4 Columns

4 Columns

The sensual frisson of the human-animal encounter snaps and sparks throughout the 4Columns archives. This week, for our last missive of the summer, we undertake an exploration of these interspecies entanglements.

Is this the gaze of a dog in love?

What motivates the human’s electric desire for the animal? Is it the solitude of the Homo sapiens, self-segregated from nature, that makes her pant after other subjects of the Kingdom Animalia—a lonely need to bridge the conceptual difference between her and other species? Perhaps it’s because we humans cannot fathom animal sentience that we so long to know it; stymied in our understanding, we want to befriend the animal, caress the animal, possess the animal, and often kill the animal, in that ecstatic way humans have of destroying the things we want, so that we can consume them. And so we become enmeshed in a confused and sometimes violent love.

As we humans project all sorts of anthropomorphizing narratives and intentions upon the animals around us, though, the animals simply look back at us blithely. If domesticated, they may well be happy to take whatever we may offer them (food, comfort, shelter), but tend to do so with an opportunistic indifference, even as they wag their little tails to charm us. Maybe this indifference fuels our desire even further. Do you love me back? the human wonders. Please, please love me back. We know animals do release oxytocin, the love hormone, when they are shown the image of their human partners. But to what extent do humans charge the animal imagination, gambol meaningfully in its dreams? To what degree is the human merely incidental to an animal’s unspoken inner life?

Our earliest cultural expressions were representations of animals—magical images meant to draw them closer to us. Today, when we write books about our dogs, or make films about our donkeys, are we trying to conjure a similar magic, to bring them nearer to our hearts? In looking at our animal-centric works of art, what can we learn about interspecies feeling?

Michel Subor in L’intrus. Courtesy Metrograph.

Claire Denis’s 2004 film L’intrus, reviewed in our pages by Erika Balsom early this year, could be one starting point into this inquiry. It’s hard to delineate the plot of this baffling, slippery film, which Balsom deems Denis’s most peculiar and most challenging. We do know it’s a sort of experimental adaptation of a short book by French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy recounting his experience of a heart transplant and subsequent treatment for cancer. Interestingly, in a 2007 discussion with Denis about the film, out of all her departures from his text, Nancy was most intrigued by Denis’s introduction of the dog to his story. In L’intrus dogs become inscrutably important; the film’s characters lay with them sensually, run fingers through their fur, love them, betray them, race them across the snow. Nancy was obsessed with these dogs to the point of writing about them in a short essay after the film’s release, in which he described these canine companions as the site where nature and strangeness meet. The dogs radiate a purity of emotion and love, Nancy muses, but also, with their bark, signal the encroachment of the stranger, strangeness, the unknown—their bark alerts us to those instances of “boundary violation,” as Balsom calls them, that enigmatically structure the film. In her words: “Human and animal, past and present, life and death, dreams and waking life: in L’intrus, every threshold is there to be crossed.”

Ricardo Meneses as Sérgio in O Fantasma. Courtesy Strand Releasing.

The dog figures prominently, too, in João Pedro Rodrigues’s 2000 film O Fantasma. Here, though, human-canine proximity becomes quasi-erotic, all-consuming, and “boundary-violating” in an even more intense way—there is a desire not just to touch dog, but to become dog, as Shiv Kotecha notes in his essay on the film. “The shock and awe of having a human body in an animal world is a central preoccupation for Rodrigues,” Kotecha writes, but especially so in this, the director’s debut feature. The movie centers on “Sérgio (Ricardo Meneses), a kinky, queer garbageman who, despite being conventionally hot and having a tireless sex life, still suffers heartache.” His interactions with others, human or animal, are feral and nonverbal; his preferred frequencies are canine: “Licking, sniffing, or rubbing signals the beefcake’s arousal, and he directs predatory stares at those he wishes to bed. But when he’s alone with Lorde, the sanitation service’s resident hound, Sérgio relaxes, mirroring the pup’s carefree movements.” And by the film’s end, he seems to fully inhabit the position of dog: at a landfill, Sergio “gets on all fours to gnaw at bags and the scraps inside, hunts a rabbit for game, and defecates inside the facility’s central building.” “Tilting ever closer to climate catastrophe,” Kotecha wonders, will we all have to become more animal, like Sérgio, in order to survive?

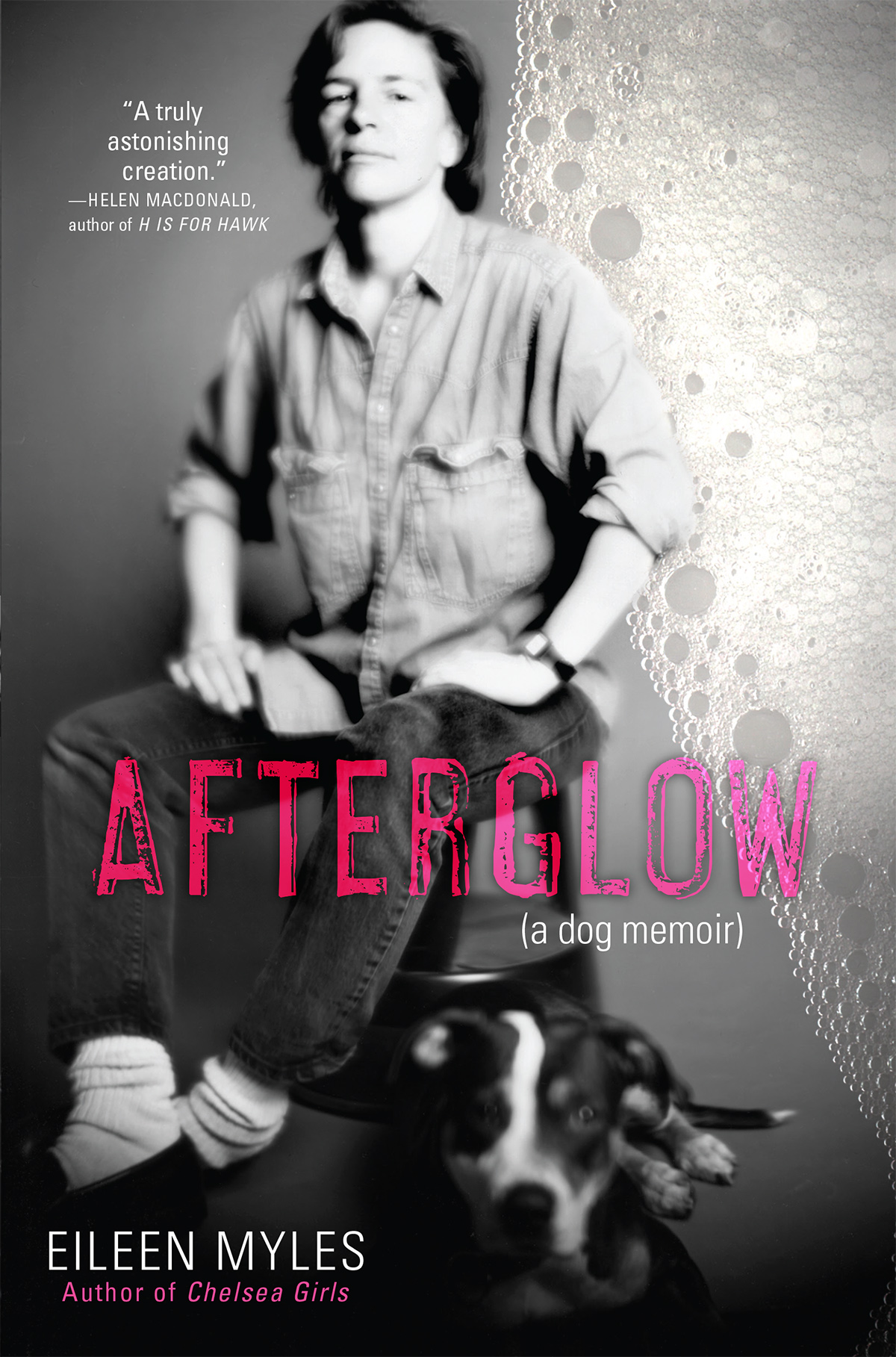

The intensity of the human-dog relationship is also the subject of Eileen Myles’s Afterglow (a dog memoir), an account of “the death and afterlife of the author’s beloved pit bull, Rosie,” reviewed for 4Columns by Moyra Davey. It is a work of mourning, she writes; one that is moiling, laced with absurdity, often puzzling, but “ultimately worth it.” Myles describes their love for and devotion to this dog with an intensity that Davey calls “beyond reason”; through Rosie, Myles tries to mine what dog is and what dog means. “It is revealed that dog is god,” Davey explains; in addition, Myles’s father is reincarnated as Rosie. Unusually for the dog-appreciation genre, mawkish sentimentality is refused. “Darwin, Trotsky, Woolf, Roland Barthes, Jean-Luc Godard (and why not Freud while we’re at it, all pained looks in those home movies except when he’s with his chows) adhere to some notion that only the dog offers unconditional love. This view is not upheld in Afterglow: early in the book, Myles’s relationship to Rosie is characterized as ‘part discomfort & humiliation and part devotion.’ ”

A sort of debasement continues in the relations between humans and other fauna in Kathryn Scanlan’s feral and rigorous 2020 short-story collection, The Dominant Animal. The very writing of the book was propelled by Scanlan’s own tortured minding of various beasts, reviewer Jeremy Lybarger explains. Scanlan, suffering from writer’s block, had “concocted her own DIY artist residency. She found a place on Airbnb—a wreck in the desert—where she could stay for free if she agreed to tend the homeowner’s animals. ‘One of the woman’s dogs would attack the chickens and steal the eggs, so I had to keep him away from them,’ Scanlan recalled . . . ‘The goats were small but really volatile. They would buck and butt me with their heads and try to stomp my dog.’ ” This oddly hostile atmosphere of interspecies tension pervades the resulting collection, Lybarger writes, much of which features “a menagerie of (mostly domesticated) animals.” Somewhat like in O Fantasma, these creatures seem to penetrate their human counterparts; descriptions of the animals and their doings appear “along with a catalog of the body’s bestial processes: eating, fucking, shitting.”

Eugène Delacroix, Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother, 1830. Oil on canvas, 130 × 195 centimeters. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux.

But we also find animal love in our archives, such as in Amy Sillman’s review of a major Delacroix retrospective at the Met in 2018. “Delacroix made the picture plane something ‘bloody and animal and hot,’ to quote art historian T. J. Clark,” Sillman enthuses; the “work emerges from this kind of meat and motion . . . Delacroix’s world is one of jarring transitions and negative dialectics, where humans are indistinguishable from animals.” There is a sincere adoration in his energetic and wild and tender portraits of these beings, such as one painting singled out by Sillman, Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother, with its strange and implausible detail of the young wild cat’s marvelously massive hind paws pressed up against the picture plane, as if against a glass.

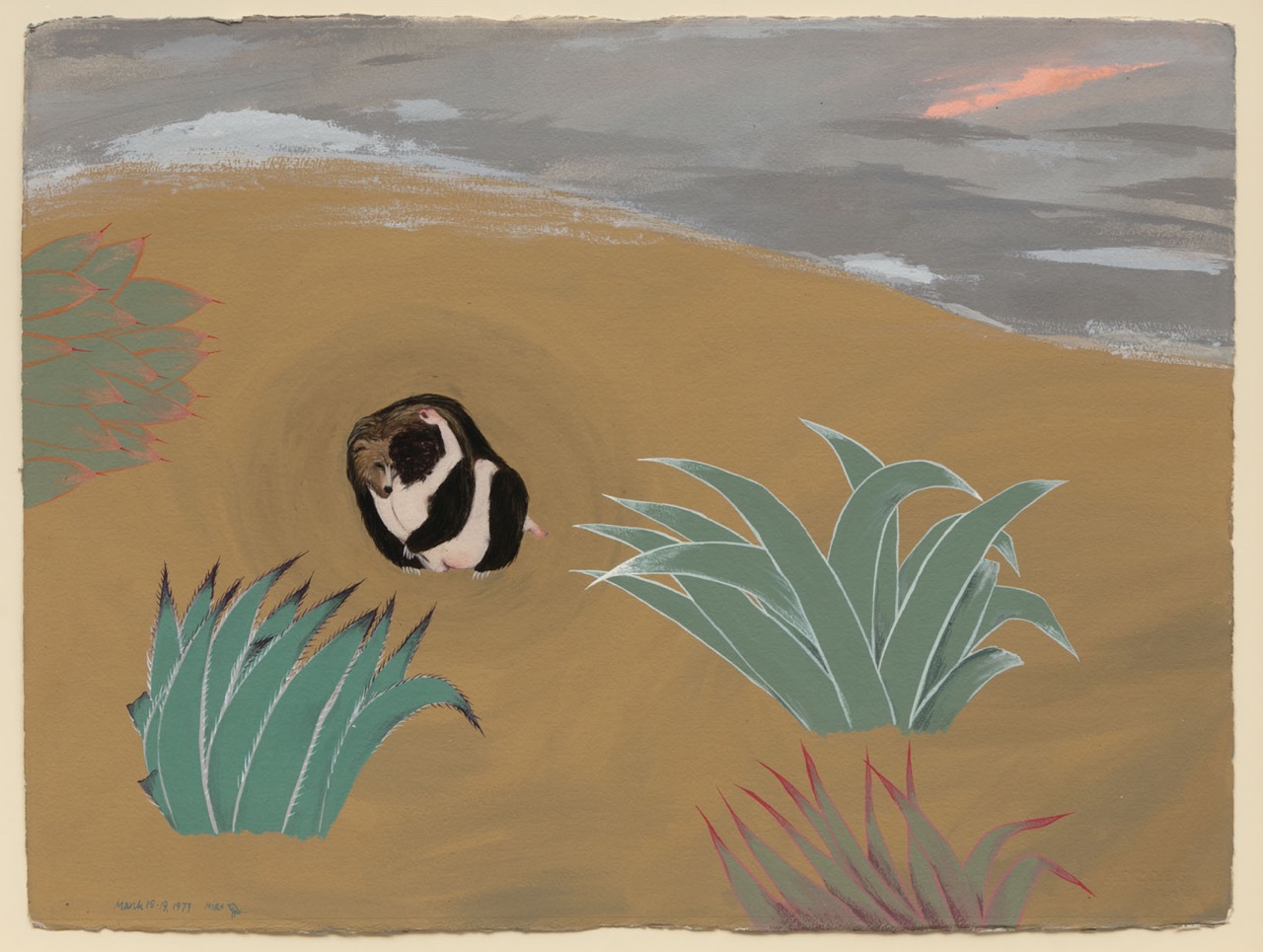

Mira Schor, Bear Triptych (Part III), 1973. Gouache on Arches paper, 22 × 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

Interspecies love also glows in the work of another artist who has appeared in our pages: Mira Schor, whose 2019 exhibition of early paintings at Lyles & King was reviewed by Johanna Fateman. But here, the theme appears in a more lascivious light. The “heart-quickening high point in the intriguing exhibition,” Fateman writes, was an “eerie, erotic” series that raises the stakes of the human-animal encounter to a dizzying high. In the first panel of Bear Triptych (1972–73), Schor paints herself, nude, gazing into the eyes of a grizzly bear as they share a tentative embrace; by the last panel, “the artist and animal [are] locked together, having sex.”

Gunda. Courtesy Neon.

If an artist may mythologize human-bear sex, does the bear have any say in it? Might a bear know a carnal desire for a human? All of the films, books, and paintings discussed so far have, as they must—for no other way is possible—been constructed from the human’s point of view. But we conclude our journey into interspecies relations with a movie that aspires, to the extent that it can, to capture what the animal might be thinking: Gunda, directed by Victor Kossakovsky and reviewed by 4Columns film editor Melissa Anderson. To right the imbalance of the human’s false sense of superiority to the animal, Anderson writes, Kossakovsky “keeps his cameras near to the ground, approximating the POV of his film’s subjects: the sow of the title and her litter of piglets, and, given lesser screen time, a flock of chickens and a herd of cows. For ninety minutes, we are immersed in the activities of these farm fauna. No humans appear in the film.” For Anderson, Gunda “takes up the question posed by John Berger in his still-influential 1977 essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’ At its most fundamental level, [the film] underscores one of the essential truths laid out by Berger in his treatise: ‘Animals are born, are sentient and are mortal.’ ” Without ever resorting to anthropomorphizing, bathos, or reducing its subjects to cuteness, Kossakovsky’s sensitive and beautiful documentary captures the animals regarding us with penetrating eyes that may make us human viewers feel all sorts of complicated ways—but that also lets us feel, finally, connected.