Laura McLean-Ferris

Laura McLean-Ferris

French theory’s influences ripple through the development of American art in a show at Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American Art, Francophone Thought, installation view. Courtesy Palais de Tokyo. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Pictured, far left: Firelei Baez, Spiralism (or an understanding, sun minded), 2025.

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American Art, Francophone Thought, curated by Naomi Beckwith with James Horton, Amandine Nana, and François Piron, assisted by Vincent Neveux, Romane Tassel, and Morgane Padellec, Palais de Tokyo, 13 avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, France,

through February 15, 2026

• • •

“French Theory” is an American term from the 1970s, an amalgam binding together literary critics, philosophers, and psychoanalysts such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Jacques Lacan. With the tang of a fashion or food trend, it suggests a shared style or methodology among its chief actors that did not really exist. However, it is now fair to say that during the “Years of Theory” (as Fredric Jameson called them), charged, analytical texts originally written in French rippled through the arts and humanities, as well as through studios, magazines, even clubs and parties. Tracing the effects of these ideas in the US, ECHO DELAY REVERB: American Art, Francophone Thought opened this fall at Palais de Tokyo as part of a “Carte Blanche” invitation to Naomi Beckwith, deputy director and chief curator of the Guggenheim Museum, New York, and artistic director of documenta 16.

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American art, Francophone thought, installation view. Courtesy Palais de Tokyo. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Beckwith’s broad thesis—and broad it is—is that “French Theory” influenced, or was responsible for, the development of several strains of American art. Cast in this exhibition’s light, the origin of a movement such as institutional critique can be found in the work of post-structuralists like Michel Foucault, who traced the way power has been accumulated, maintained, and transformed as it passes through institutions. If institutional power can be constructed, it can also potentially be deconstructed, or at least there can be a “displacement of givens,” as artist Michael Asher so finely put it.

David Wade, Michel Foucault and Michael Stoneman in Death Valley in California, May 1975. Photo: Simeon Wade. © David Wade.

You won’t find much in the way of “theory” in this show beyond the kind of brief summation I just gave of Foucault’s thinking or a smattering of famous phrases such as “The Death of the Author.” Most ideas are précised in a single sentence or a quote on the wall in the introductory zones that introduce five distinct sections—“The Critique of Institutions,” “Geometries of the Non-Human,” “Abjection in America,” “Desiring Machines,” and “Dispersion, Dissemination”—which are lined with red wallpaper and illustrated with photos of French philosophers looking extremely cool (Foucault positively slays in huge white shades in a picture taken in Death Valley). Art marshals information very differently than writing, and no one wants to see an exhibition in which art “illustrates” theory, but this treatment of the source materials is a little cursory for my taste. Still, in this regard, the title was well chosen, if we take it to mean that complex ideas reverberate like fragmentary echoes among artists, who might absorb some of a theory’s tenets without reading any particular critical text. This is how culture moves, digesting and mutating like an organism.

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American art, Francophone thought, installation view. Courtesy Palais de Tokyo. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

In an elegant gesture, Beckwith begins by referencing Afro-diasporic writers such as Aimé Césaire and Édouard Glissant in the opening section, ‘‘Dispersion, Dissemination,” which immediately pulls the “French Theory” cliché away from its whiter names and instead emphasizes the bond between Black and postcolonial struggles from overseas Francophone countries and those of the US. The selected works, though made by artists appropriate to this theme, are not especially rich examples, however, and have a bit of a random commercial flavor: a small monochrome Julie Mehretu painting, Heavier than air (written form) (2014), and a large, spiraling canvas in pinks and blues by Firelei Báez, Spiralism (or an understanding, sun minded) (2025). Here, the show seems to ask rather inert objects to carry radical theories of disruption, dismantling, and destabilization.

Lorraine O’Grady, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Goes to the New Museum, 1981/2007. Courtesy the Lorraine O’Grady Trust and Mariane Ibrahim. © Lorraine O’Grady / Artist Rights Society (ARS).

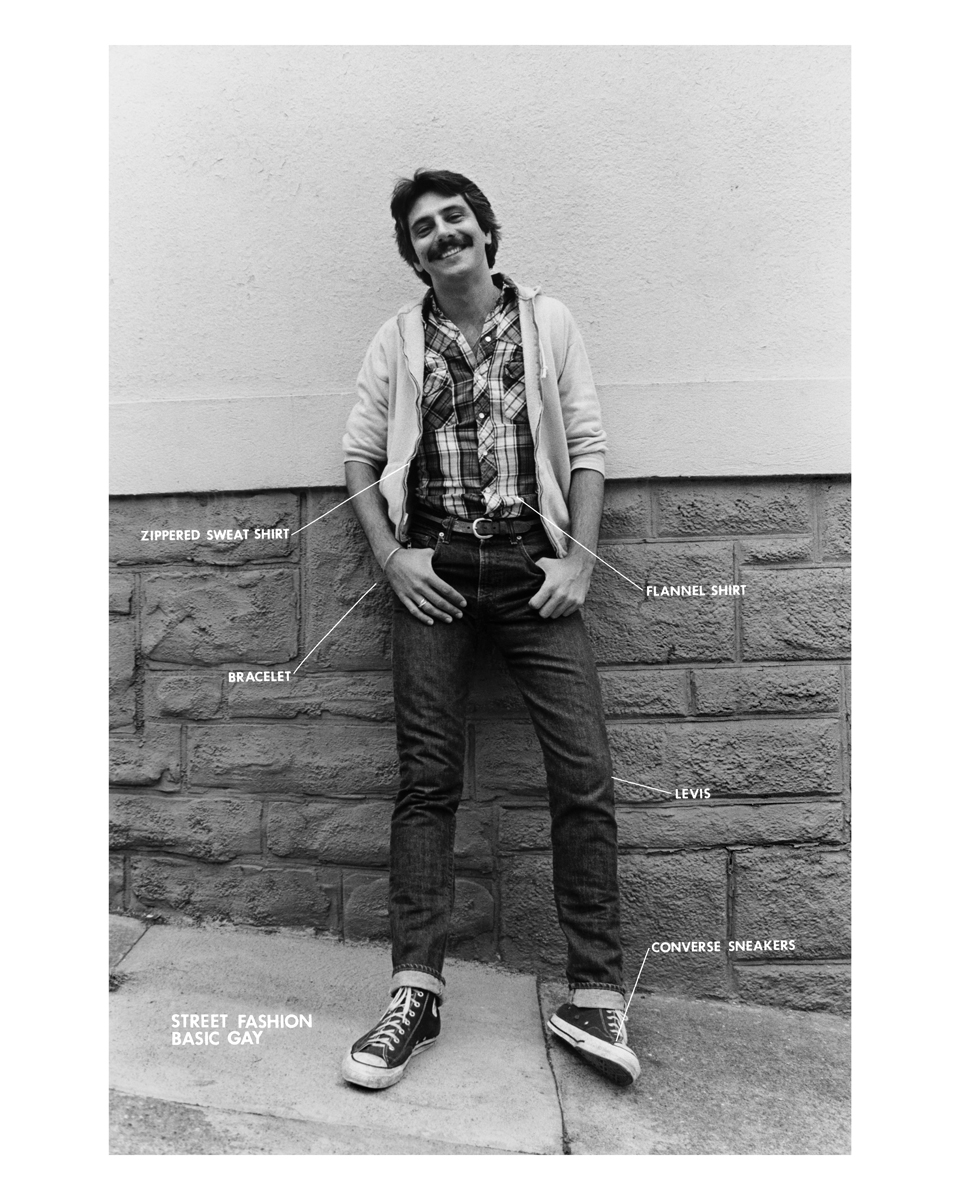

“Critique of Institutions” features a stronger selection of works, more characteristic of their genre. In Andrea Fraser and Jeff Preiss’s video May I Help You? (1991 / 2005 / 2006), Fraser gives a captivating and deranged gallery tour inspired by Pierre Bourdieu’s critiques of taste, while in Lorraine O’Grady’s performances as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1981/2007), the artist arrived at openings dressed as a beauty queen in a pointed burlesque of the compromises a Black artist might make to be accepted into a white art world. In “Desiring Machines,” we feel the influence of semiotics behind Hal Fischer’s Street Fashion (1977), where male sexualities such as “Basic Gay” are lovingly and campily staged in taxonomic photographs and then subjected to analyses that point out the significant placements of earrings, handkerchiefs, and so on.

Hal Fischer, Street Fashion: Basic Gay (from the series Gay Semiotics), 1977 (printed in 2014). Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant.

Frantz Fanon’s critiques of humanism are invoked in “Geometries of the Non-Human,” featuring reflections on some witty, troubling performance works from the 1990s: engravings documenting Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit The West (1992–94), in which the artists, purporting to be from an undiscovered tribe, displayed themselves in a cage, and photographs from James Luna’s The Artifact Piece (1987), in which he presented himself as a live exhibit of an Indigenous person. Finally, “Abjection in America,” with works by Mike Kelley and Cindy Sherman, reminded me too much of the concluding section of Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss’s Formless: A User’s Guide, though Pope.L’s drawings on Pop Tarts from 1998 added a new and powerful variation on the theme. Fusing Pop Art to abject forms of ingestion, these strange consumables become vehicles for cartoon faces with racist overtones.

ECHO DELAY REVERB: American art, Francophone thought, installation view. Courtesy Palais de Tokyo. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Pictured, far left: Cindy Sherman, Untitled (n°142), 1982. Center, foreground: Mike Kelley, Spread Eagle, 2000. Far right, on right wall: Pope.L, Trinket, 1998.

On October 23, Cameron Rowland’s contribution, Replacement (2025), for which he had replaced the French flag hanging from the Palais de Tokyo with that of Martinique, was removed by the museum the day after it was installed, on the grounds that it “may” be illegal to fly a flag asserting any political, religious, or philosophical opinions, as public services must display “neutrality.” It’s debatable whether flying the flag of a French territory suggests a position, and Rowland and his gallerist Maxwell Graham, who consulted with lawyers on the issue, have disputed the decision. It’s possible that the Martinique flag’s resemblance to the Palestinian one played a role in the museum’s actions, given the latter’s power to inspire terror around political neutrality. Regardless, the removal of an artwork tends to inspire outrage and attention, and it could seem like this was the intention behind Replacement (I have been assured in a statement from Maxwell Graham Gallery, as a representative of Rowland, that this is not the case).

But ECHO DELAY REVERB was also a little provocative by design: in an interview with Beckwith available onsite, the curator suggests the show pushes back against French accusations that European politics have become “Americanized” by ideas relating to race, sexuality, and cultural origins. “I want to remind people in France: this is your fault. Some people think ‘wokeism’ comes from the U.S. but in many ways it is profoundly French.” Hmm. It would be tiresome to get into this at length, due to the demented discourse around the word “woke,” but this seems misguided and a bridge too far, non? However, she does go on to say that she sees a “rejection of certain terms for thinking about personhood in France. Why is it so difficult to talk about race? Why is it so hard to reconcile the colonial legacy with the idea of Frenchness?” Indeed.

Replacement . . . there’s a lot of fear embodied in the title of Rowland’s work, not least in its terrible echo of white nationalist replacement theory, a miserable form of French conspiracy theory that has also made traction in the US. While it’s hard to read the removal of the flag as anything other than a sign of France’s domineering yet anxious relationship to its own citizens of Martinique, who include Fanon, Césaire, and Glissant, it is also just one more indication that museums have become scenes of fracture over the split interests of artists, publics, and patrons. The international solidarities that ECHO DELAY REVERB sketches out, as well as the yearning or even nostalgia for serious thought on display, might also be taken as expressions of desire for the kind of institutions that might be needed today, ones that might hold together, even in a climate of fear.

Laura McLean-Ferris is a writer and curator based in Paris. Her criticism and essays have appeared in Artforum, ArtReview, Bookforum, frieze, and Mousse, among other publications, and she was the recipient of a 2015 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. Formerly she was Chief Curator at Swiss Institute, New York, where she worked from 2015 to 2022.