4 Columns

4 Columns

For our third summer missive, reviews that center on place and

feelings of home.

Stephen Shore, U.S. 97, South of Klamath Falls, Oregon, July 21, 1973, 1973. Chromogenic color print, printed 2002, 17 ¾ × 21 15⁄16 inches. © 2017 Stephen Shore.

How does place hold history? Does a land rebellion that occurred in the nineteenth century still last on that very land into the present, permanently etched there—through memory, through memorial, through blood in the soil? Does a childhood home still contain the ache of imagined possibility, long after the child has grown up and left—can place hold a feeling, forever?

If the answer to those question is yes, then maybe place makes time become three-dimensional, past and present and future collapsing into a physical point, all at once. And trying to write these functions of place can break writing (its conventions, its teleologies, its neat plots) altogether, creating space for new forms and ways of writing, reading, thinking, being.

On June 26, 2025, 4Columns hosted the event Place Is the Space at the Francis Kite Club in downtown Manhattan to mark the publication of contributor Jennifer Kabat’s new book Nightshining (Milkweed Editions), in which Kabat explores these questions of place- and space-making. It was a tender, intimate, and searchingly personal evening, in which a stellar lineup of 4Columns contributors (in reading order: Chris Kraus, Sukhdev Sandhu, Lynne Tillman, Sowon Kwon, and Paul Chan) reflected on a place that has held and still holds them, even if they are (or it is) no longer there. A rapt audience took in stories of rural America, a lost library in England, summers on the Atlantic coast in Long Island, a sculpture at the UN and landscapes of paranoia, and a restaurant that evokes a childhood spent in hospitals.

In this week’s roundup of picks from our archive, we feature a review by each of these speakers that similarly travel through time and space.

• • •

CHRIS KRAUS ON SOMEBODY WITH A LITTLE HAMMER

America: a place founded on bloodshed and horror, surviving on its own myth of exceptionalism, but also filled with dreams and hopes—a complicated land, indeed. In her review of Mary Gaitskill’s first essay collection, Somebody with a Little Hammer (published by Pantheon in the spring of 2017, early in Trump’s first tenure), Chris Kraus details how the fiction writer’s essays unspool notions of American history, culture, and class with sensitive nuance. For instance, “ ‘Americans,’ [Gaitskill] writes in ‘Victims and Losers: A Love Story,’ are ‘terrified of being victims, ever, in any way,’ ” Kraus recounts. “As she explains, ‘I think it is the reason every boob with a hangnail has been clogging the courts and haunting talk shows . . . telling his/her “story” and trying to get redress. Whatever the suffering is, it’s not to be endured, for God’s sake, not felt and never, ever, accepted. It’s to be triumphed over.’ ”

• • •

SUKHDEV SANDHU ON THE WICKEDEST

South London: a place of “hostile architecture”—in the words of Sukhdev Sandhu in his review of Caleb Femi’s poetry collection The Wickedest, out from MCD in early 2025—a slice of modern Britain that gets forgotten or is rarely glanced at, where colonial histories still strangle the present but where young people seek liberation through music and movement. The Wickedest, like Femi’s first collection, Poor, “is set in South London—at a secret location—and shares its name with what Femi claims is the longest-running house party in that neck of the woods.”

And, house parties: places of freedom, chaos, sweat, illicit joy. “Black British history has always been forged partly at night,” Sandhu writes. “In the decades after World War Two, it was a tradition for intrepid reporters to try and get access to the colony within—inner-city shebeens and basement blues parties whose weed-fug and jump-up noise they’d chronicle for their titillated readers. These dances, often held in terraced homes or small community halls because the landlords of more traditional venues didn’t want immigrant punters, had the heightened intensity of a survival shelter or an insurgents’ safe house.”

• • •

LYNNE TILLMAN ON STEPHEN SHORE

Stephen Shore, Uman, Cherkaska Province, Ukraine, July 22, 2012, 2012. Chromogenic color print, printed 2017, 16 × 20 inches. © 2017 Stephen Shore. Image courtesy 303 Gallery.

Ukraine: a place that often gets left; a nostalgic homeland, for diasporic communities in the US, that exists in family stories and hand-me-down memories. In her review of a 2018 MoMA retrospective of photographer Stephen Shore, Lynne Tillman talks about Shore’s images of American roads and highways, of New York City and Andy Warhol’s Factory, the photos for which he is perhaps best known—but she also delves into a newer body of work centering on the lived reality of Ukraine, four years after the Russian invasion of Crimea, four years before the current horrific war. “In [this] series, also published as the book Survivors in Ukraine, Shore’s experiment was to focus on the human body,” Tillman explains. “His grandfather had emigrated from Ukraine to New York in the late nineteenth century. While that might seem a reason for why the photographs look quite different from his other bodies of work, that is not an explanation for how he achieves or executes that difference; execution is different from intention. In this series, the colors are soft, the picture planes seem fuller as if every centimeter is covered, the pictures have a supple quality. Shore shoots hands, and faces, close up. Books covered with dust, close up. The angles or geometry of spaces are less present. Maybe for these reasons an intimacy pervades the work. I can, as a writer, suggest what I see and why, but how that is achieved by Stephen Shore remains a mystery to me.”

• • •

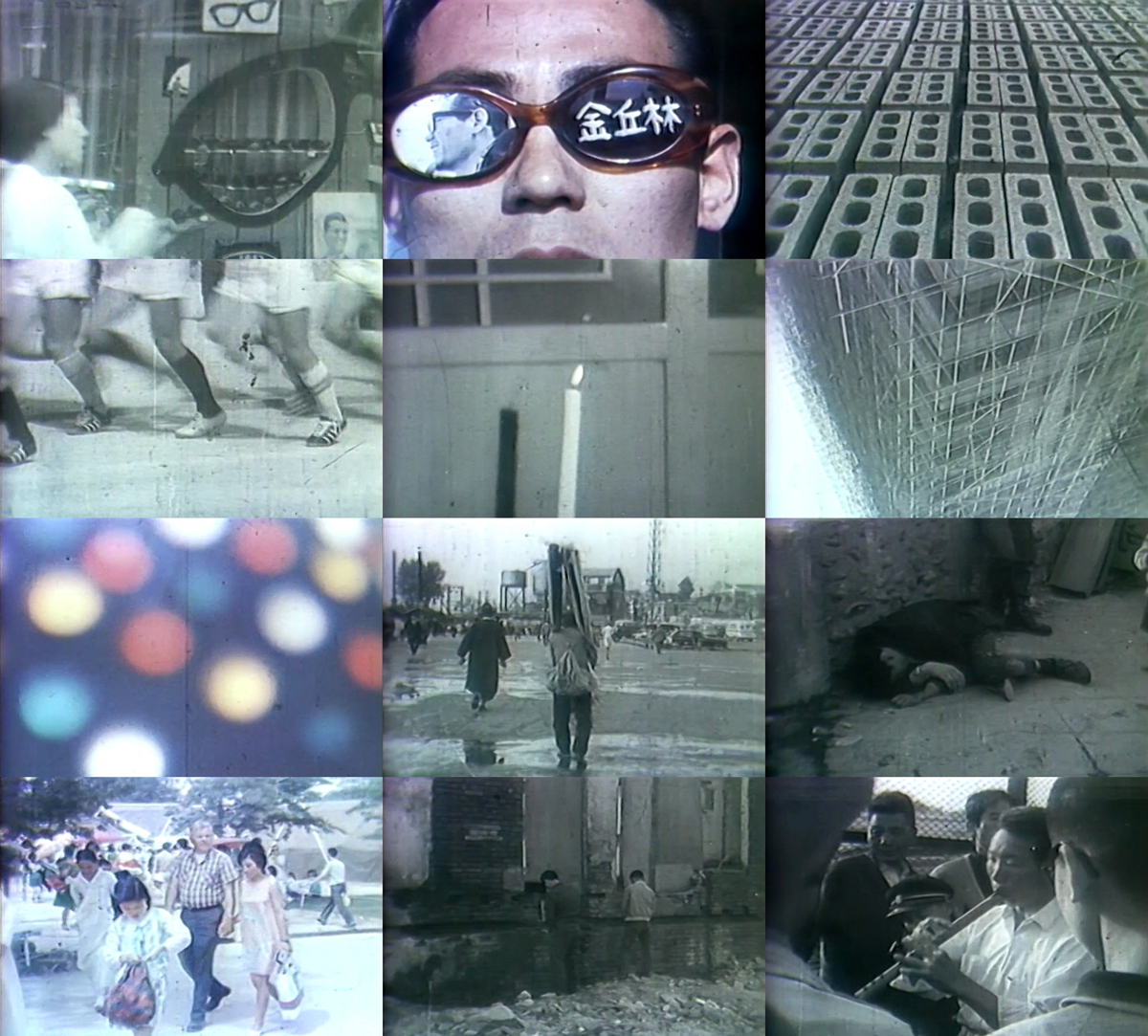

Kim Kulim, The Meaning of 1/24 Second, 1969 (still). Color 16mm film, silent, 9 minutes 14 seconds. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. © Kim Kulim.

Korea: a place marked by world wars and internal division, restless and relentless modernism and persisting folk culture, and, in the visual arts, its own evolution of the avant-garde, as Sowon Kwon writes in her review of the 2023 Guggenheim exhibition Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s. The show featured “eighty-plus works categorized as 실험미술, silheom misul—a term conferred in the early 2000s by art historian Gim Mi-gyeong—” including experimental films tracking urban anomie in Seoul, happenings and actions in city streets, midcentury paintings recalling preindustrial Korean households, collages resisting President Park Chung Hee’s brutally authoritarian administration. It was an important show—but was it successful? “The great range of practices was incredibly heartening to see,” Kwon asserts, “and yet I was left with the overall impression of a pervasive, almost sanitized elegance. In the assertion of a ‘movement’ called Experimental Art, just now being consolidated (in the guise of being retrieved) as the Korean ‘avant-garde,’ to what extent are artworks to function as ambience, and/or just so much evidentiary fodder? I have come to understand this exhibition as being as much, if not more, about art history and the discipline’s propensity for constructing neat canonizing narratives as about prioritizing artistic choices and material exploration pursued by makers.”

• • •

PAUL CHAN’S “LETTER TO YOUNG ARTISTS DURING A GLOBAL PANDEMIC”

Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, 2007 (Gentilly performance). Image courtesy Paul Chan.

Home: a place that can be hard to define, which may exist only in the mind, a place in which one can get stuck and long to leave or to which one can never return. In a special fifth column published in 2020, during the early months of COVID, Paul Chan writes that “there are many different ways of thinking about what it means to be home. Experiences that make the concept of home meaningful are as fluid and varied as our sexual identities. . . . [but] a dehumanizing notion of home is being promoted by the most barbaric voices in American life. ‘We must go back to the way things were as soon as possible,’ these voices declare. ‘The economy must reopen immediately. Businesses must business again. Workers must work again.’

Get sick if you have to. Drink bleach to cope. The meaning of home here speaks to the demand that we must return to how they were most at home with us—as the help, so to speak—for the house they think they rightfully own.

Is it worth returning to the way things were? Is there a direction home that doesn’t point backward? Does the concept and experience of art play a role in any of this? These are the questions I want to consider with you.”

• • •

JENNIFER KABAT ON A LINE IN THE WORLD

Home, again: a place that can be sensed; that exists consciously and cognitively as well as in the baser, ancient parts of our minds; that holds history, that persists no matter how far we travel. These notions of home were explored by Jennifer Kabat in her 2022 review of Danish author Dorthe Nors’s essay collection A Line in the World (Graywolf Press). “The book and its themes make me think of a tiny saffron salamander, the red eft, that lives on my land, and that creature’s deep sense of place,” Kabat writes. “The other side of being lost isn’t just knowing where you’re going, but rather knowing somewhere that’s held inside yourself. This eft, the juvenile form of the Eastern newt, has an ineffable, improbable sense of home. It wanders miles and miles into damp forests only to return one rainy spring night to its home pond. The eft contains, scientists speculate, a small bit of iron, like an inner compass. Nors writes of such peregrinations, like the migration routes of birds. They too, it turns out, have an inner compass, and this subliminal sense of home is Nors’s subject.”