4 Columns

4 Columns

Three movies in which moviemaking itself plays a starring role.

Margot Robbie plays Nellie LaRoy in Babylon. Courtesy Paramount Pictures. Photo: Scott Garfield.

The youngest art form, cinema may also be the most self-referential. In fact, one of the most beloved films of all time, among both critics and audiences, is a meta-movie: Singin’ in the Rain (1952), Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s vivacious musical about cinema’s shift from silence to sound. Seventy years later, a much lesser feature, one that heavily quotes from that midcentury classic, would frantically depict the transition to talkies. In her pan of Damien Chazelle’s Babylon (2022), which traces Hollywood from 1926 to 1932, film editor Melissa Anderson called it “clamorous and benumbing . . . a three-hour cartoon with expletives, dildos, and excreta.” Its nods and winks quickly wear thin: “Much of Babylon plays like a parlor game designed to flatter the TCM devotee: guessing who’s who or which movie or scandal is being referenced affords the same empty pleasure as figuring out which Minnelli, Demy, or Donen film Chazelle was saluting in La La Land, his wan 2016 musical,” Anderson writes.

Gaspard Ulliel as Igor, Adèle Exarchopoulos as Margot, and Sandra Hüller as Mika in Sibyl. Courtesy Music Box Films.

Other directors display a more confident hand while in meta-mode. Justine Triet’s sinuous Sibyl (2019) focuses on the chaos that ensues when the psychotherapist and novelist of the title (played by Virginie Efira) is summoned by one of her distraught clients, an actress named Margot (Adèle Exarchopoulos), to the volatile set—Margot is having an affair with her costar, who’s married to the director—of her latest film, Never Talk to Strangers, shooting in Stromboli. “Scenes from that movie-within-a-movie are pleasingly difficult to distinguish from Sibyl’s own unfolding plot,” Anderson notes. Additionally, “nested within the Stromboli-set scenes are clever [hints] to other films—works refracted by Triet’s nimble movie. The volcanic Italian island was also the location of the first collaboration between Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman; while making Stromboli (1950), the director and actress scandalously began an affair that ended both their marriages. Exarchopoulos, who . . . impressively vacillates between wretchedness, fury, and sangfroid, is—and will probably always be—best known for Blue Is the Warmest Color (2013), the strenuous sapphic epic made even more notorious after she and costar Léa Seydoux candidly spoke about director Abdellatif Kechiche’s grueling filming methods and the overall anguish on set.”

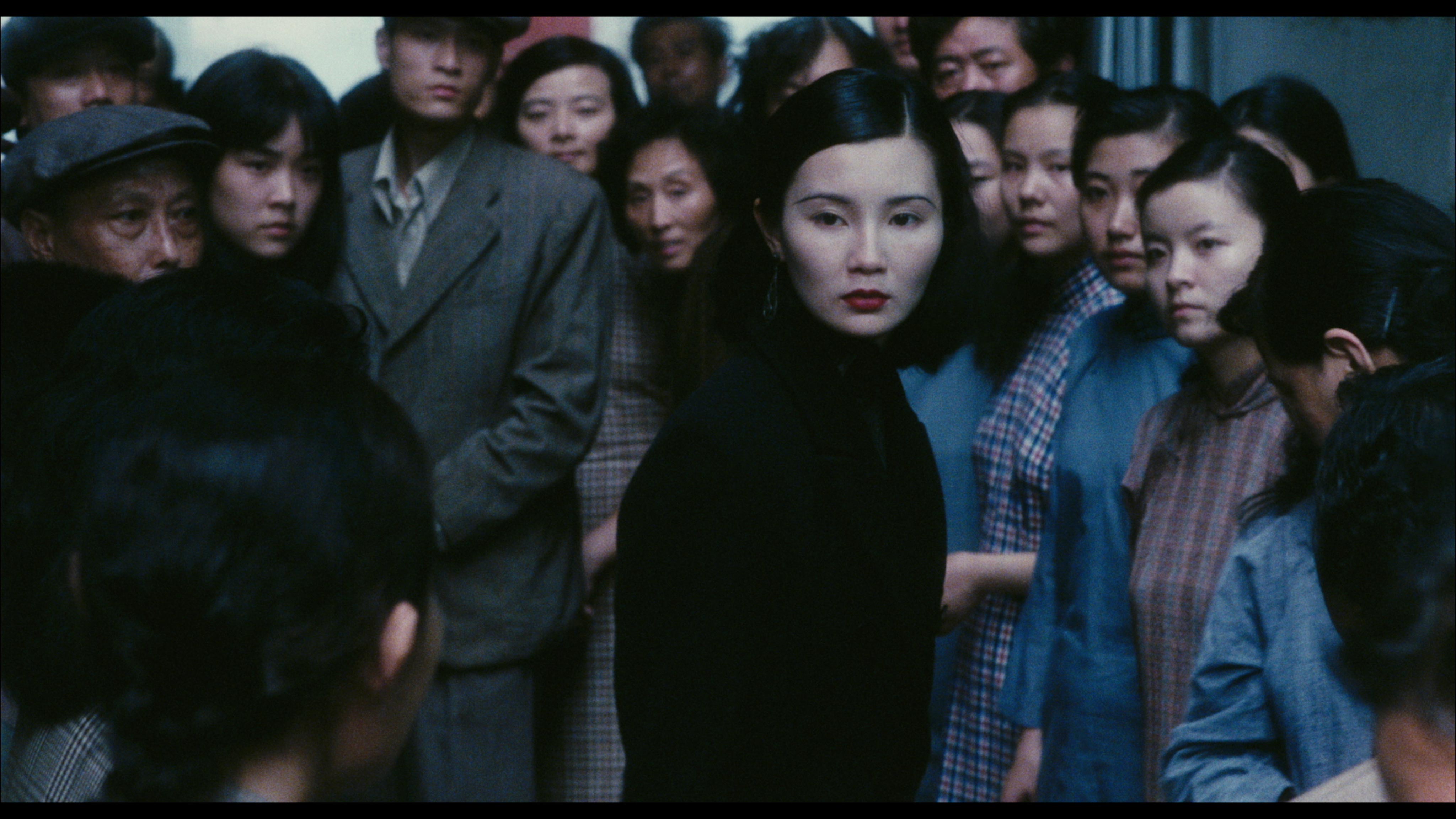

Maggie Cheung in Center Stage. Courtesy Film Movement Classics.

Perhaps the paragon of this recursive genre is Stanley Kwan’s protean biopic Center Stage (1991), about the Shanghai silent-screen divinity Ruan Lingyu, portrayed by Maggie Cheung. In this fascinating hybrid, Cheung plays at least three roles: herself, appearing intermittently in segments in which she and Kwan speak to Ruan scholars and contemporaries; Ruan, both on and off the set; and the characters the icon performed in the various films re-created in Kwan’s project. “Where most biopics hinge on moments when the private self suddenly leaks into public visibility, Center Stage avoids fabricating any scenario that might offer a convenient key to the heart of Ruan,” Andrew Chan observes in his tribute to the film. Pointing out that Center Stage’s “self-reflexive method invites viewers to consider the subtlest permutations of form and meaning, as well as the medium’s twin capacities for revelation and deception,” Chan stresses that “the film is no mere intellectual exercise.” Among the signal achievements of Kwan’s movie is how it “evokes the loneliness of the performer, who is forever caught between the emotional transparency her art demands and the privacy she requires to protect those emotions.” It’s a grand allusion.