Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

From the Unabomber to contaminated art: a series surveys the work of the German filmmaker.

Lutz Dammbeck, Live! © DEFA-Stiftung, Helmut Krahnert.

“Lutz Dammbeck,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, September 16–24, 2019

• • •

Not many people have heard of Lutz Dammbeck, much less seen his films. That’s true of many post-1960s German directors of essay films and experimental nonfiction. Jürgen Böttcher, Hellmuth Costard, Hartmut Bitomsky: all are giants little known—if at all—in the Anglo-speaking world.

Dammbeck was born in 1948 in Leipzig in the former East Germany and moved to Hamburg in the West in 1986. He started out in painting and graphic design, sometimes operating in parallel as an animator, and began making features—initially for television, later for the big screen—only in the late 1980s. Without exception, these are quietly sensational works: addressing the collision (and collusion) of art and politics; drawing on little-known histories of psychology, social science, and multimedia technology; steeped in a melancholia that will be familiar to admirers of Eastern Bloc art.

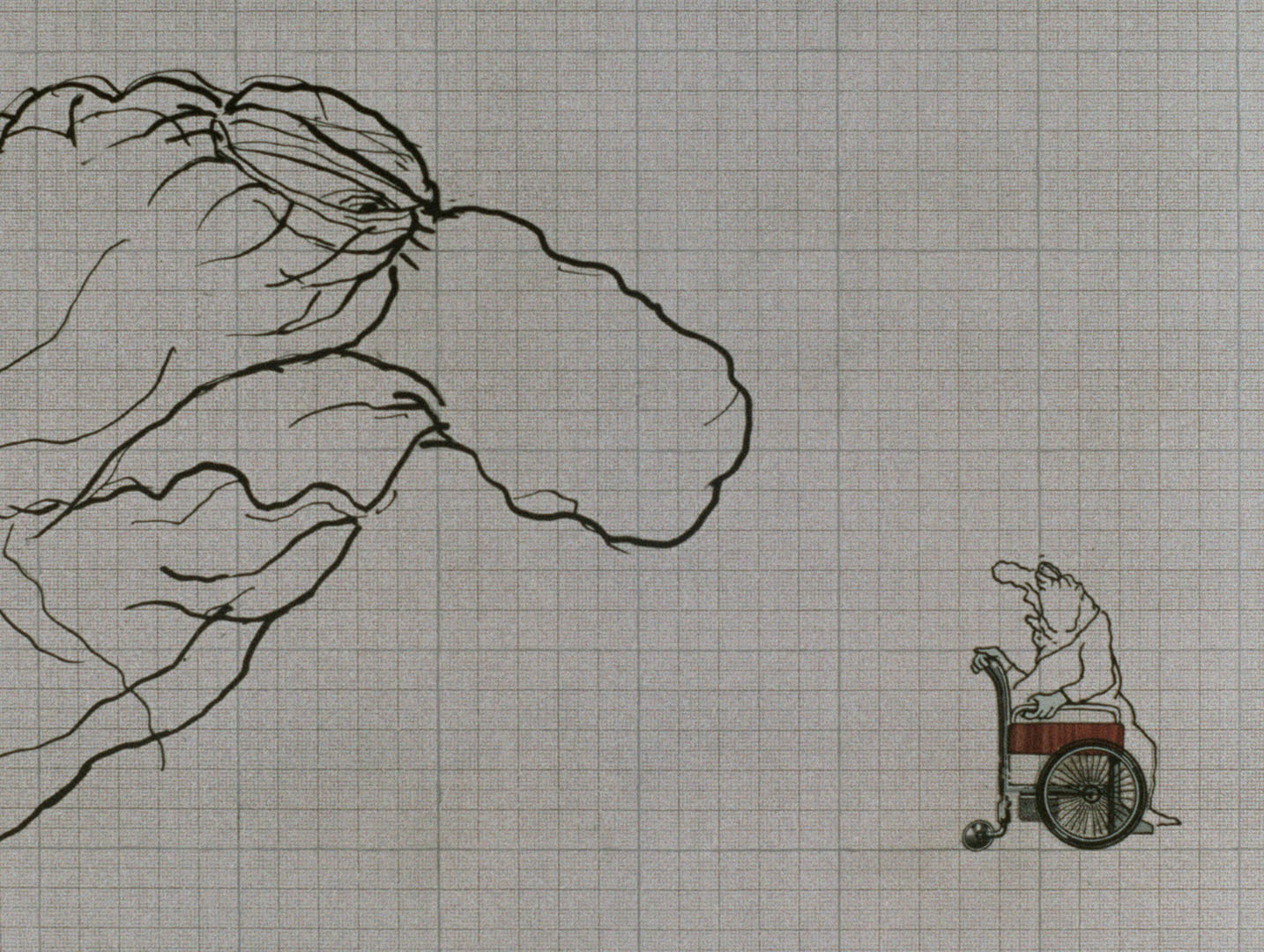

Metamorphoses 1. © Lutz Dammbeck.

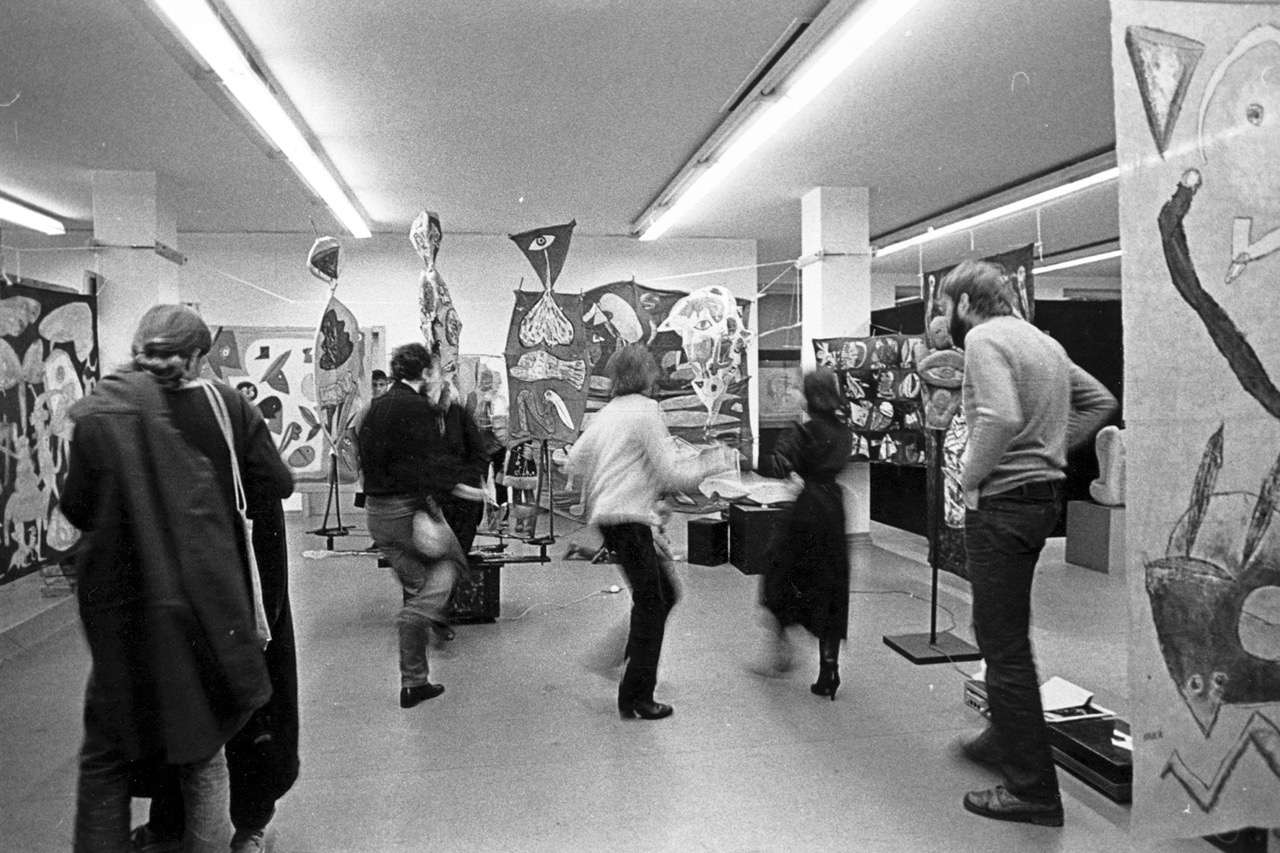

An in-depth retrospective of Dammbeck’s work at Anthology Film Archives includes his sly, sonically ambiguous animations, such as Metamorphoses 1 (1978), which was the first experimental film to be publicly screened in the GDR. It also offers the exciting if bittersweet First Leipzig Autumn Salon (1984–2008), black-and-white documentation (made with a stolen camera) of a controversial exhibition he and artist friends staged semi-illegally in Leipzig.

First Leipzig Autumn Salon. © Lutz Dammbeck.

One of Dammbeck’s central obsessions is contaminated art: works that are regarded as ideologically suspect or on the wrong side of history. A case in point is Time of the Gods (1992), which mulls over the strange career of Arno Breker (1900–91), a German architect and sculptor who hung out with the Parisian avant-garde in the 1920s. A decade later the Nazis accused him of being degenerate, but Breker found favor with Hitler, who called him his Phidias—after the Greek sculptor whose statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Time of the Gods. © Lutz Dammbeck.

Dammbeck isn’t interested in prosecution. His portrait is full of crinkles and complications. He airs diverging opinions on the sculptor’s aesthetics—those of collectors, gay bibliophiles, the Soviet soldiers who were ordered to take Breker’s statues to junkyards. He meets with Jean Marais, the anti-fascist French actor who protected Breker from arrest. Most palpable in the film are the ghosts of German reunification. Younger artists ponder the difficulty of executing models, and claim that artists as a breed are no longer idealized: “We muddle around, and Breker’s stature, it’s like a dream.”

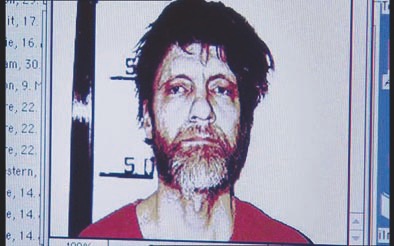

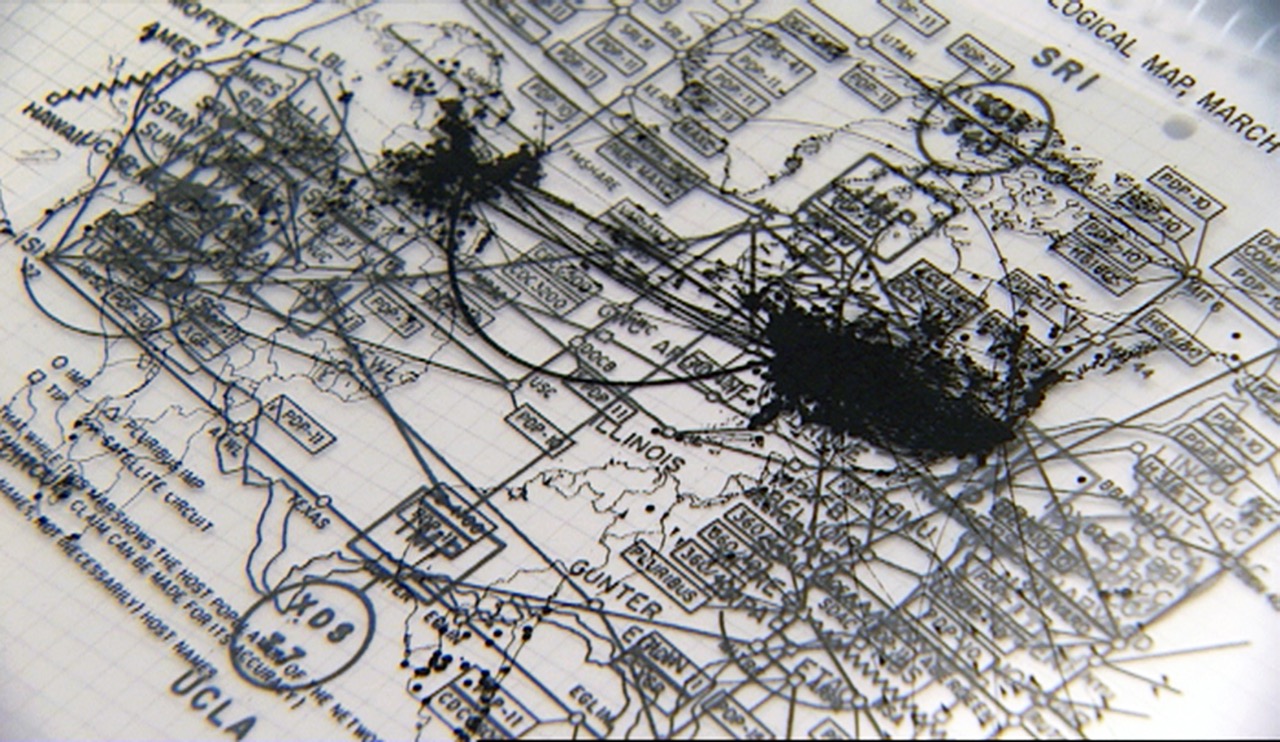

The Net. © Lutz Dammbeck.

Dammbeck’s best-known film in the States is The Net (2003). It’s a roaming and rather prescient exploration of how Ted Kaczynski, a math prodigy with an IQ of 167, turned into “the Unabomber,” the technophobic terrorist who killed three people and injured twenty-three others between 1978 and 1995. Errol Morris might have fashioned a stylishly lurid “mind of a murderer” thriller from this material; Dammbeck is more curious about the cultural and political contexts that led to Kaczynski’s ballistic critique of modern society.

The film begins with a question: Why, in the 1960s and early 1970s, were so many experimental artists, among them Nam June Paik, John Cage, and Joseph Beuys, passionate about the same topics—multimedia, cybernetics, virtuality—as computer scientists and university researchers were? Other queries soon follow: Why were so many of the leading intellectuals of the day drawn to the idea of human beings as “information processing systems”? What role did LSD play? And how did such utopian accelerationism curdle into the dystopian visions of someone like Kaczynski?

The Net. © Lutz Dammbeck.

Dammbeck structures his film as a travelogue, visiting the likes of investment-banker-turned-experimental-cinema-promoter John Brockman (and, we’ve learned lately, friend of Jeffrey Epstein), who became a hugely successful agent packaging physicists and chemists as rock stars. Road miles are racked up. Dammbeck’s notebooks get more congested. He exchanges letters (in German) with Kaczynski. A picture, sometimes blurry, emerges: of the counterculture’s fondness for game playing, of revolutionary discourse and reality engineering being entirely compatible with—rather than a threat to—late capitalism. Is this true? I certainly agree. In any case, the film is prefaced by a quote from the Austrian mathematician and philosopher Kurt Gödel: “The truth is superior to provability.”

Overgames. © Lutz Dammbeck.

Even more ambitious is Overgames (2015), a riveting 164-minute essay that tries to gauge the truth of a claim made on a German chat show: that the US introduced TV game shows to post–World War II Germany that were based on exercises first tested on American psychiatric inmates. The reason? To pacify and reprogram Deutschland’s legendarily violent population. It’s an incredible and seductive and preposterous assertion. To explore it, Dammbeck turns to eighteenth-century theories about freedom and childhood, delves into the semi-hidden history of the Macy conferences on cybernetics staged in New York in the late 1940s, and reanimates the still-terrifying Milgram’s Obedience and Stanford Prison Experiments.

Overgames. © Lutz Dammbeck.

Along the way he includes startling footage of a huge Nazi rally held at Madison Square Garden in 1939, whose potential impact was partly blunted by the street-fighting tactics of the Kosher Nostra. There’s a segment on renowned anthropologist Gregory Bateson’s stint as a film analyst at the Museum of Modern Art, where he studied popular German films in order to better understand that country’s pathologies. There’s also a scene outside the recording studio of The Price Is Right in which would-be contestants whoop it up (“I have two kids. A husband. I want a car. A nice car!”) and talk, not at all trivially, about what the program means to them. A companion of sorts to Neil Postman’s more polemical book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985), Overgames is also very much Adam Curtis terrain—but free of that director’s ADD editing and wayward grasp on causality.

Bruno & Bettina. © Lutz Dammbeck.

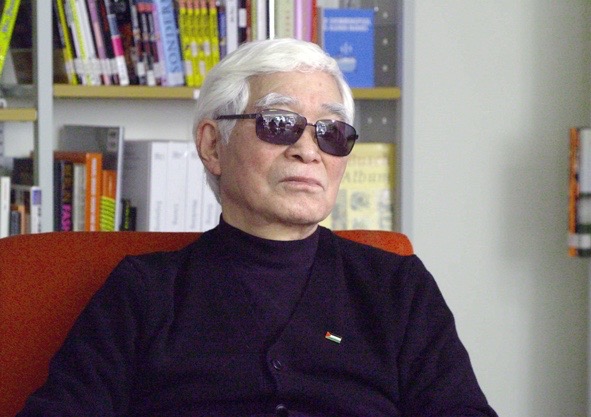

Political filmmakers are often claimed as cultural front workers whose cameras are weapons. If that’s true of anyone it’s true of Japanese refusenik Masao Adachi (born in 1939), the subject of Dammbeck’s most recent feature, Bruno & Bettina (2018). It’s formally modest—a lengthy interview interspersed with clips of rare films and archival footage of student unrest—but absolutely riveting.

Wearing shades, Adachi discusses the underground scene in ’60s Japan, the pornographic “pink” films into which he smuggled radical messages, and his eventual departure for Beirut, where he joined the Japanese Red Army’s struggle to support the Palestinian liberation movement. Bruno & Bettina ends with Dammbeck, off camera, asking a discomforted Adachi explosive questions about the relationship between the Stasi and the Japanese Red Army. Complicities and paradoxes, ideological gray areas, the ironies and intricacies of history: Dammbeck’s films illuminate—and deepen—them all.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for The Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.