4 Columns

4 Columns

In the heat of the sweatiest season, a slew of mystery and suspense books to make your blood run cold.

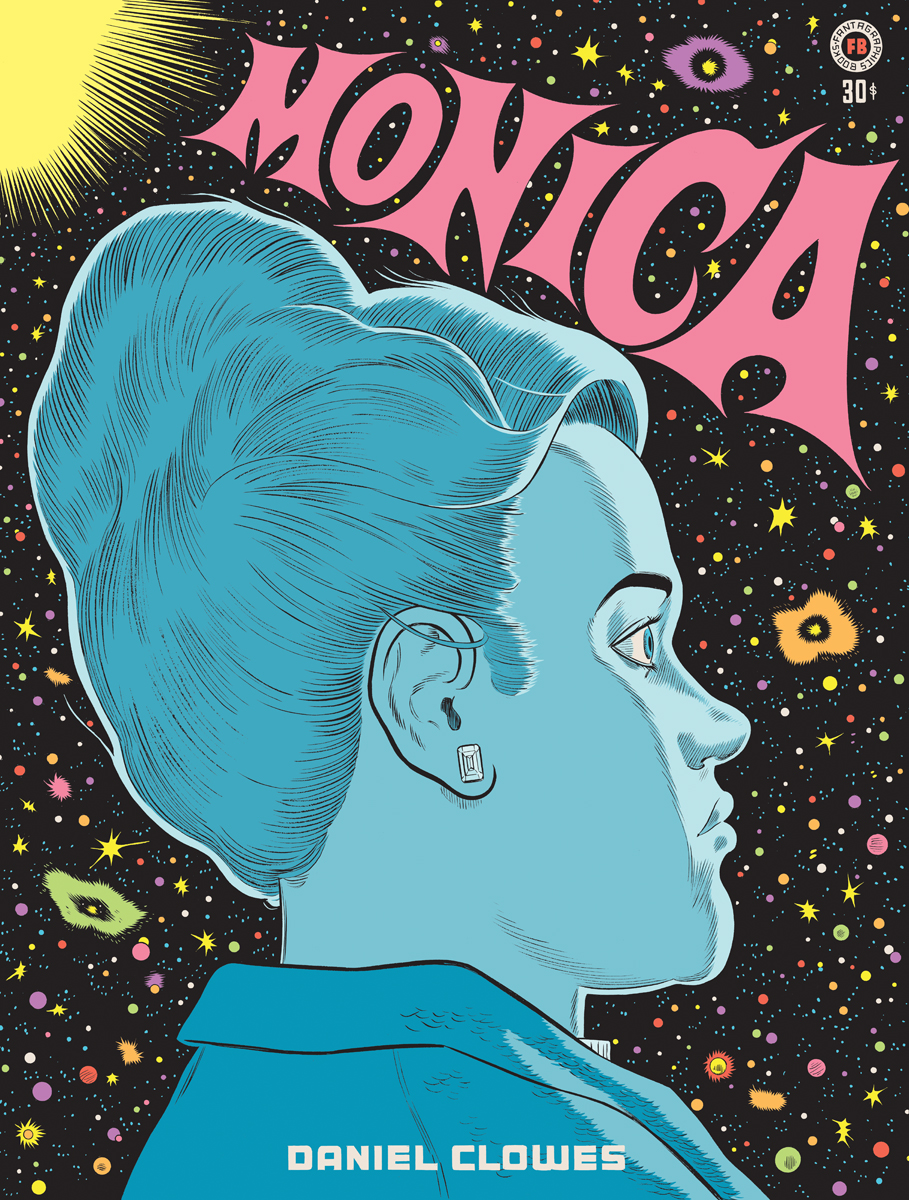

From Monica, by Daniel Clowes. Courtesy Fantagraphics.

It’s a known fact that when the temperature climbs, so does the crime. As the world swelters this climate-change summer, we indulge our more delinquent tendencies with novels of murder, mayhem, mischief, girls gone missing, and all the other makings of a good thriller. As the city nights pulse with steamy menace, steel yourself with this selection of ten of our most gripping reviews (in no particular order) of books that directly inhabit the thriller-mystery genre, evoke it in sophisticated ways, or blur its boundaries altogether.

• • •

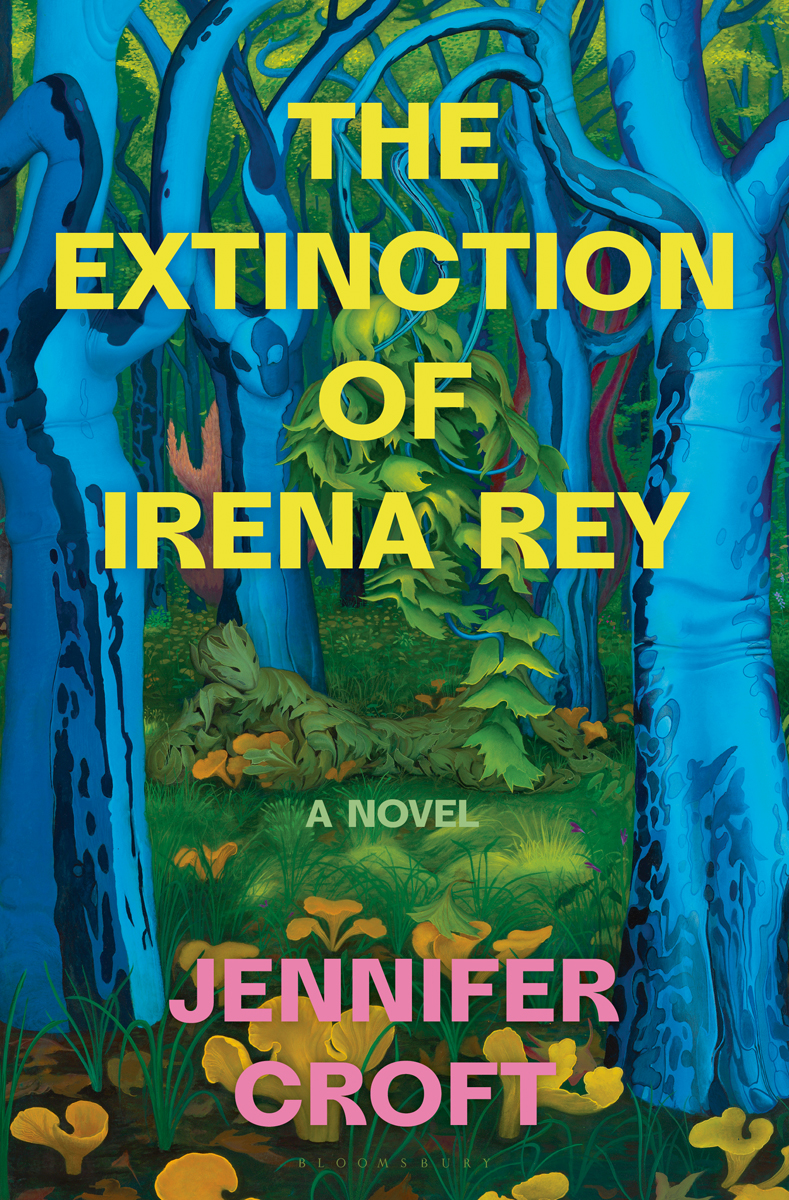

ANIA SZREMSKI ON THE EXTINCTION OF IRENA REY

A coven of translators meets in the Polish primeval forest, only to find their beloved author is missing . . . Jennifer Croft’s new novel, The Extinction of Irena Rey, published earlier this year, is rife with poisonous serpents, possible murders, mysterious bloodthirsty archers on horseback, and all the nefarious treacheries of language (especially English). And yet, it’s also more than the sum of those parts. In her review, 4Columns senior editor Ania Szremski writes, “As much as this novel is at once a truly fun-to-read genre mash-up (mystery, murder, romance, taxonomy of marvelous rare mushrooms), a story of the cult of genius and the literary market, and a contemplation of the complex act of translation, its inquiry penetrates to the very heart of why we write, and how that may be inseparable from how we live, and are killing ourselves, on this planet.”

• • •

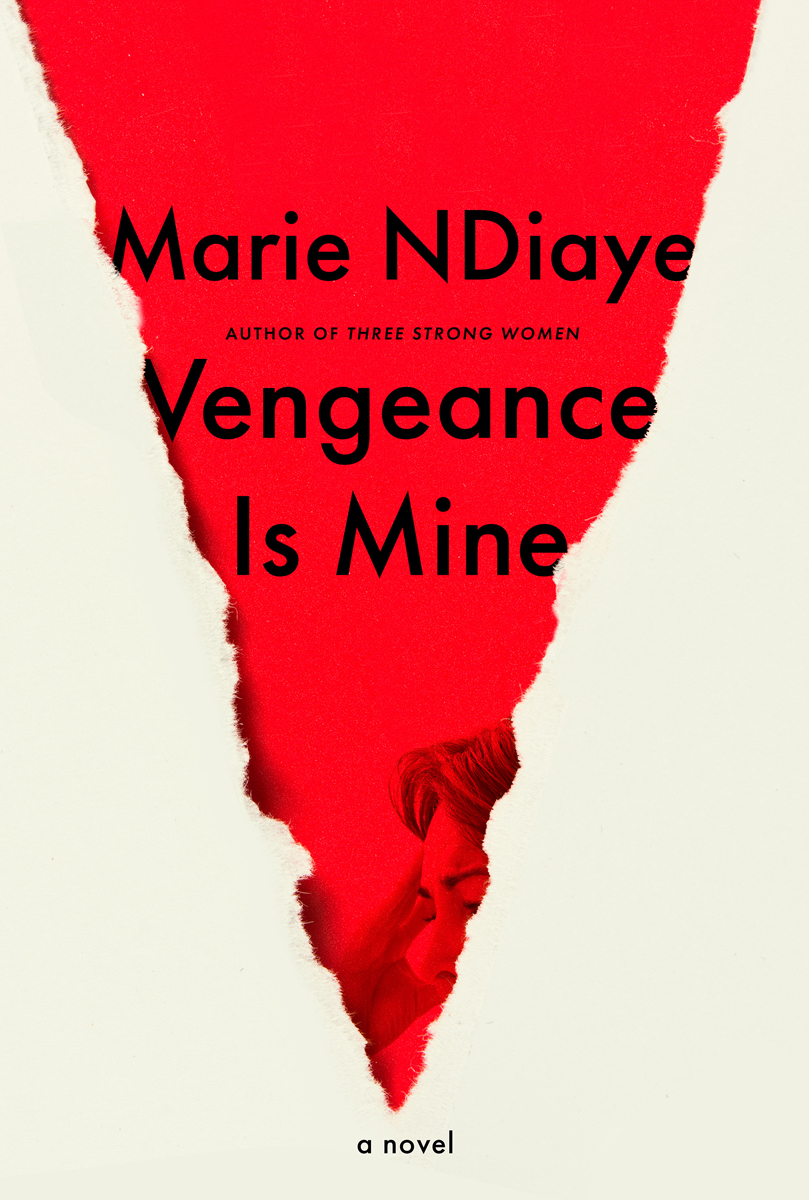

HERMIONE HOBY ON VENGEANCE IS MINE

Hermione Hoby is a true, completist aficionado of French Senegalese novelist Marie NDiaye, and in her review of NDiaye’s latest, Vengeance Is Mine, published last year in English translation by Jordan Stump, Hoby asks, “What makes her a master? In part, it’s NDiaye’s deft interweaving of those narrative traits we associate with genre fiction, specifically crime thrillers—suspense, mystery, intrigue, a touch of the supernatural—with a high-modernist sensibility in thrall to the shifting, refractive nature of memory, unsettled selfhood, and intersubjectivity tout court.” And Vengeance Is Mine is a superbly controlled example of NDiaye’s blend of heady high and supposed low into a lucid sophistication: “It wouldn’t be untrue, only inadequate, to call this a crime novel. After all, our protagonist is a lawyer, and the narrative is set in motion by murder.”

• • •

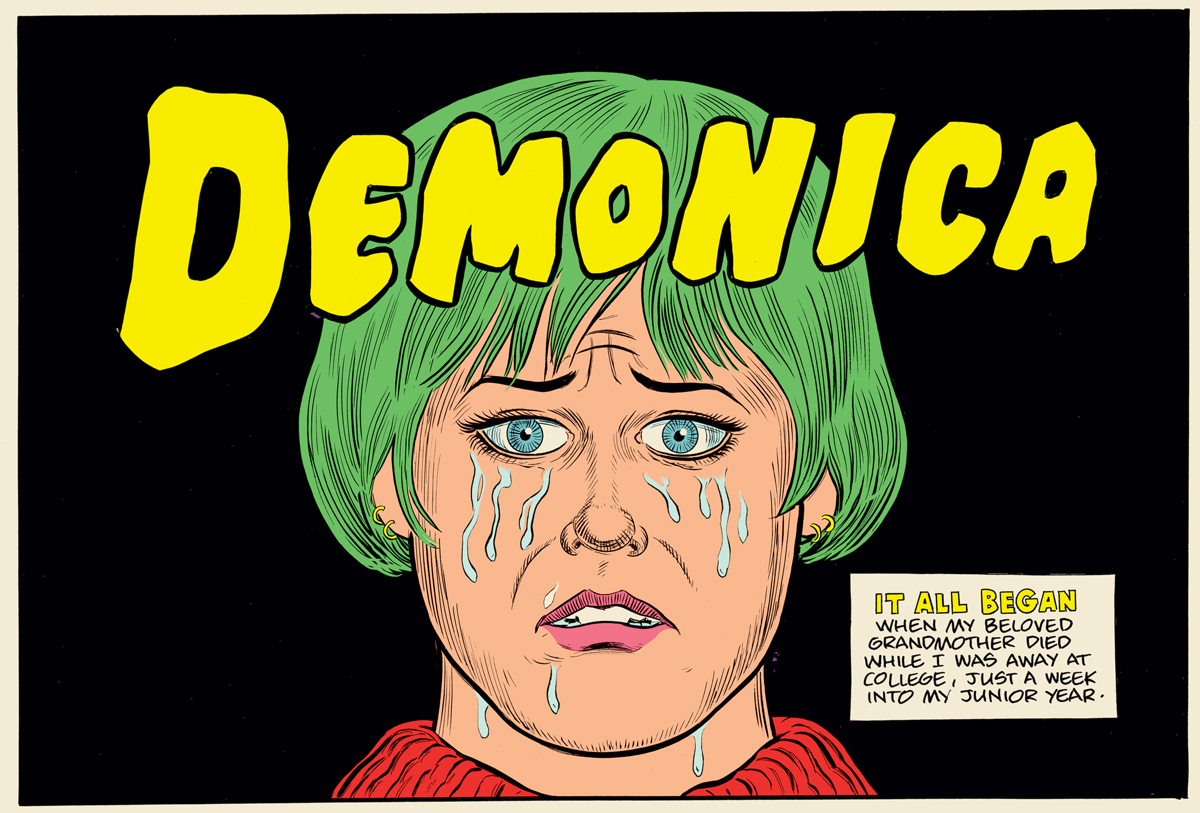

MARK DERY ON MONICA

In post-punk auteur Daniel Clowes’s latest graphic novel, Monica, out last year, gothic Hawthornian horror meets postmodernism, writes reviewer Mark Dery: “In Monica’s cover story, a mystery about a woman desperate to unriddle the miseries of her childhood, Clowes confronts—with his usual black-comedic wit—questions usually reserved for religion. He wrestles with the complications of life after death (what do you do when grandad reveals himself, from beyond the grave, as an anti-Semite?); unearths the historical roots of Gen-X angst and anomie, which for Clowes are the psychic scum left by the receding wave of the counterculture; ponders the perils (and seductions) of blind faith; and takes the full, painful measure of the persistence of memory that makes us prisoners of our pasts.”

• • •

CAL REVELY-CALDER ON THE SHARDS

In The Shards, Bret Easton Ellis’s first new novel in thirteen years, out at the start of 2023, “teenagers start to vanish, then reappear as mutilated corpses, slowly putrescing on tennis courts” in a blend of menace and luxury, Cal Revely-Calder writes in his review for 4Columns. “Framed as the traumatic memory of ‘Bret,’ recalled from the vantage of his adult life, [The Shards] follows a set of privileged high schoolers across two unholy months” as a serial killer called “the Trawler” preys on local girls. “What we have, then, is two sides of a trashy coin,” says Revely-Calder: “Gossip Girl in the ’80s, and skulls impaled on sticks. We’re treated to a slasher horror and a teenage drama, with a mischievous embrace of the cornier aspects of each.”

• • •

ERIC BANKS ON RED MILK

“Written as if it were the opening lines of a crime novel, the scene-setting is a master case of indirection: there is a mystery here, in [the protagonist’s] embrace of the neo-Nazi cause, but it is one that the author will steadfastly refuse to unlock,” writes Eric Banks of Icelandic author Sjón’s imagining of a new villain in Iceland’s past in his slim novel Red Milk, published in early 2022 in English translation by Victoria Cribb. “Sjón’s story examines an otherwise unremarkable and largely featureless character, based loosely on a real-life [man] who died young of cancer . . . a certain Gunnar Pálsson Kempen, a shadowy figure who devotes much of his twenty-four years to organizing a minuscule neo-Nazi movement in his native Iceland as it emerges from World War II.”

• • •

JESSI JEZEWSKA STEVENS ON THE CHEFFE

NDiaye makes our list yet again with Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s review of Stump’s English translation of The Cheffe, a tale of its eponymous character’s unlikely rise to fame in the culinary world. It is, “on its surface, about French cooking and cuisine,” Stevens writes. “But readers should be disabused of any expectation of a simple pleasure trip” in this work, which borrows “from Freud, supernatural thriller, and family saga. . . The way in which the world seems to pick up and rearrange itself, unrecognizable and out of reach, echoes the grammar of a horror film, or else the process of going insane. Reading NDiaye is akin to coming across a previous patient’s psychological assessment on your therapist’s desk; you’re hopelessly drawn in, even as you ought to look away.”

• • •

DAVID O’NEILL ON WHO KILLED MY FATHER

Édouard Louis’s Who Killed My Father, translated into English by Lorin Stein in 2019, may not seem like a thriller of a book. The French wunderkind’s “short, wrenching, tender-hearted essay addressed to his dad,” in the words of reviewer David O’Neill, picks up ideas from Louis’s two prior books: “how societal injustice plays out at ground level, how poverty twists minds and bodies, how the oppressive codes of masculinity hurt everyone, not least the men who most zealously uphold them.” But on the other hand, O’Neill reveals, “In families, as in politics, the question is always: Who is getting revenge on whom? Especially with fathers and sons, the answer is never clear. Like many remembrances of a parent, Who Killed My Father is structured as a mystery story without a plot. The son sees clues everywhere, but they don’t solve anything.”

• • •

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE CASTELLI ON A GIRL IN EXILE

Ismail Kadare, arguably Albania’s most celebrated cultural export, who passed away earlier this month, wrote novels with a profound sense of history and a “poetic realism lightly tinged with satire,” in the words of Jean-Christophe Castelli in his review of A Girl in Exile, first published in 2009, then in English translation by John Hodgson in 2018. It’s “a lovely and melancholy novel,” says Castelli, that “unfolds like a mystery, through successive revelations” driving toward an answer as to why the eponymous character, Linda B., ended her life. The result “is both a timeless, ghostly love story, and a trenchant portrait of the artist in a totalitarian state.”

• • •

DAVID ULIN ON THEMYSTERY.DOC

Matthew McIntosh’s 1,660-page theMystery.doc is very much, as its title would suggest, a mystery—a meta-story of the writing of a mystery novel, a nested story of multiple missing persons, and, finally, a philosophical story of the greatest mystery of all: “the stomach-dropping question of why we are alive,” argues David Ulin in his review for 4Columns. At the same time, says Ulin, “there’s little purpose in trying to summarize the plot . . . Perhaps the most useful way to think about theMystery.doc is as an experiential novel, one we live with (or through), rather than read. A pastiche, a collection of moments that both connect and don’t, it blurs the line between text and image, fact and fiction; it is not postmodern but post-postmodern, or maybe none of the above. At the same time, it is surprisingly accessible for such a long book: not a critique of meaning so much as an evocation of meaning’s aftermath—an expression, in other words, of the chaotic culture in which we live.”

• • •

DAVID O’NEILL ON THE MORNING STAR

“The disquiet starts early in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s new thriller, The Morning Star,” O’Neill wrote upon the book’s 2021 publication in English translation by Martin Aitken. It was Knausgaard’s first novel since his autofiction blockbuster My Struggle, and though that series casts a long shadow over The Morning Star, the aim here is quite different: “the frolic and abandon of genre fiction,” in which Stephen “King-style horror/fantasy is used to make death feel more real.” For fans of this vein of Knausgaard, it transpires that The Morning Star was the first in a trilogy, followed by The Wolves of Eternity—and the last volume of which, The Third Realm, will be out this October. The night of the thriller continues!