4 Columns

4 Columns

If you don’t have anything nice to say, we say go ahead and say it anyway.

Margot Robbie as Nellie LaRoy in Babylon. Courtesy Paramount Pictures. Photo: Scott Garfield.

It’s never seemed quite so dangerous to articulate critical judgment in public.

In 2020, Jill Mapes published a decidedly positive review of Taylor Swift’s Folklore that glancingly acknowledged the Pitchfork editor’s ambivalences about the album. Within hours, Mapes’s personal details were revealed online by Swift stans furious at her less-than-perfect allegiance to their idol; death threats expeditiously followed. In February of this year, after German dance critic Wiebke Hüster slammed, in print, Marco Goecke’s latest ballet, the choreographer responded with physical assault, publicly smearing dog feces over her face. It was thus perhaps not surprising when, in March, New York Times film critic A. O. Scott announced he was leaving his role, in part due to the general readership’s rapidly worsening intolerance to differing opinions. (He, too, has felt the wrath of online swarms, for voicing his hatred of Marvel movies.)

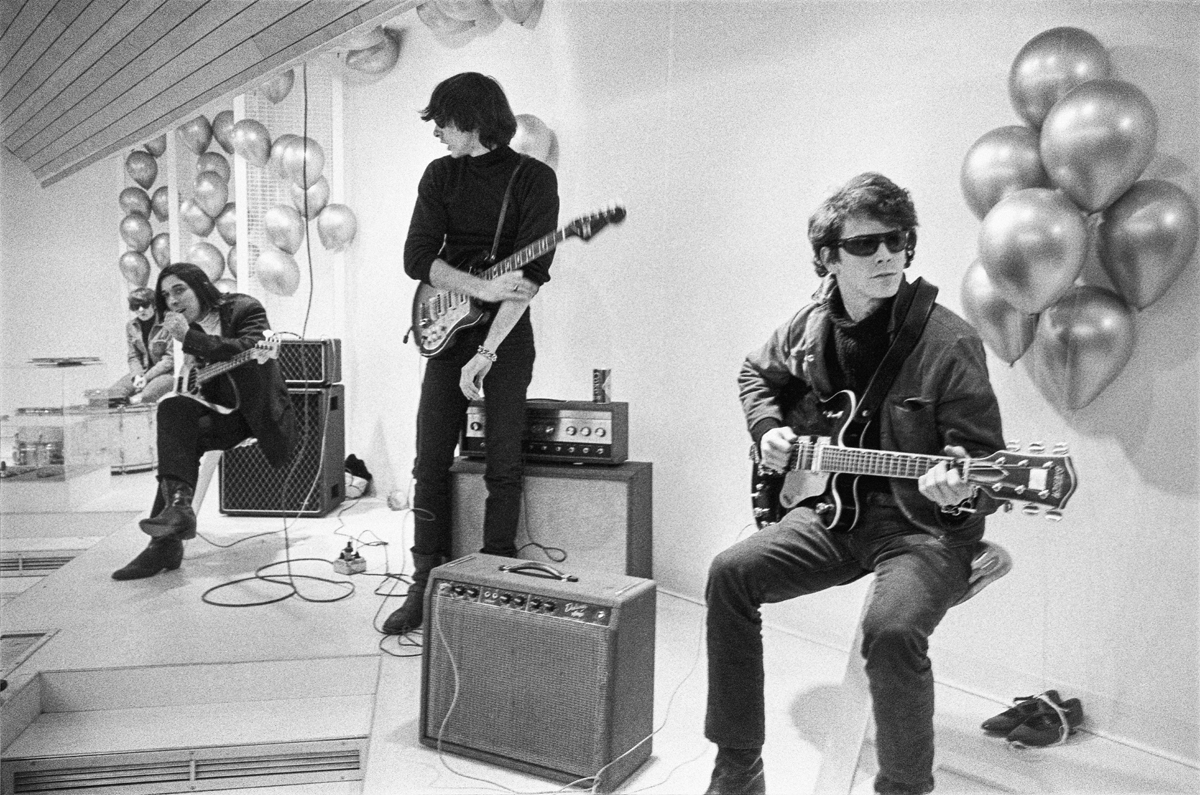

Archival split-screen frames from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

In such a climate, why would a critic risk triggering tidal waves of outrage by penning a pan? For NPR writer Ann Powers, the answer goes to the very heart of what criticism itself is for. Sharing ambivalences about, arguments with, and negative feelings toward a cultural object is a vulnerable opening up of a singular point of view that can foster empathy, she proposed in an essay for Slate on her own experience with virulent backlash from a public angered by her take on Lana Del Rey. For Powers, such acts of sharing help dissolve the fiercely guarded silos of opinion that characterize an increasingly fractured and factionalist society. Scott has similarly argued that if “fandom is about obedience and about conformity,” then criticism is about exchange and conversation, the antidote to “a very strong and visible anti-democratic or authoritarian tendency.”

4Columns shares this editorial perspective on the necessity of the bad review—to which end, we’ve published our fair share of critical “breakup notes” since our first issue appeared in the hotly divisive social and cultural context of 2016. For this week’s summer missive, as we contemplate the importance and the peril of negative criticism, we offer a reading list of some of the most powerful bad reviews in our archives, authored by critics fueled by passions both personal and political.

• • •

ARUNA D’SOUZA ON SHIRIN NESHAT

Shirin Neshat, The Fury, 2022 (still). Two-channel, HD monochrome video, 16 minutes 15 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. © Shirin Neshat.

Long critical of Shirin Neshat, Aruna D’Souza felt compelled to speak out about the artist’s recent show, The Fury, at Gladstone Gallery. D’Souza identified an insidious logic operating at the heart of the market darling’s newest works: “Neshat, not satisfied with her usual schtick of stereotyping Iranian men and women, uses Black people and other people of color to act out the violence felt by her abused main character. Her fury, the aftereffect of her trauma, is expressed through these instrumentalized bodies. It is a perverse message.”

• • •

JENNIFER KRASINSKI ON DANH VO

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017.

A robust scaffolding of critical hype has been built around Danh Vo, who’s “billed as an artist invested in the dissection of grand subjects and complex systems,” as Jennifer Krasinski wrote in her 2018 review of his exhibition Take My Breath Away at the Guggenheim. But Krasinski puts forward an independent, clear-eyed opinion that slices through all that hype. “Vo’s oeuvre, alas, falls squarely into a contemporary genre we might call conceptually art—work that hypothetically embraces art’s critical function while always deferring to the hand that feeds it.”

• • •

MELISSA ANDERSON ON BABYLON

Spike Jonze (center foreground) as Otto Von Strassberger, Lukas Haas (center right) as George Munn, and Robert Clendenin (back right) as Otto’s Assistant Director in Babylon. Courtesy Paramount Pictures. Photo: Scott Garfield.

The stakes were high for 4Columns film editor Melissa Anderson in her smackdown of Damien Chazelle’s Babylon last year, a film she charges with hastening the demise of cinema even while pretending to craft an epic love letter to that already imperiled art form. “The most incontinent film of the year . . . Babylon belongs to a genre we might call the hysterical historical,” Anderson writes, much of it playing “like a parlor game designed to flatter the TCM devotee.”

• • •

GEETA DAYAL ON THE VELVET UNDERGROUND

Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Lou Reed, from archival photography from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

So far we’ve seen how the bad review can function to lay bare moral and ethical complexities surrounding an artwork, pop the specious balloons of critical fandom, and make a case for a work’s pernicious effect on contemporary culture. As our music critic Geeta Dayal demonstrates in her review of Todd Haynes’s The Velvet Underground documentary, the bad review can also offer the chance to make historical correctives, to balance out the artist’s or work’s (implicit) biases. For Dayal, Haynes’s narrow choice of interview subjects led to factual inaccuracies and group-think opinions; just as problematically, “everyone featured in the film is white.” The movie’s “hazy maelstrom of dreamlike imagery can be reductive to those so often reduced.”

• • •

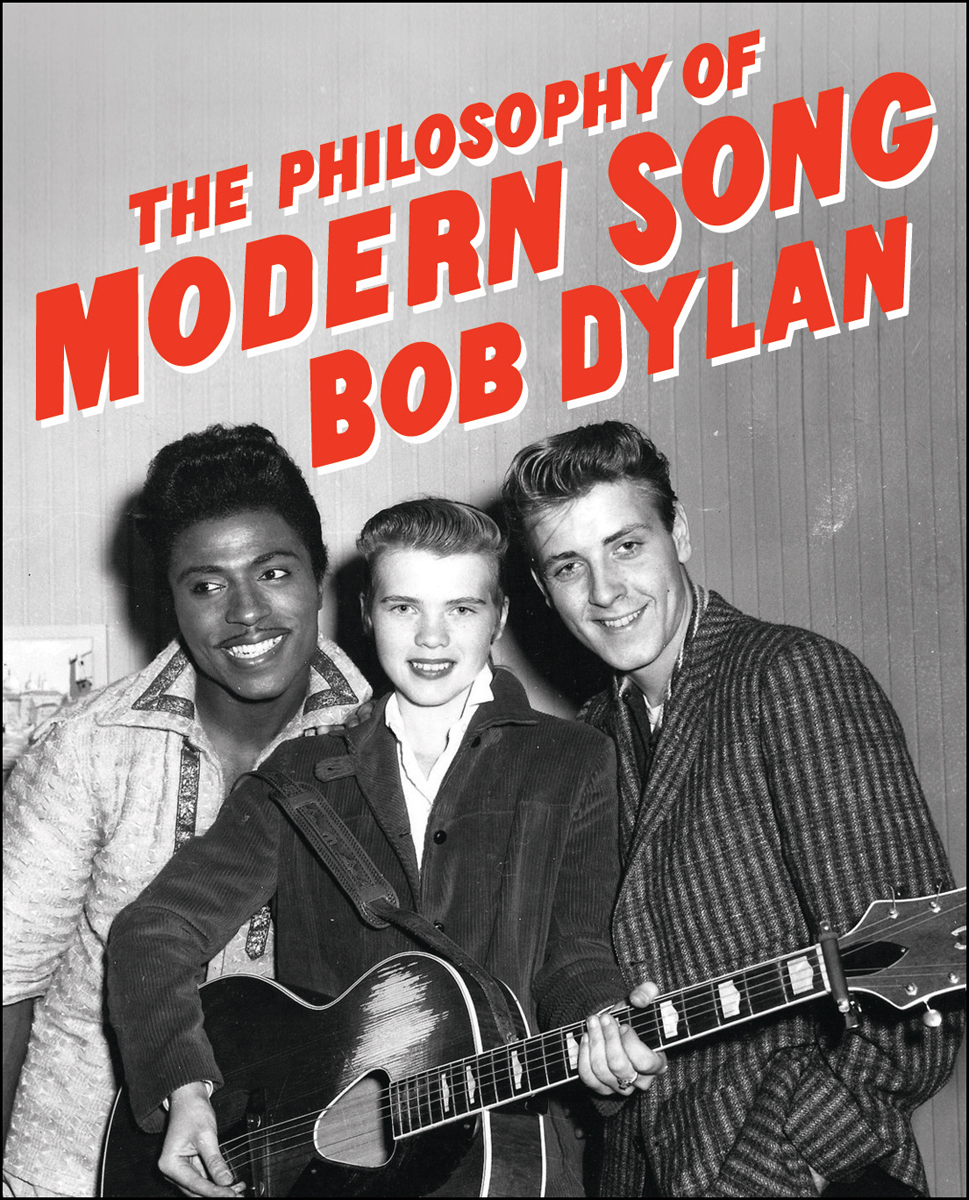

SASHA FRERE-JONES ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF MODERN SONG

Sometimes, the author of a bad review can also be a serious fan of the subject they’re blasting. Such was the case for Sasha Frere-Jones when he scorched Bob Dylan in a piece on the singer’s recently published book, The Philosophy of Modern Song. Frere-Jones’s love for Dylan comes through in his review—but so does his love for music criticism as a form. And while he admires how the book “engages in criticism freely and of its own accord,” he has no patience for the singer’s many critical failures: “Dylan seems generally allergic to describing how things sound,” Frere-Jones observes. “This is a book about lyrics, when it’s about the songs at all. . . . [but] I wish I had learned something about lyrics from this book.”

• • •

BRANDON TAYLOR ON THE UNFOLDING

A breakup note is painful, of course—but when it’s written to someone else, it can also be an excellent and thrilling read. Such is the case with our last bad review in this roundup: Brandon Taylor’s acidic commentary on A. M. Homes’s novel The Unfolding, a book he deemed “depressingly shallow, arriving too late and with too little intelligence, humor, wit, or insight to be useful or entertaining.” Taylor’s trenchant, pulls-no-punches criticism made for such a compelling piece of writing, celebrities like Roxane Gay shared the review online, while Lit Hub included it in their compilation of “The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2022.”

Enervated by so much negativity in one place? Never fear—next week we offer a diametric remedy with a reading list of critical love letters.