Philippe Parreno

Philippe Parreno

Cosmogony and the clown: on the occasion of Nauman’s

PS1/MoMA retrospective.

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts, installation view, MoMA PS1. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Digital image © 2018 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts, the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through February 18, 2019, and MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, through February 25, 2019

• • •

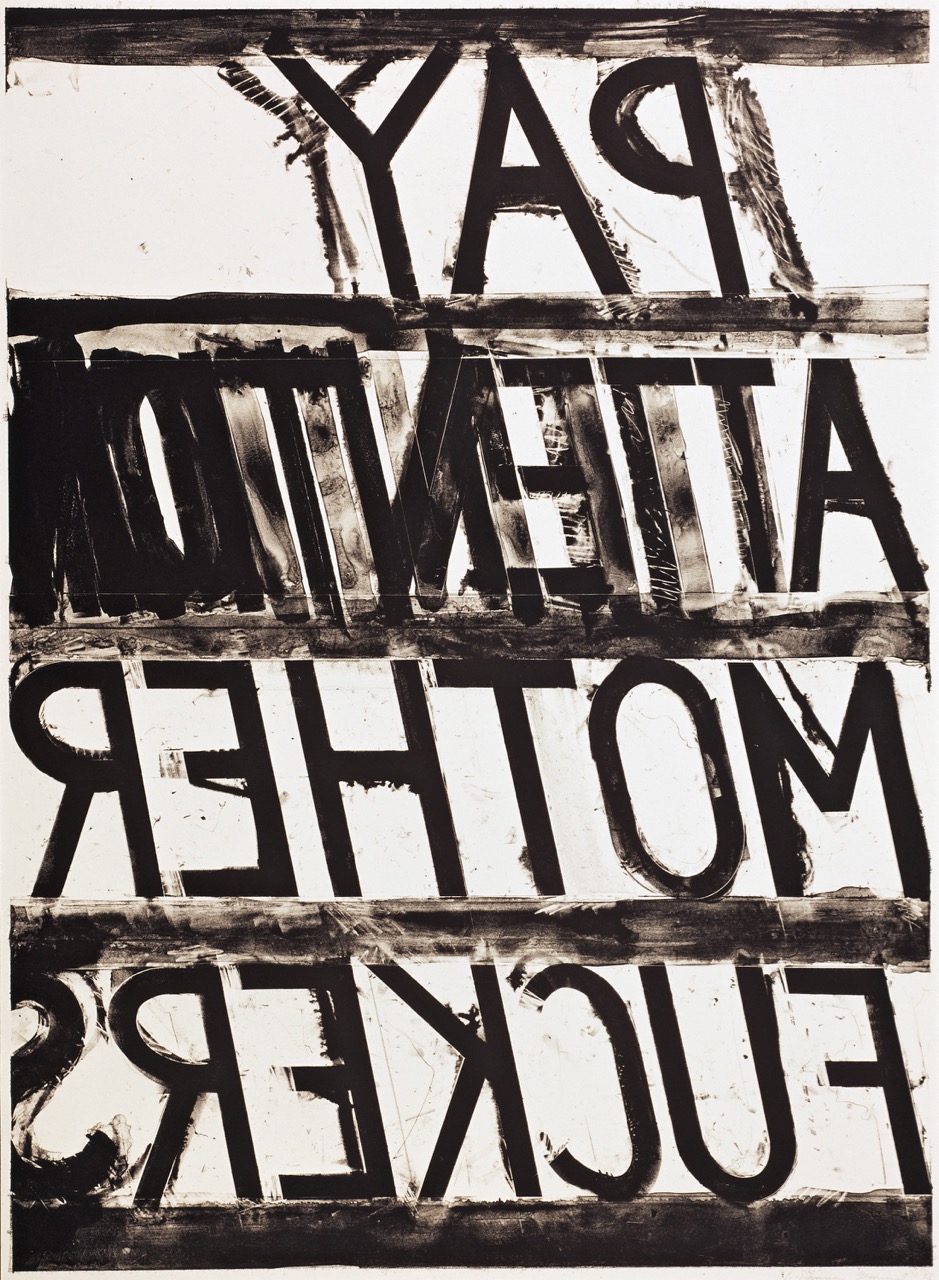

PLEASE

PAY ATTENTION

PLEASE

By using as an epigraph Bruce Nauman’s 1973 collage—a white ground containing the words “please pay attention please”—I want to emphasize a paradox, or more precisely, an absurdity. How can you quote a work of art?

Writing this review for 4Columns brings to mind a remark that Jean-Luc Godard made about the Cahiers du cinéma, “There is reviewing in a review.” We write reviews because we need to see something again, or because we want to view what we didn’t see the first time. Of course, an exhibition is also made to review. The show Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts, curated by Kathy Halbreich and Heidi Naef, made me review certain ideas, such as the relationship between words and images. There are images in the words and words in the images. It’s a never-ending story, even if for years we can sense the desire for an ending. In our culture, image and text are related; they are theologically and metaphysically linked. What makes us write is what has already been written, and what makes us love is what has already been loved. Like in tennis, we’re passing the same ball back and forth.

Bruce Nauman, Pay Attention, 1973. Lithograph, 38 ¼ × 28 ¼ inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Pay Attention, © 1973 Bruce Nauman and Gemini G.E.L.

The words used in a work of art may constitute the work itself, or they may float suspended as mere statements. As Robert Filliou said, “well done, badly done, not done.” Sometimes the text corresponds to the imagery, sometimes it doesn’t. The anticipation makes the situation almost farcical. It’s all a question of timing.

Bruce Nauman, Walk with Contrapposto, 1968. Videotape, black and white, sound; 60 minutes to be repeated continuously. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Image courtesy Sperone Westwater.

Nauman’s work contains patterns that develop in time through a strange ontogenetic process. Ontogenesis describes the progressive development of an organism from its conception to its death. In biology, this term can be applied to humans as well as nonhumans. We can also find it in the field of developmental psychology, where ontogenesis means the psychological development of an individual, and more generally, the structural transformations that determine the organization or the final form of a living system. Walk with Contrapposto has evolved over time. It was first a performance filmed in 1968, and now it has become an image filmed in

3-D. We’ve come full circle. I think that’s funny.

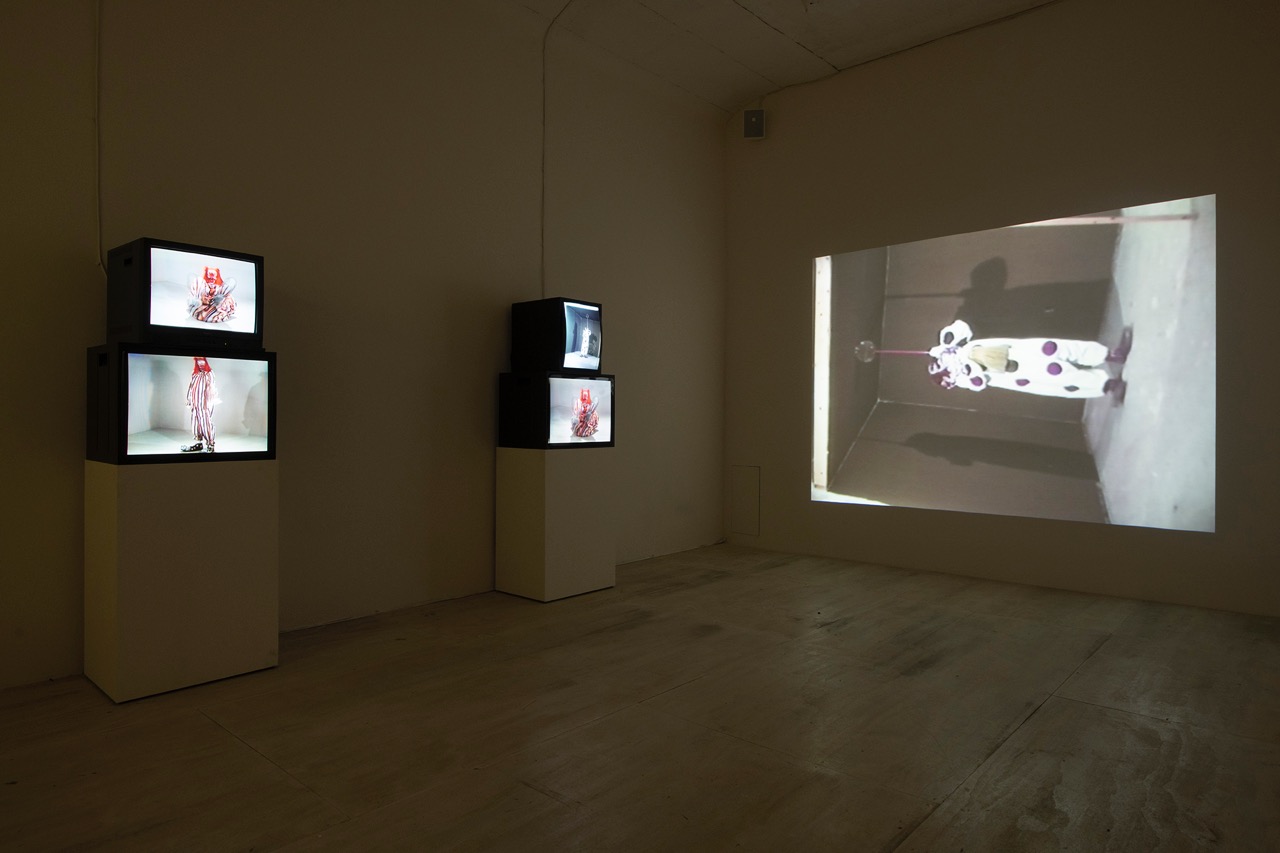

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts, installation view, MoMA PS1. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Digital image © 2018 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

No, No, New Museum (1987), a Nauman video that I saw through the window of the New Museum in 1987, shows a clown jumping up and down and yelling “no! no! no!”. It made me laugh for a long time, and I often re-see and re-hear the clown’s repeated stifled cries. His shouting was stifled first of all by the cathode-ray tube and secondly by the window, but I could still hear him. Did this confined character enjoy his status as an image or did he want to escape it? One thing was clear—this clown without a story was a prisoner of his frame and could only jump up and down eternally.

In his book on laughter, Henri Bergson explains comedy with his famous expression, “the mechanical encrusted on the living.” Something that happens once isn’t necessarily funny, but when it keeps happening, it becomes comical and uncanny. Excessive synchronicity is hilarious.

The real is without a double: it provides neither image nor relay, neither replica nor respite. In this way it constitutes idiocy. The word “idiot” means single, a particular individual, unique, unsplittable. Idiocy evokes the real. This is a far-off real because it is forever relegated to the mirror, and at the same time, it’s a nearby real because it is always in view. The intellect has an inherent temptation to replace the real with its double. What genius can produce and replace the real all by himself? The art of making desire and reality coincide is the definition of joy.

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts, installation view, MoMA PS1. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Digital image © 2018 Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

For Nauman, the genius is the clown. For Samuel Beckett, it’s the “hero.” For Jacques Tati, it’s Monsieur Hulot. For Charlie Chaplin, it’s the

Tramp . . .

In The Different Modes of Existence, the philosopher Étienne Souriau defines the virtual as one of multiple modes of existence. The virtual comes along with the imaginary and the real.

It may not be important after all whether an object exists or not; it’s a matter of its mode of description. Alain Robbe-Grillet offered one of the most convincing theories of description in writing, “The descriptions we make replace their objects for us.” Description simultaneously erases and creates the object. This for me is the virtual.

Well done! Badly done! Not done!

Strangely enough, we are still playing with the old question of “live” vs. “replay,” where reality is distinguished from fiction in the same way that a live event is distinguished from its recording. Today, streaming offers infinite degrees of slightly delayed broadcasting. Reality can write a film and a film can rewrite reality. Finding new scripts, new relationships, can allow us to see what we can’t usually see, the same way that people with synesthesia perceive what no one else can. There is an obsession with confusing vision with comprehension because everyone says “I see” to express “I understand.” In other words, what is real is not necessarily what is visible, it can only be what has been described.

Bruce Nauman, Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 1966, from Eleven Color Photographs, 1966–67/1970. Color photograph, 18 ¾ × 23 ½ inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Image courtesy Sperone Westwater.

Nauman’s retrospective depicts a time, our time. A time when we implicitly decide what is possible and what is impossible in our world. Perhaps this is how we define our world. We need to consider what it means to exist, what kinds of things exist, how they exist, what they exist in relation to, and so on. Language itself plays a crucial role in our perception of things and of the world. “In the beginning, there was the word,” says Alan Moore. Every metaphysics is a set of decisions on how best to order the chaos of mere existence; it is the form of a particular universe or cosmos. Cosmology is the discourse around the order of the cosmos. But as any good myth teaches us, underneath every cosmology there is a cosmogony, or a process of creation of that particular universe. Cosmogony is about the recreation of the real.

Bruce Nauman, All Thumbs, 1996. Plaster, component A: 10 × 5 ½ × 4 inches; component B: 9 ½ × 4 × 4 ¼ inches. © 2018 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society. Image courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater.

Time for magic?

In magic, there is no causality, there is an immediacy or, more precisely, an immediacy of power. There is a similar kind of immediacy or presence when you encounter an artwork. Souriau writes that an artist responds to the call of the work to be made. This does not mean that the work doesn’t exist, but that it has an unfinished existence. He uses a beautiful term to describe the artist’s response to the work’s request for fulfillment: “instauration.” Unlike familiar words such as “build,” “manufacture,” or “create,” instauration does not imply that the being or thing to be made is entirely determined or brought to life by the artist-creator. The notion of instauration indicates, or rather insists, that the artist takes on the responsibility of responding to the call of the work and devotes himself or herself to leading this being to a fuller or more real existence on another plane.

In the opening scene of Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige, an off-screen voice states:

Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called “The Pledge.” The magician shows you something ordinary . . . The second act is called “The Turn.” The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. Now you’re looking for the secret . . . but you won’t find it, because of course you’re not really looking. You don’t really want to know. You want to be fooled. But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough; you have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call “The Prestige.”

“The Prestige” is the moment when the unexpected occurs. This is the high point of the trick. In Bruce Nauman’s Disappearing Acts, images and words reappear, perhaps even call to be reviewed, on this other plane of existence.

French artist Philippe Parreno works across film, sculpture, drawing, and text, conceiving his exhibitions as a scripted space where a series of events unfold. He seeks to transform the exhibition visit into a singular experience that plays with spatial and temporal boundaries and the sensory experience of the visitor. Parreno is based in Paris, and his work has recently been shown at Gropius Bau in Berlin, Museo Jumex in Mexico City, the Rockbund Museum of Art in Shanghai, and the Tate Museum in London.