David L. Ulin

David L. Ulin

In George Saunders’s follow-up to Lincoln in the Bardo, death comes for us all—with the possibility of grace.

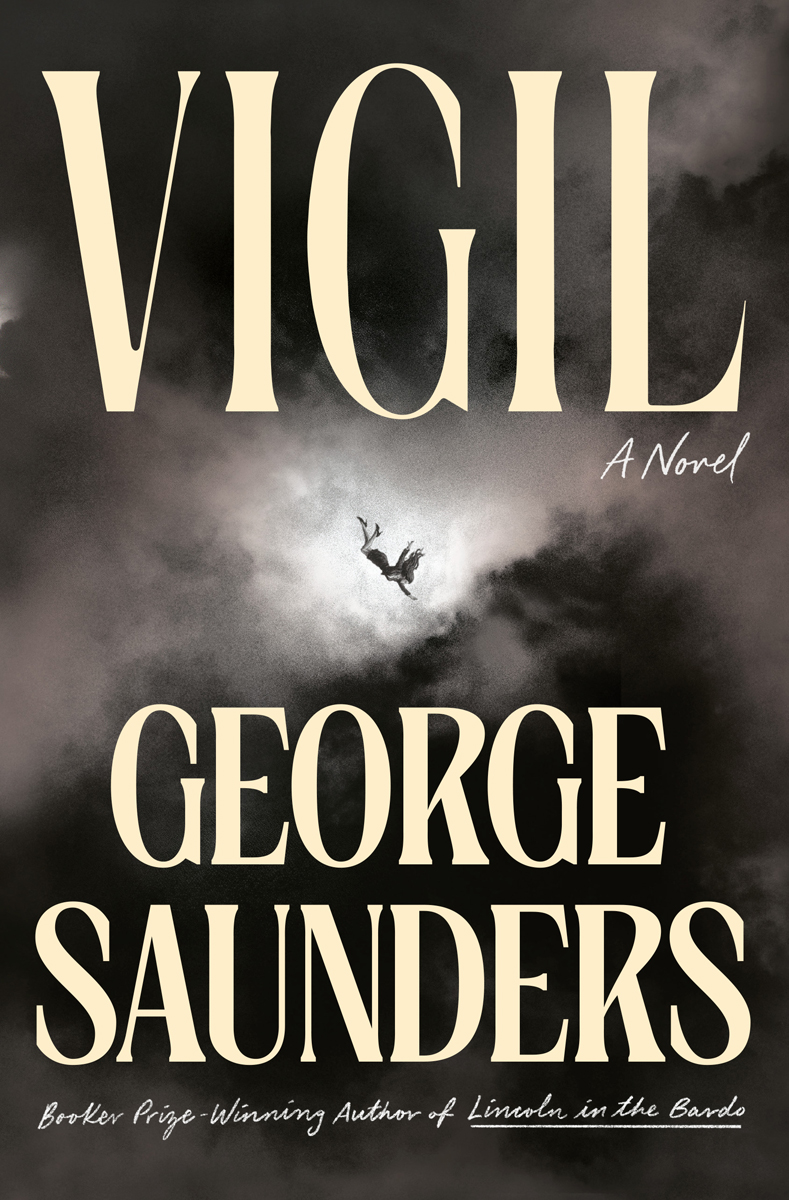

Vigil, by George Saunders,

Random House, 174 pages, $28

• • •

It’s impossible to read George Saunders’s second novel, Vigil, without thinking of his first, Lincoln in the Bardo, which won the 2017 Man Booker Prize. Narrated by a celestial agent sent back to earth to comfort a man during his final moments, Vigil—like its predecessor—takes place over the course of a single night, and if the word bardo does not appear in its pages, such a space, such a way station between living and dying, is the territory in which it unfolds. “Before me,” the narrator observes, “lay a person who had not willed himself into this world and was now being taken out of it by force.” This, of course, is true for every one of us: born, never asked (to borrow from Laurie Anderson), and condemned, as each living creature must be, to the depredations of mortality and time.

That this includes the narrator is only as it should be, for Saunders is nothing if not a humanist. Over the course of his career (which includes, among varied other publications, five groundbreaking books of short fiction), he has traced the fluid boundary between outer and inner life, excavating the divide between who we are and how we see ourselves. The title effort of his 2013 collection Tenth of December turns on the instant when a dying man, intent on suicide, must face his ethical responsibility after witnessing a boy fall through the frozen surface of a pond. The 2019 story “Elliott Spencer” revolves around an elderly man, exploited by what appears to be a caregiver into behaving as a political counterprotester, who finds salvation—or, at least, the possibility of some elusive reclamation—in the small bits and pieces he recalls of his past. This is writing that exists in a moral universe, although it is not in any way easy or safe. “Then suddenly something softened in me, maybe at the sight of Ma so weak,” the narrator of “Home” (2011) informs us, explaining the decision not to harm his family, “and I dropped my head and waded all docile into that crowd of know-nothings, thinking, O.K., O.K., you sent me, now bring me back. Find some way to bring me back, you fuckers, or you are the sorriest bunch of bastards the world has ever known.” What Saunders is describing is the psychic duty we bear toward one another, the difficult comfort of keeping our hearts open: of being present and responsive, as it were.

Difficult comfort sits at the center of Vigil, also; it’s the engine that drives the book. The dying man is K. J. Boone, a Texas oil baron whose manipulation of false or skewed science during the 1990s has helped to precipitate global climate collapse. “Get lost,” he tells the narrator on their first encounter. “I don’t want you.” The response, she suggests, is “unusual . . . to say the least.” That’s not because people embrace fate in these moments but rather the opposite: the hope that there might be “guides, guardian angels, spooks, phantoms, who late in the game, showed up to help a guy along.” Still, if such figures do appear in the cosmology of the novel, it has nothing to do with the way one has lived. Death is inevitable but also arbitrary.

The narrator represents a case in point. Born Jill Blaine, she was only twenty-two when she was killed by a car bomb intended for her husband, an assistant deputy. Early in Vigil, she describes her cadaver, buried in her hometown of Stanley, Indiana: “a desiccated brownish-green figure of medium height (length), cleaved in half at approximately the hip-line, left arm disconnected at the shoulder, a fuzz-beard of mold on what was left of its cheekbones.” The clinical nature of the image is entirely the point. If the narrator was once Jill, she is Jill no longer. “No,” she avers, “this, this now, was me: vast, unlimited in the range and delicacy of my voice, unrestrained in love, rapid in apprehension, skillful in motion, capable, equally, of traversing, within a few seconds’ time, a mile or ten thousand miles.”

As if to emphasize the transience of her former state, Saunders sets off a number of common nouns or names in quotation marks: “school desk,” “compass,” “Sears,” “swing set,” “Jill Blaine.” The implication is that her own earthly identity is as much a part of the world of illusion, of surface and deception, as any physical object or location. The corollary is that the same applies to Boone.

“Comfort,” she insists, “for all else is futility.”

The irony is that even now, the narrator remains susceptible to the pull of everything she’s lost. “Oh, I felt just sick,” she laments. “I did not want to be THIS THING anymore, this stiff elevated THING, but wanted, instead, to be me, sweet ME again, all the way, and for this whole awful dream . . . to be DONE, so I could be . . . back in that beautiful living body I knew and loved so well.”

And yet, if Vigil has anything to tell us, it’s that there is no returning, neither to the past nor anywhere else. There is only acceptance, which extends to protagonist and antagonist alike. For the narrator, that means the accountability the universe has bestowed upon her, the requirement that she serve not only as facilitator but also as a witness of sorts. For Boone, accountability takes a different shape: neither his wealth nor his influence, the homes he owns nor the power he has held, can alter the final disposition of his soul. Here, we see the toughness of Saunders’s vision; “It was hard, this life,” the narrator admits. All the same, in that flinty rigor, we discover forgiveness, generosity, even grace. Like Jill, after all, Boone is only and ever who he is. His life could not have gone another way. “Who else could you have been but exactly who you are?” the narrator asks, and in that question, the mercy of the cosmos is revealed. It’s not that we are without agency, but that agency is a complex business, in which, as Saunders reminds us, “if your worth depends on your glories, it must also depend on your sins.” The balance upon which existence relies, in other words. World—or, perhaps I should say, bardo—without end.

David L. Ulin is the author of Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, which was shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times.