Simon Reynolds

Simon Reynolds

The Purple One’s Sign O’ the Times gets an expanded-edition reissue.

Sign O’ the Times (Super Deluxe Edition), by Prince, the Prince Estate / Warner Bros.

• • •

Back in the day, the default critical response to a double album was “would have made a great single album.” Sign O’ the Times was that unheard-of thing: the double that could have been an even greater triple. Released in 1987, at a career point (this was, unbelievably, Prince’s ninth LP) when artists are typically stuck in a rut and coming up empty, Sign frothed with fresh ideas, startling genre collisions, melodic panache, and sheer zest. The cornucopian overflow was even more remarkable given that almost all the instrumentation on the album was played by Prince himself, his backing band the Revolution having dispersed.

A triple album, titled Crystal Ball, is actually what Prince originally wanted to put out. But his record company, Warner Bros., felt this was more than the market could stand, especially as the Purple Rain superstar had slipped commercially with the modest-selling and patchy albums Around the World in a Day and Parade (the latter hitched to an abysmal movie, Under the Cherry Moon). With his vision only slightly leashed and corseted, Sign saw Prince surging to his imperial peak as an artist: taking risks but also scoring hit singles with the title track, “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man,” and “U Got the Look.”

The new eight disc plus live concert DVD revamp of Sign is not the triple that Prince intended, but more like a quadrupling or quintupling of the original eighty-minute album. I’m not sure there’s any masterpiece in the popular music canon that could withstand such inflation. Nevertheless, the Super Deluxe reissue has become a standard industry format, often commemoratively tied to the twentieth or fortieth anniversary of a classic’s original release. Legendary albums are spruced up sonically with yet another remastering and bulked up with disc after disc of studio outtakes, alternate versions, demos, and live recordings. These lavish repackagings are primarily an incitement to reconsumption aimed at hardcore fans happy to pay for a treasurable box set stuffed with illustrated booklets and memorabilia (such as the reproductions of handwritten lyrics in this supersized Sign). But the expanded editions also reach first-time listeners through streaming services, which means that increasingly the initiating experience of a classic album isn’t the focused brilliance of its original incarnation but a sprawling banquet that straggles on through course after course of steadily more indigestible fare.

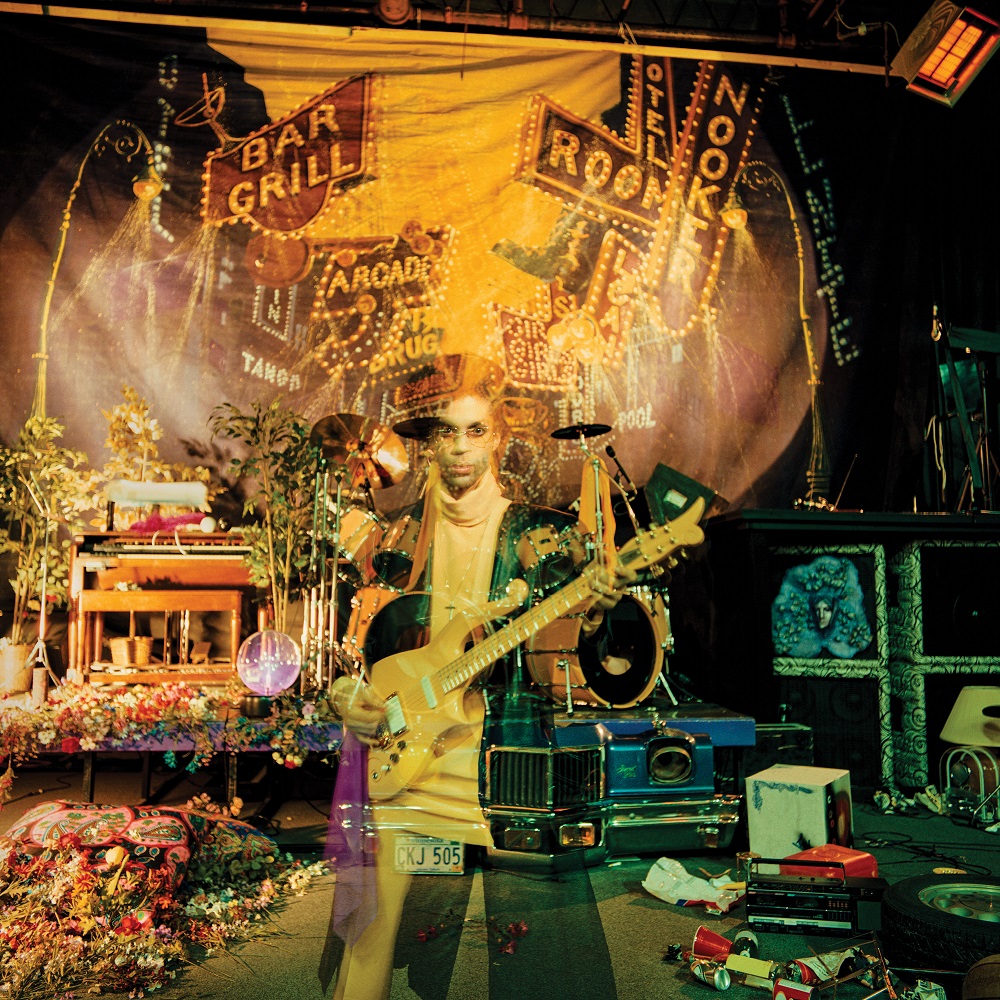

Prince. © The Prince Estate. Photo: Jeff Katz.

Okay, this is Prince, and for sure there are gems scattered across this set’s three discs of unreleased studio material (named the Vault Discs after a former bank vault under the Paisley Park recording studio complex in Minneapolis where his master tapes used to be archived). Layering multi-tracked, multi-octave vocals—a twittering throng of Prince harmonizing with himself—over a stark drum-machine pattern, “Big Tall Wall (Version 2)” is the mystifyingly never-before-released standout of the whole package. Another delight is the reggae-meets-jazzrock lurch of “There’s Something I Like About Being Your Fool,” originally written in 1981, then reworked some years later and offered to Bonnie Raitt, for whom it wasn’t a good fit. There are entertaining curios like “Cosmic Day,” featuring Prince’s vocally sped-up female alter-ego Camille, better known from the original Sign’s gorgeous “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” but here sounding like the plastic-fantastic Dale Bozzio of the Los Angeles New Wave band Missing Persons. Prince nerds will enjoy the extremely early version of “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man” recorded at the height of New Wave in 1979, which sounds as choppy and spare as “My Sharona” by skinny-tie horrors the Knack. And it’s endearing to hear Prince’s speaking voice at the start of “Power Fantastic” telling his musicians to “just trip, there are no mistakes this time, this is the fun track,” even though the outcome was probably more fun for them to play than for us to hear.

Elsewhere, though, Prince’s compulsive creativity and workaholic mania generates redundancy: lesser iterations within his many modes. Probably the least of Prince is a fallback style of sweaty git-down funk that pumped up the crowd in the live concert situation but gets wearing at home. Sometimes with the hitherto unreleased material, it’s erratic and bathetic lyrics that deflate the proceedings: the description of an attractive young woman in “Blanche” as “such a sexy wench,” the strained courtroom for love-crimes scenario of “Witness 4 the Prosecution,” the unfurling in “Rebirth of the Flesh” of the concept “a new boogie cool,” which has a tinge of English as Second Language.

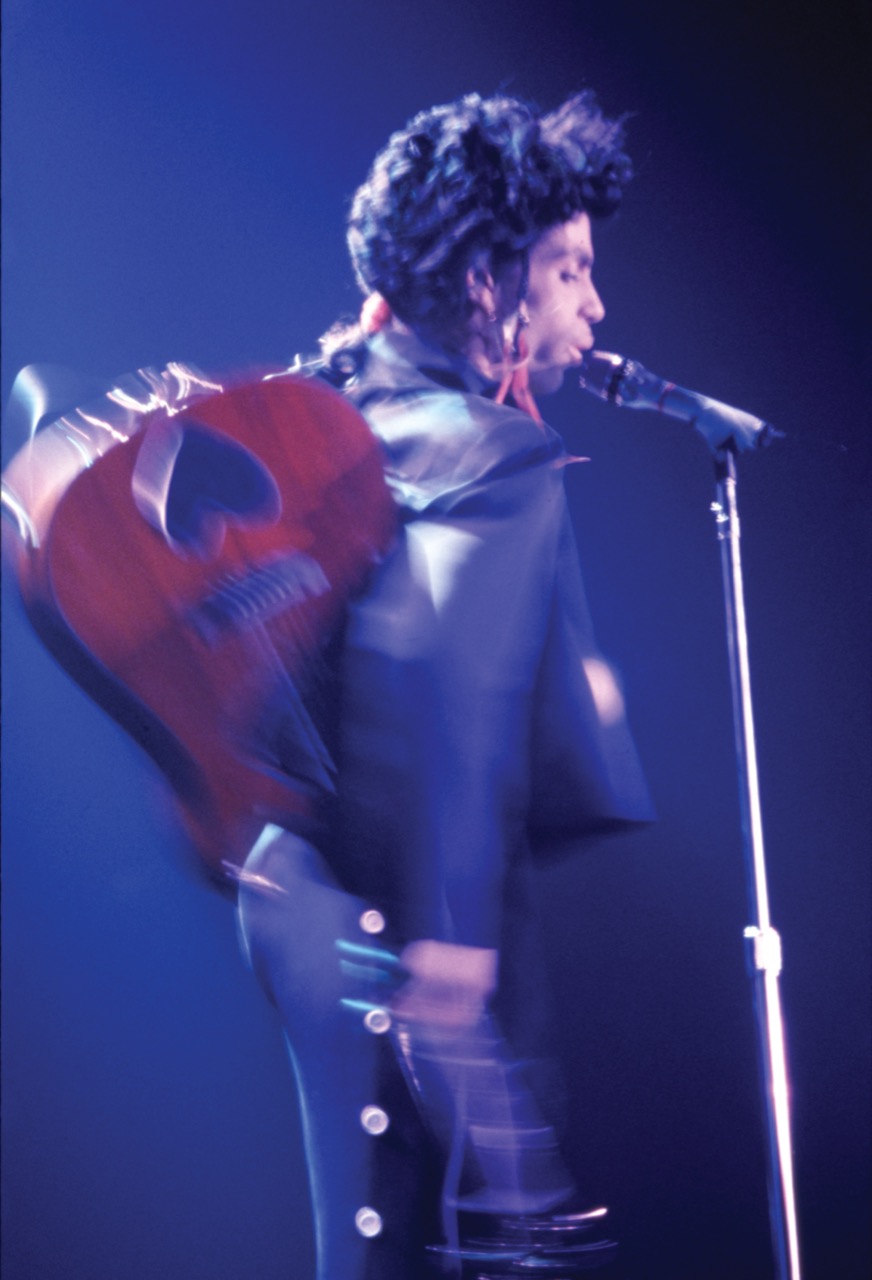

Prince. © The Prince Estate. Photo: Jeff Katz.

But even when the groove feels familiar and the writing clumsy, there’s usually some element in each track to remind you of Prince’s greatness. More often than not, it’s Prince’s way with the Linn drum machine. His off-kilter patterns and texturally “wide” drum sounds are as distinct and instantly recognizable as his voice: a testament to how genius can humanly animate and personalize technology in a way that overrides its tendency to standardize.

Digital technology would ultimate overtake Prince, though: he loved the Linn and made it swing, but he never really found a place in his music for the sequencer or sampler (the Fairlight features often on Sign, but Prince used the preset sounds already inside the machine rather than looping and collaging from other records). Before long, hip-hop, house, and the harder-edged R & B of the nineties left him behind. During that decade, Prince steadily became a kind of living museum of funk. In truth, he’d always been something of a historian, a postmodern synthesist weaving together licks and tropes from the Black pantheon (most prominently Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and George Clinton, but many others too). In a way, Prince and the Revolution was a conscious reenactment of Sly and the Family Stone: the multiracial, mixed-gender band, the sound at the intersection of soul and rock, partying as a kind of politics.

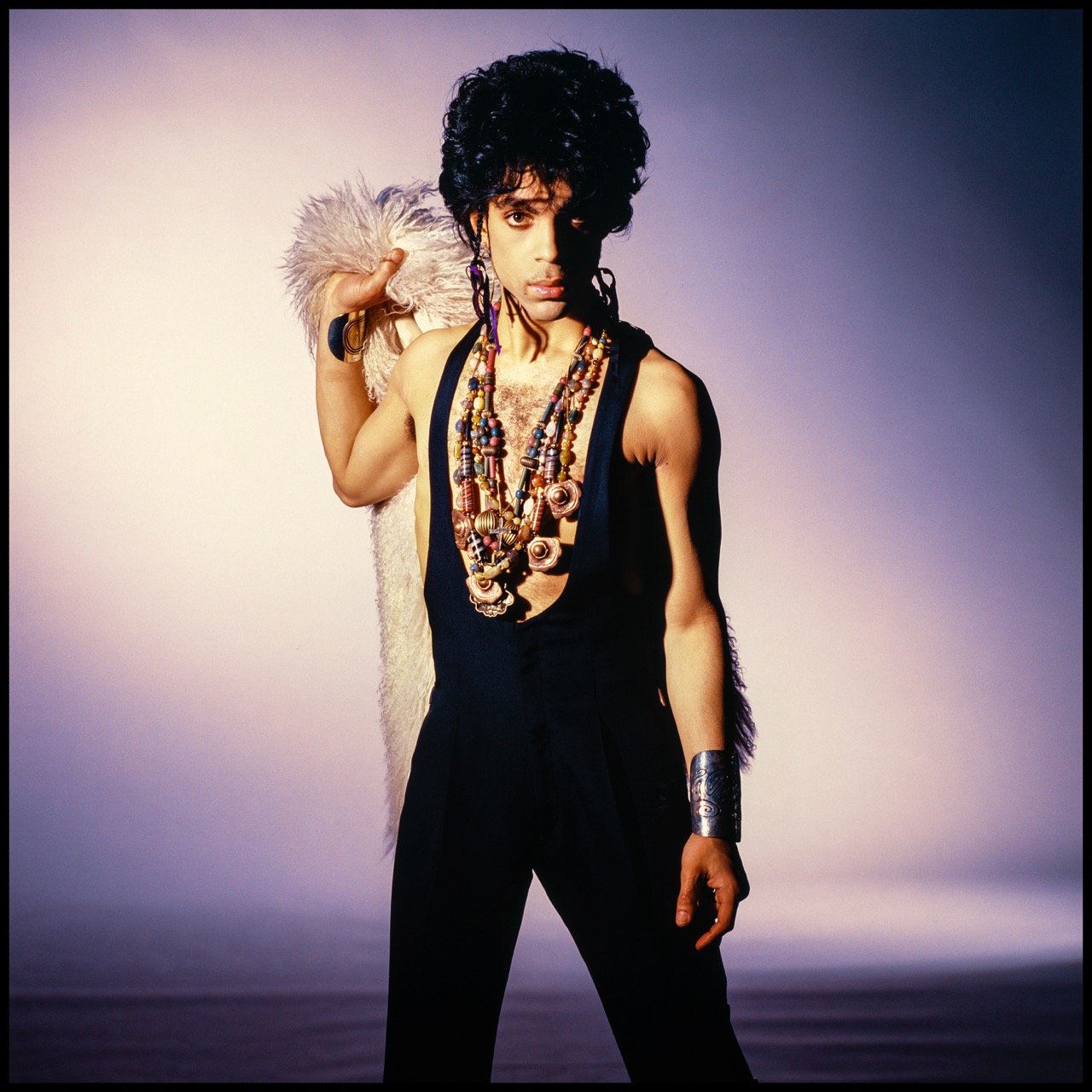

Prince. © The Prince Estate. Photo: Jeff Katz.

Where Sly’s thang was grounded in the struggles and joys of everyday people, Prince’s own vision grew increasingly mystic. From 1981’s Controversy onward, a rather wooly personal creed of spiritualized sexuality gradually emerged: Christianity without the guilt and the puritan pleasure-fear. On Sign O’ the Times, this liberation theology took on a political edge. A panoramic lamentation encompassing crack gangs, AIDs, the Challenger explosion, and other things Prince saw on the TV news, the bluesy funk of the opening title track was hailed as a “What’s Goin’ On” for the eighties. Similarly scanning a social landscape of mothers struggling to feed their children, “The Cross” is a hard-rock hymn that resembles that other defining Minneapolis sound of the eighties, the soaringly melodic, blisteringly fierce, achingly yearning punk of Hüsker Dü. Prince imagines a savior who’ll take care of “all of our problems.” Prince’s own messianic tendencies, glimpsed in the Purple Rain song “I Would Die 4 U,” blossom with the positivity credo of his next album, Lovesexy, the formation of another backing band called the New Power Generation, and the replacement of his name with the Love Symbol, an unpronounceable glyph that androgynously fused the male and female symbols, and obliged deejays and journalists to identify him as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince.

The phrase “sign of the times” comes from the New Testament and refers to the tribulations and desolations that prefigure the apocalypse and Christ’s return. This second coming of Prince’s greatest album is the immaculate execution of a flawed conception: the belief that you can never have too much of a good thing. One of the reasons Prince renamed himself was to aggravate Warner Bros. to the point where they would agree to renegotiate his contract—the source of the conflict being that he wanted to release two albums each year whereas they worried about flooding the market. Perhaps in that sense, for better or worse, this Super Deluxe Edition does reflect truly the uncontrollable copiousness of Prince.

Simon Reynolds is the author of eight books about pop culture, including Retromania, the postpunk chronicle Rip It Up and Start Again, the techno history Energy Flash, and Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the 21st Century. Born in London, currently resident in Los Angeles, he is a contributor to publications including The Guardian, Pitchfork, and The Wire, and operates a number of blogs centered around the hub Blissblog.