist, or does she just dream of having them? Is that desire also a form of belief?

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured, far left: Trisha Donnelly, Untitled, 2025.

Voice of Space is tucked in the narrow room at the back of the Drawing Center and in the institution’s basement. In the main gallery, there is an exhibition of drawings by the San Francisco–born artist Trisha Donnelly. The two shows have things in common in terms of tone and style of presentation, and the connection is underscored by the inclusion of works by Donnelly in Voice—one additional drawing and a soundtrack of bells, a seeming attempt to unlock the ringing in Magritte’s painting. Donnelly’s drawings, however, feel less paranormal than their compatriots; rather, they look like preemptive evidence of an imminent post-human condition. Full of bird skulls and pelagic cartilage, they communicate the idea of a world after us, not beyond us. Everything here has the density of bone, knuckle, and (heavy) metal. The two exhibits converge, however, in their skepticism about language, a hallmark of Donnelly’s practice. Her press release begins with the words “the unspeakable” and then briefly repeats some gnomic wisdom from the Tao Te Ching. (Bells ring.) For someone less suspicious of language than Donnelly, her reticence can be a hard pill to swallow; it also reinforces a traditional division of labor: artists see, critics expound. (Might there also be a counter exhibition lurking here about people who talk incessantly about seeing UFOs? All those long, drawn-out theories?)

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured, center foreground: Isa Genzken, Weltempfänger Daniel (World Receiver), 1990.

At the end of the day, Voice of Space might be an exhibition that you visit in order to find a couple things to think about later. (For an extra chance to mull it over, pick up the handsome catalog with essays by curator Olivia Shao and artist-writers Paul Chan and Mark von Schlegell.) It was great to see a sculpture, for example, from Isa Genzken’s series World Receivers, a stereo-shaped brick of concrete plugged with antennae, in an exhibition about the beyond, because it has the effect of expanding the scale that Genzken is typically thought to work on, what her sculptures might be able to receive. I was also excited by the contributions of Char Jeré (an artist I didn’t know beforehand), who makes little device-collages out of balloons, sandpaper, and library cards in the style of Robert Filliou, which open up onto ideas of what the artist calls Afro-fractalism.

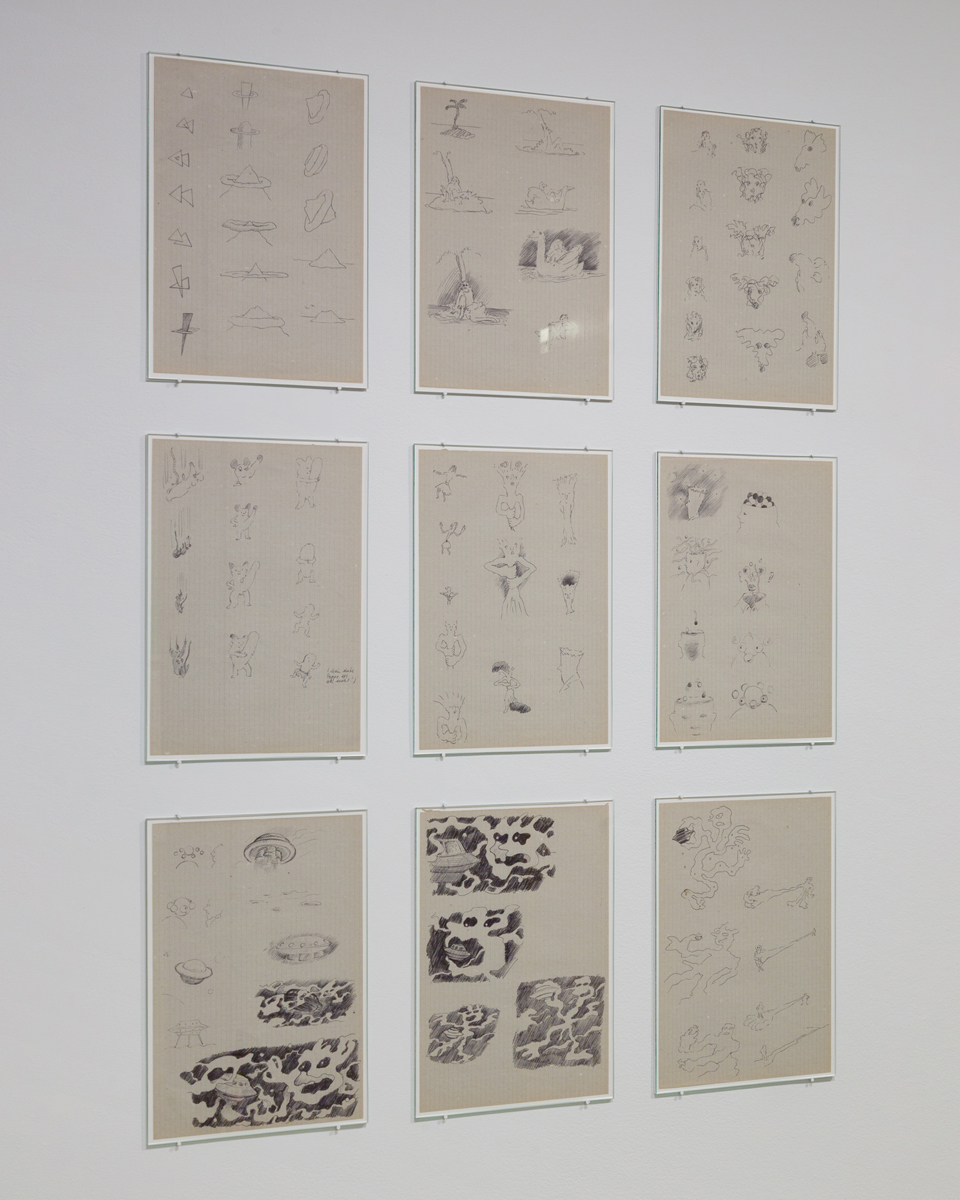

Voice of Space: UFOs and Paranormal Phenomena, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna. Pictured: David Weiss, Untitled (Wandlungen), 1975.

My favorite, however, is a series of drawings on nine sheets of graph paper by the Swiss artist David Weiss from 1975. Weiss, who passed away in 2012, was an endlessly inventive and playful draftsperson, his line squishing and squeezing into all manner of form, but often making its way into a wry space between the banal and the cute. There are depictions of UFOs here, natch, kitted out in their best 1950s comic-book incarnation, but there is also a hilarious sequence of a small furry gremlin celebrating his oversize penis only to turn into his penis at the end. I wouldn’t be so bold as to try and connect the dots between these pocket narratives of metamorphosis. Do they hang together meaningfully, or are these just cracked visions from the cultural unconscious that flickered out of Weiss’s pen? The same question applies to Voice of Space as a whole. Does the exhibition really present “a universal metaphor for contact between the known . . . and the unknown,” as the catalog claims? I imagine some visitors will be genuinely transported. Others will see cultural responses to unidentified phenomena. Some will vibe deeply, touch the beyond. Others will spy appropriation, reconsider the alien. And never will they meet. It’s destabilizing to think how little common ground there is beneath us. Even on earth!

Alex Kitnick teaches art history at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.