Tausif Noor

Tausif Noor

Private rituals, public self-image: a museum show by the multimedia artist.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: Big Wash, installation view. Courtesy Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo: Carlos Avendaño.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: Big Wash, curated by Karen Patterson, Fabric Workshop and Museum, 1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia, through

June 6, 2021

• • •

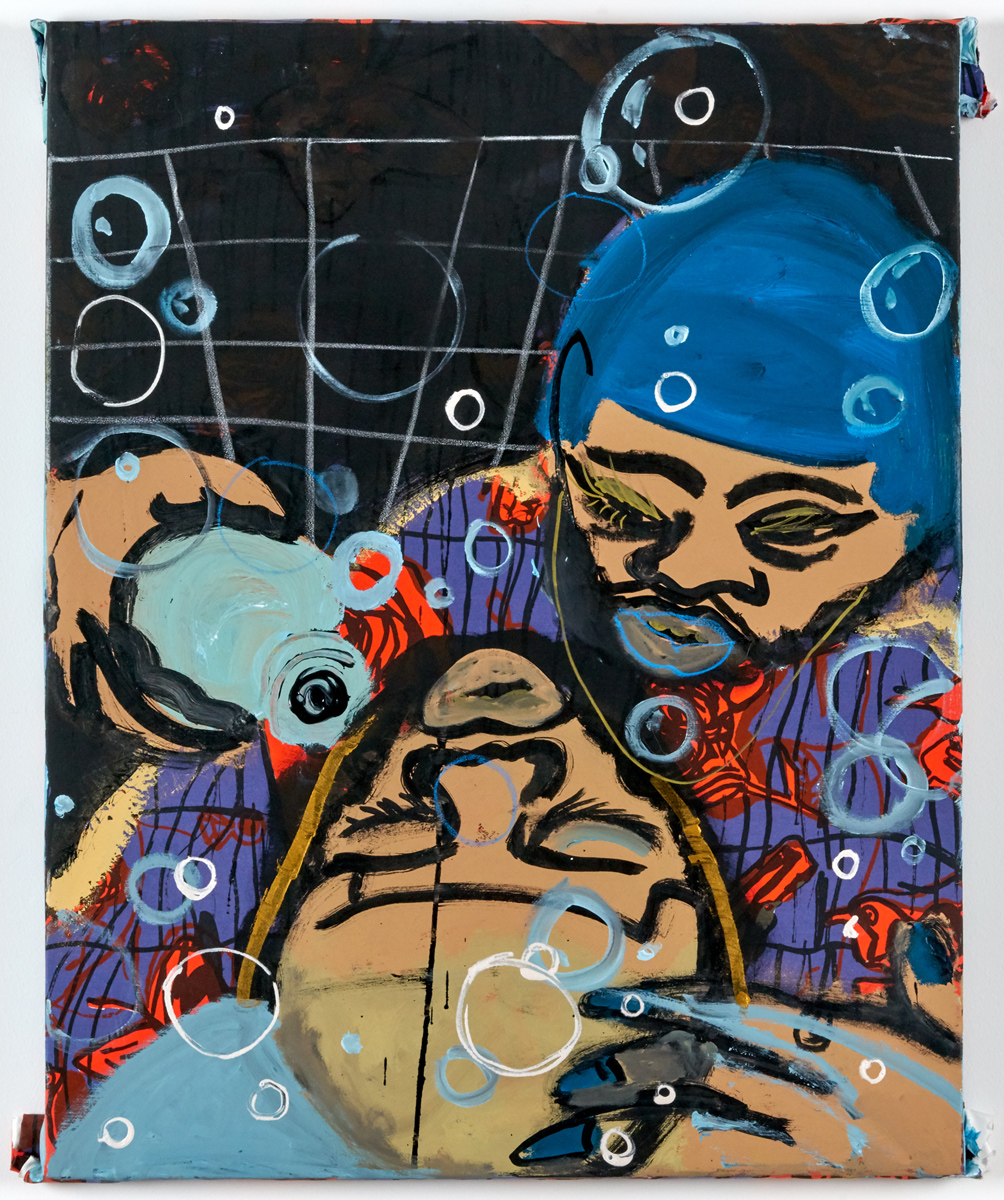

Maximalists rejoice! Jonathan Lyndon Chase has offered up a much-needed dose of exuberant, unabashedly queer visual pleasure in the form of collaged paintings, drawings, fabric sculptures, videos, and installations, sixty-six of which crowd the second floor of the Fabric Museum and Workshop in the artist’s first solo museum outing. Originally slated to open last November and delayed until January, Big Wash marks a kind of homecoming for the Philadelphian multimedia artist, whose ebullient works celebrate the rhythms of Black queer life, plumbing the rich legacy of Black popular culture, early 2000s digital aesthetics, and the urban terrain of North Philadelphia to defy any singular notion of queer representation. Instead, Chase, who has exhibited in a roster of increasingly high-profile galleries and fairs, works fluidly across various registers of figuration and abstraction with a dazzling degree of formal experimentation to present images of Black queer subjects in all of their complexity.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: Big Wash, installation view. Courtesy Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo: Carlos Avendaño.

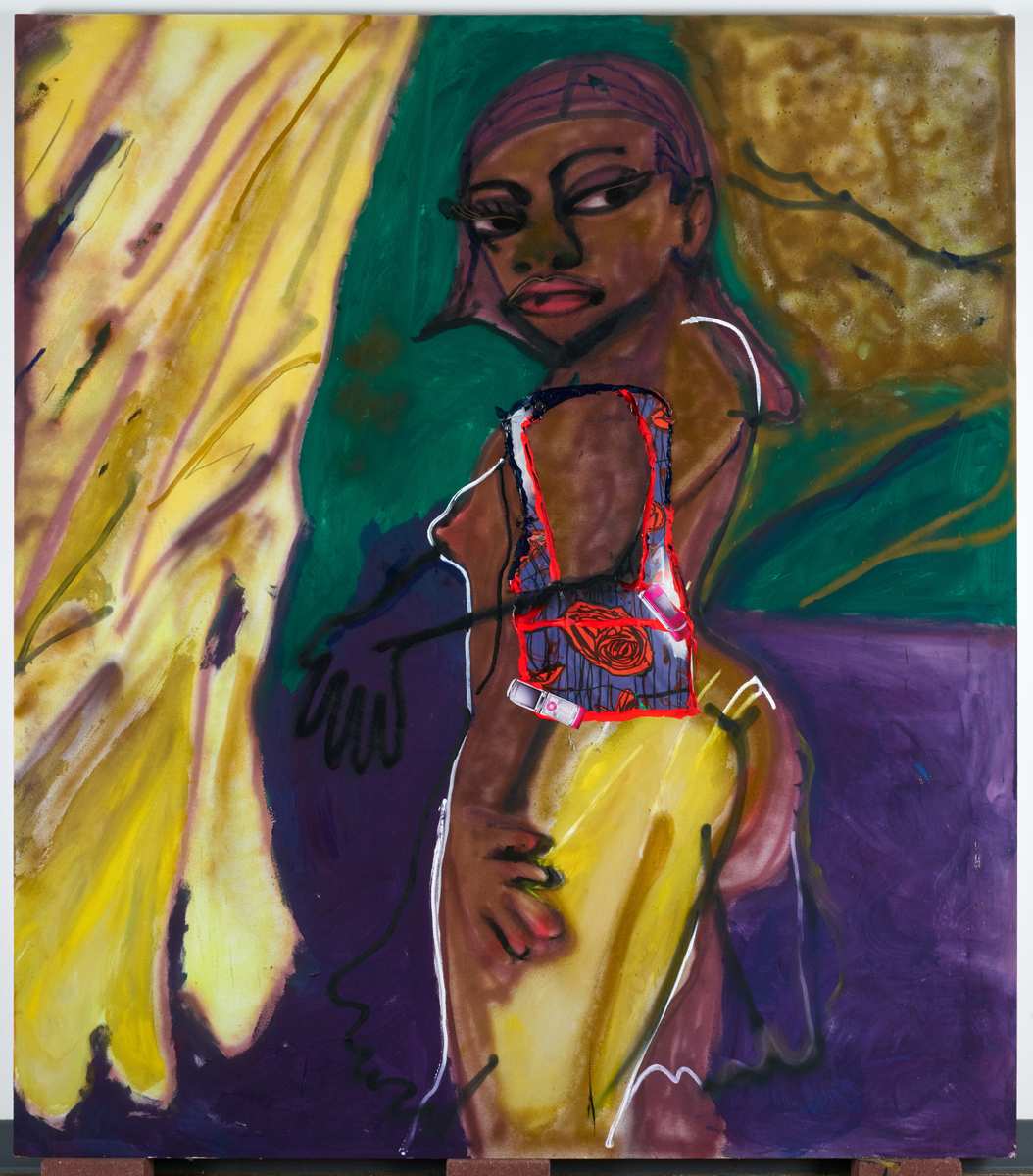

As suggested by its title, as well as the two bubble-emitting washing machines sitting atop a black-and-white checked linoleum floor that runs along the center of the gallery, the focal point of Big Wash is the physical and social space of the laundromat. Here, the sundry material of private life enters public, communal activity, evidenced by the boxer shorts pinned to a clothesline between two wire laundry carts. Nodding to the Fabric Workshop’s legacy of artist residencies, curator Karen Patterson invited Chase to silkscreen custom-designed yardage, resulting in bolts of purple cloth emblazoned with sketchy red-orange roses, camouflaging portraits of individual Black queer figures culled from images in the artist’s many binders of queer ephemera. Titled Bending $ag, the pattern was used to fashion the aforementioned boxers, pairs of which were also distributed to Chase’s friends alongside bouquets of baby’s breath—a gesture that speaks to the artist’s propensity for building networks of queer companionship. The printed fabric appears at various points throughout the exhibition: it’s used to make a bag slung on the shoulder of a femme figure in the massive canvas hang up vibrating purse (all works 2020); it serves as the backdrop against which a figure inspects the curving pattern of their hair, rendered in thick, glittery turquoise paint in Wave Check.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase, hang up vibrating purse, 2020. Watercolor, acrylic, fabric marker, pen, collage, spray paint on muslin, 84 1/2 × 74 inches. Courtesy the artist and Company Gallery. Photo: Alec Smith.

Much of Chase’s work toggles between the intimacies of private rituals and the fashioning of a public self-image from the seemingly limitless aesthetic cues of the external world. The collaged paintings hung along the walls of the gallery situate the artist’s queer figures in domestic interiors such as kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms, where they evince a fulsome subjectivity, reveling in their self-presentation and adornment and partaking, alone or in pairs and groups, in the quotidian activities that define everyday life: eating meals, showering, sleeping, fucking. Rinse depicts a lover tenderly washing their partner’s hair in a kitchen sink, the fingernails of the washer decorated with bright blue lacquer. Beneath the painting, the artist has written a confessional poem in looping cursive: “Never forget what you / Said to me in the reflection / Of your bathroom mirror/ Rinsing your wishes away / Leaved me dry of love.”

Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Rinse, 2020. Acrylic, marker on cotton sateen, 29 × 23 inches. Courtesy the artist and Company Gallery. Photo: Alec Smith.

Throughout the collaged paintings and drawings in this exhibition, the manifold dimensions of Blackness and queerness emerge commingled, rather than as discrete and independent signifiers, proof positive of the artist’s insistence on a both/and complexity when it comes to identity and its representation. In Chase’s renderings, characters who upon first glance seem to evoke standard conventions of Black masculinity—such as the titular figures in Video Bois, or the protagonist in Where you at?, bedecked in gold chains and clad in sagging pants—betray those very norms through their suggestive poses and the makeup adorning their faces. This quality is formally echoed in Video Vixens, where a combination of acrylic, oil stick, marker, and spray paint seems to locate the figures, their hair painted in shocking lime green, as shifting between the work’s dark background and foreground.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Video Vixens, 2020. Acrylic, oil stick, marker, collage, spray paint on muslin, 72 × 60 inches. Courtesy the artist and Company Gallery. Photo: Alec Smith.

In facture and style Chase’s cut-and-paste approach to Black and queer identity is reminiscent of Mickalene Thomas, Romare Bearden, and Frederick Weston, as well as a younger cohort of artists such as Devan Shimoyama and Troy Michie, each of whom mines mass media and history to render the queer Black figure as prismatic, resplendent in its multidimensionality. What marks Chase’s style as particularly distinct is their yen for the errant detail that underscores the cacophony of material excess: a single brick sitting on the gallery floor, painted green with “$100” scrawled on its face; the plastic canister of Lawry’s seasoning salt that sits atop the canvas of Fresh mopped kitchen floor.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: Big Wash, installation view. Courtesy Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo: Carlos Avendaño.

Indeed, the exhibition inventories a great deal of stuff, effluvia that could be found at Forman Mills, the regional discount retailer whose logo appears on multiple works. In this way, Big Wash is also a kind of love letter to Philadelphia, the environment that has shaped Chase’s practice and, in many ways, their sense of identity. On surfaces that include canvas, floral-printed cotton sateen sheets, and the red stretched polyester that may have once been a do-rag, the artist has attached such tawdry items as defunct flip phones, gold bamboo earrings, printouts of Juicy Couture logos, glittery stickers—all jumbled together in a fantastic assemblage.

Jonathan Lyndon Chase: Big Wash, installation view. Courtesy Fabric Workshop and Museum. Photo: Carlos Avendaño.

Mining material culture, Chase suggests that identities are porous, subject as much to external influence as internal self-actualization, a process that is messy, erratic, continual. Consider the materials listed in the installation Past few days, I need to hose down, a painted Styrofoam mannequin head laid atop a stack of folded towels that sits in one of the laundry carts: urine, cum, feces, sweat, soap, shampoo, spit, and tears. Together, these allude to the laundromat’s sanitizing function, yes, but they are also evidence of the artist’s conviction that to fully convey a person’s subjectivity, one is obligated to present the abject alongside the beautiful. “Bodies are gross,” Chase once proclaimed. “I’m after trying to talk about how bodies are complicated. It’s definitely having to do with desirability and being unapologetic and being raw and just sort of—we’re human.” With this eclectic, inspired exhibition, Chase has put Black queer humanity at the fore.

Tausif Noor is a critic, curator, and doctoral student at UC Berkeley currently based in Philadelphia. His criticism appears in Artforum, frieze, the Nation, the New York Times, the White Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications.