4 Columns

4 Columns

4Columns will be back with a new issue September 3. This week, we devote ourselves to literature in English translation, and grapple with the failures and fecundities of carrying one language into another.

A few of the titles in translation that reside in the managing editor’s living room.

To read a work in translation is not just to “learn” about “other cultures”—it’s an exercise in differently knowing experience itself.

For instance: in the Andean language Aymara, the English phrase “last year” would be translated as nayra mara, or “front year,” and “next year” as qhipa marana, or “back year.” The future is not ahead of you, like in English—you’re always facing your past, instead, and constantly moving toward it. How to translate “yesterday” from one of these languages to another; how to read your way into a spatial conception of time reversed from your own?

Or a different case: in Polish there is no exact equivalent for the English word grief. Some linguists believe that is because grief is so commonplace, so general in the existence of the Pole, that there is no need for a special word for it—grief is just another wave in a vast ocean of sadness. How to translate a feeling for which there is no term? How does the Polish speaker feel when she reads about it through approximation (the sweeping sadness of żałoba, the wrenching anguish of boleść, none of them precisely the same)? Can she still know the sensation of a heart being clawed, of a black inky poison in the stomach?

Or yet another problem: “PUNCTUATION IS COLONIAL!” a writer declared when his editor on the Mada Masr news desk—Ania Szremski, now the managing editor at 4Columns—suggested sundering his text, translated from Arabic into English, with commas. The writer’s objection to imposing the cold hard dividing pauses of an imperialist grammar onto his diffusing prose was just one of the many conceptual eddies into which translation would throw the bilingual team of journalists and editors at the publication.

Readers may not be privy to or care at all about these dilemmas, but the decision to add those colonial commas or not would create such substantially different linguistic terrains—in terms of sensuousness, clarity or ambiguity, offering of meaning. Choices like these are all part of the dolor and the rapture of literary translation: how its compromises can build and undo our worlds. We’ve gathered here a list of ten 4Columns book reviews that grapple with the thrills and disappointments of the contested act of translation—including one that brings forth the voice of the translator herself.

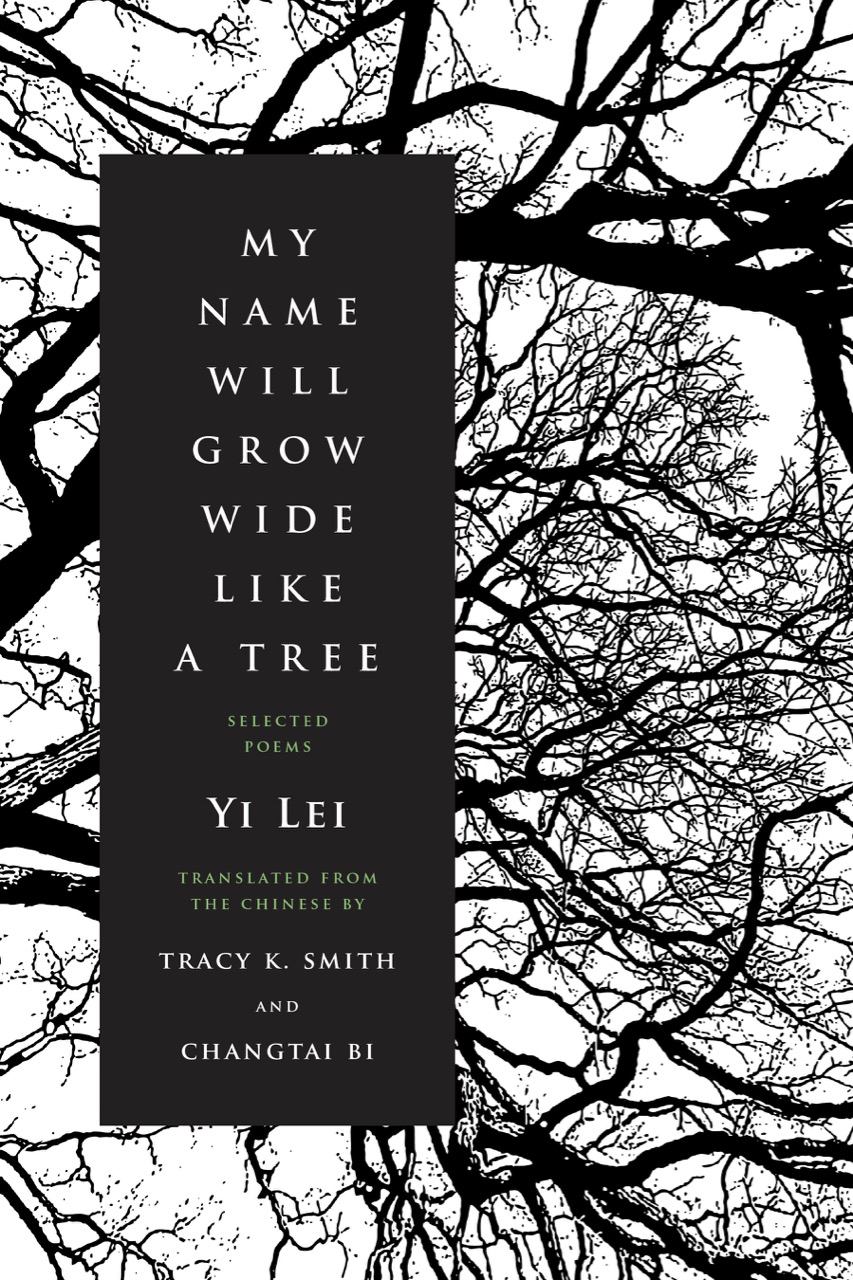

(1)

My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, by Yi Lei, translated by

Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi

Reviewed by Andrew Chan

We begin with a work whose beautiful ambition was marred by presumption. Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi’s translation of Chinese author Yi Lei’s poetry, published in 2020 as My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, certainly does a service by introducing Anglophone readers to Yi Lei via the “undeniably supple musicality” of Smith’s delivery, writes reviewer Andrew Chan. But the ever-fraught problem of translation looms large here, especially for those readers, like Chan, who are proficient enough in English and Mandarin “to recognize the glaring chasms in style, tone, and content” between the original poems and “these willfully unfaithful renditions.” “There exists an understandable but faulty assumption that certain languages are so distant from one another that translation requires a high degree of artistic license,” Chan says. “But words still mean what they do.”

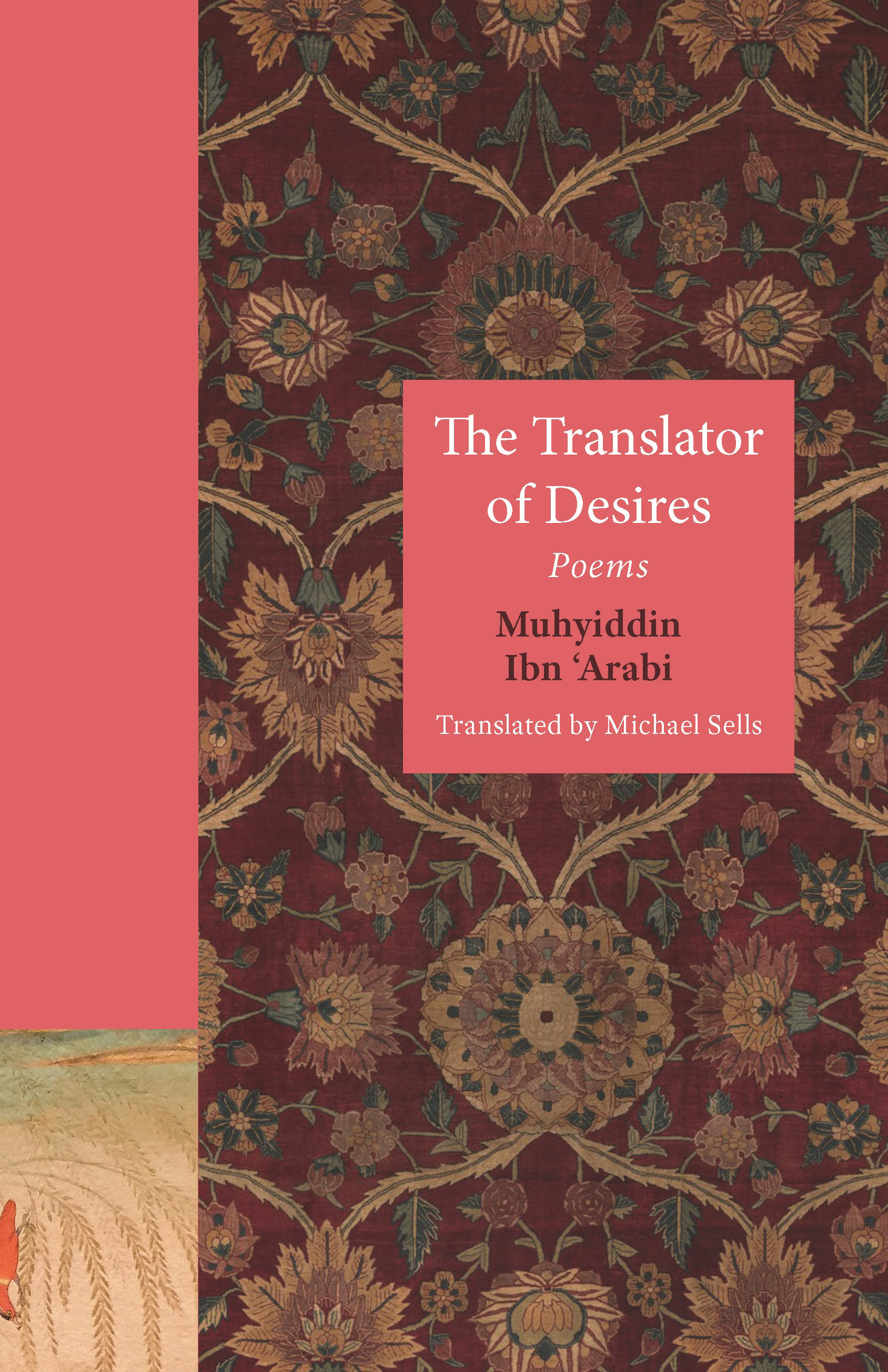

(2)

The Translator of Desires, by Ibn ‘Arabi, translated by Michael Sells

Reviewed by Omar Berrada

Now for another volume of poetry whose English version takes some decisive departures from the source text—but this time to glorious effect, each considered choice reading like a tender act of care. Michael Sells’s The Translator of Desires—the first complete English translation of Sufi mystic Ibn ‘Arabi’s thirteenth-century sequence of love poems to be published in over one hundred years—shimmers with music, euphonic concision, mystical meaning, and the knowledge born of decades of research, reviewer Omar Berrada opines. This new unfolding of Ibn ‘Arabi’s eloquent ardor, “the first-ever Arabic volume in the Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation,” is an exemplar of the rich and beautiful work that can be produced by a translator whose practice reaches “beyond itself,” “bringing together research, pedagogy, spirituality, and poetry.”

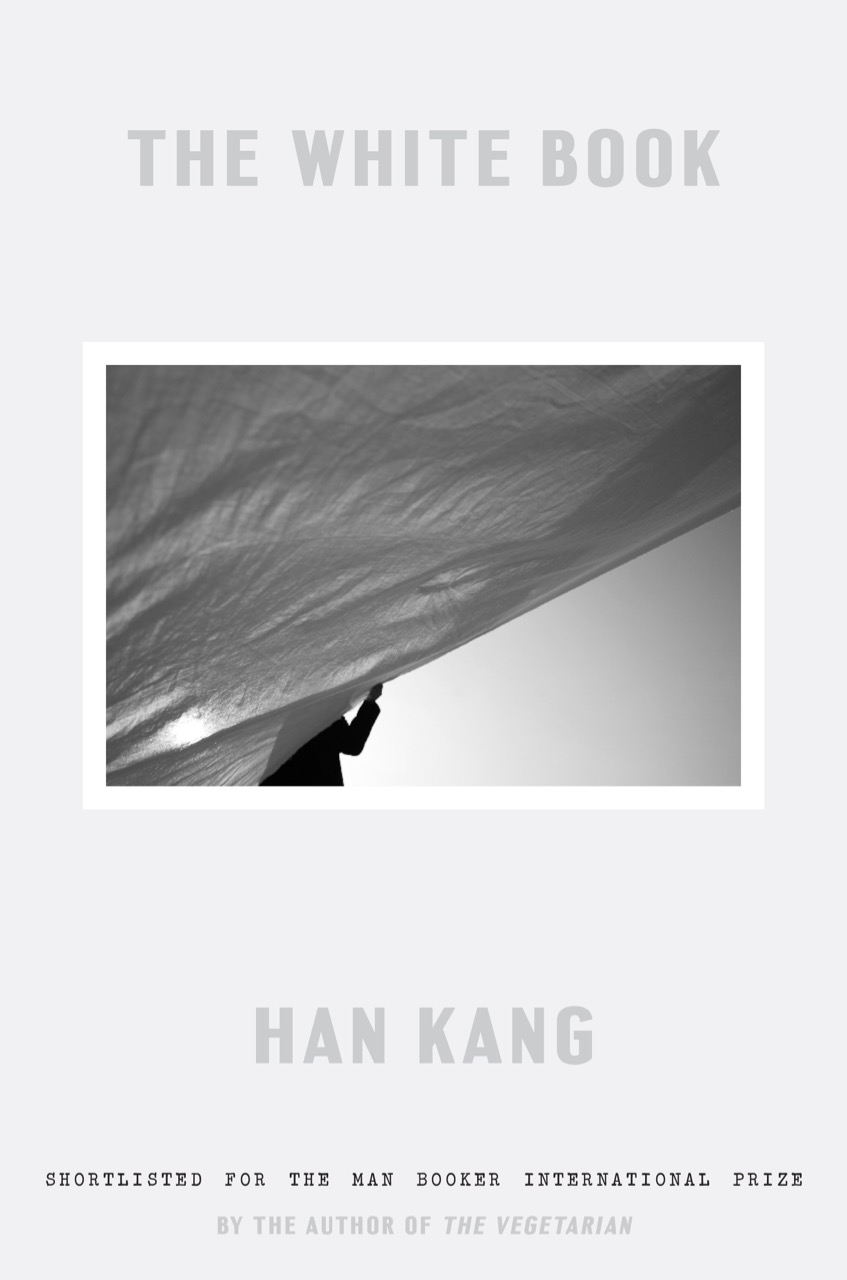

(3)

The White Book, by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

Reviewed by Sowon Kwon

In his review above, Chan cites Deborah Smith’s translations of the Korean novelist Han Kang, “which some bilingual critics have deemed cavalierly loose.” Sowon Kwon, however, in her essay on Kang’s The White Book (a poem-like fiction meditating on grief as much as on the color), appreciates the “directness (I would even say a kind of imagist plainspeak), economy, and phrasal cadences” of Smith’s work, which Kwon feels “has captured much.” Still, certain things are inevitably elided in translation, such as the nuances of the word “white” itself: “Also lost, but possibly inferred, is the connotative nuance in 흰 hin, as opposed to the synonymous 하얀 hayan, which Han has described as a white that is ‘cotton-candy clean.’ . . . In hin is a ‘certain sadness, the color of fate.’ It is double-edged, a white in which life and death are entwined.”

(4)

The Magnetic Fields, by André Breton and Philippe Soupault, translated by Charlotte Mandell

Reviewed by Mark Polizzotti

The founding text of the Surrealist movement, André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s The Magnetic Fields, is a real Gordian knot for translators. Breton intended the work to be as close as possible to “spoken thought,” and reviewer Mark Polizzotti, himself a translator, warns that these torrential prose poems offer up “challenges that stud these particular fields with more than the usual landmines.” A new translation by Charlotte Mandell, published last year by New York Review Books, admirably avoids many of the pitfalls—but also tumbles headlong into others, Polizzotti laments. Though an improvement from the last, fussy translation of the work by David Gascoyne in 1985, Mandell’s version suffers from an overabundance of fidelity to the source material, yielding “a text that reads like a deliberate translation, rather than like brilliantly unfettered ramblings. . . . What’s too often missing is the tone, the aura, that gives the text its peculiar tang; the verve and manic energy that, in French, sound like two excitable young men scribbling as fast as their pens will carry them.”

(5)

Anniversaries, by Uwe Johnson, translated by Damion Searls

Reviewed by Charity Scribner

When New York Review Books published Damion Searls’s translation of Uwe Johnson’s massive novel Anniversaries, it was something of a landmark literary event—at least for those keen on twentieth-century European literature. “Many consider . . . Anniversaries to be the most important German novel of the postwar period,” writes Charity Scribner. “To date, it has not gone out of print. . . . [It] surpasses contemporary experiments in autofiction. Karl Ove Knausgaard probably read Anniversaries before writing the six books of My Struggle. Rachel Cusk would have much to learn from it now.” But, amazingly, until Searls’s heroic undertaking, the full work had never been available in English. Its first translation in the 1970s omitted “substantial portions of the text . . . the deletions removed crucial contexts of German history and thinking,” Scribner explains. Searls’s complete restoration of Anniversaries encourages us today to “reconsider the stakes of literary fiction within our current political conditions.”

(6)

The Impudent Ones, by Marguerite Duras, translated by Kelsey L. Haskett

Reviewed by Jeanine Herman

When Marguerite Duras was twenty-six, she wrote her first novel: Les impudents, published in 1943. Duras would later dismiss it as “very bad,” and it was never published in English, even after the rapturous success of her late masterpiece The Lover, a book that seduced scores of Anglophone readers, leaving them wanting ever more. Luckily, earlier this year, the New Press published the very first English translation of Les impudents, by Kelsey L. Haskett, a “well-cadenced” effort, according to our critic (and renowned translator herself) Jeanine Herman. Haskett’s text allows us to access a very different Duras from the one most of us know: “this is not at all a new novel in the sense of the nouveau roman, with its spare and elegant, almost Zen aesthetic, but very much an old novel—an old-fashioned novel with fairly conventional language.” Instead of the “minimalist, brutal, incisive” Duras of The Lover, in The Impudent Ones we find a young author who is “maximalist to the max . . . before the economy of style came the excess,” Herman writes, “an excess born of romanticism.” But that doesn’t mean it’s a bad book, like Duras believed! In fact, it’s rather a “remarkable first novel,” and its translation grants international readers more penetrating insight into the entirety of Duras herself.

(7)

Whereabouts, by Jhumpa Lahiri, translated by Jhumpa Lahiri

Reviewed by Hermione Hoby

Translation gets self-reflexive (perhaps downright self-interested) in Whereabouts, published in early 2021, by American author Jhumpa Lahiri. In recent years, Lahiri has abandoned her earlier, sharply observed fictions of “immigrant experience” in favor of writing in and about a newly learned tongue, Italian. She then renders these Italian texts back into English, making this process a sort of doubled self-translation. Our critic Hermione Hoby wonders what this feat of bilingualism really serves, though, beyond the author’s own satisfactions. Lahiri’s self-translating process “doesn’t lend the book any palpable, particular joys,” Hoby says. “One can admire the Herculean effort, but the shared delight in learning is missing.”

(8)

Memoirs of a Polar Bear, by Yoko Tawada, translated by Susan Bernofsky

Reviewed by Megan Milks

Like Lahiri, novelist Yoko Tawada often translates her own writing. Tawada’s practice is not a cool academic exercise in linguistic athleticism, however, but rather one that “adopts bilingual perspectives to unsettle her readers’ relationships to language, culture, and national identity,” writes Megan Milks in their review of Memoirs of a Polar Bear, Tawada’s sixth work to be made available in English (it was published in the US in 2016). “It was written first in Japanese, then translated into German by Tawada herself,” Milks explains, and now has been “translated from German to English by Susan Bernofsky.” Nothing feels lost amid so much trans-lingualism—indeed, Bernofsky’s English version “maintains Tawada’s reliable brilliance; the novel practically gloats with originality,” Milks relates. These issues of translation are particularly pressing here because “in Tawada, language selection is never unconsidered,” whether on the part of the author or her polar bear protagonist. The bear, who would like to write her memoirs, is urged by her human publisher to write in her “mother tongue,” but, having resided almost all her life in captivity, she has forgotten what it was—and so, like Tawada (as well as Kafka, yet another bilingual author, whose animal parables play an important role in this book), the furry beast endeavors to write in German. Here as throughout her oeuvre, Tawada roundly refuses the primacy of the “native language.”

(9)

Hurricane Season, by Fernanda Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes

Reviewed by Eric Banks

As we saw in Polizzotti’s remarks on Mandell’s The Magnetic Fields, for the literary translator, capturing voice is just as crucial as transferring meaning. A fantastically successful example of managing to convey the particular angles of an author’s singular style is Sophie Hughes’s “vigorous translation,” as per reviewer Eric Banks, of Mexican writer Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season, published by New Directions last year. “Each chapter is composed of a single uninterrupted paragraph, all of them comprising the author’s teeteringly long, clause-atop-clause sentences,” Banks explains. “The stylistic effect, in [English translation], is remarkable and peculiar.”

(10)

This Little Art, by Kate Briggs

Reviewed by Ben Ratliff

“While reading a book in translation, especially a fairly recent one, at the point of full engagement I become aware of two minds at once. I am not just reading the author; I’m reading the translator reading the author.” So begins Ben Ratliff’s review of This Little Art, in which we finally get the point of view of this meta-reader hovering at the periphery of the reader’s vision: the translator herself, in this case, Kate Briggs. Published by Fitzcarraldo in 2018, “This Little Art is a non-straightforward critical book about the nature, necessity, and stakes of translation. For Briggs, translation means a great deal: communication, desire, restorative justice, a basic act of caring. . . . In a way, the book is a continuous redefinition of translation, with the stakes growing ever higher. You think the translator’s job is utilitarian? Briggs has news for you: it is like raising a child.”